(This is the Lesson Plan 2 for Shane Doyle’s curricular unit, “Tribal Oral Traditions and Languages in the Plains Region of the Lewis and Clark Trail.”)

Geography and the Northern Plains Oral Tradition

Lesson Topic: Lewis and Clark’s Map

Grade Band: Grades 9-12

Length of lesson: 60–90 minutes

DESIRED RESULTS

Big Ideas:

The tribes of the Northern Plains maintained vast geographic knowledge of their homelands and shared their knowledge with newcomers to the region.

Lewis and Clark’s original map to travel west was developed largely from information shared to Peter Fidler by Ac-Mo-Mik-Mi of the Blackfoot tribe.

Our knowledge of our regions today is often based upon maps rather than our experience traveling or from oral traditions in our community.

Enduring Understandings:

The geographic knowledge that tribal people maintained about their homelands displayed the strength and reach of their oral traditions.

Lewis and Clark entered a region that tribal people knew extremely well because of their travel, trade, and sharing of land and knowledge.

Sharing and respect are important aspects of tribal culture.

Essential Question(s):

- How does Feathers’ map disprove the idea that tribal people of the Northern Plains knew very little about their region?

- If Feathers’ map showed that there was no northwest water passage, why did the Lewis and Clark Expedition still believe that such a route was possible?

- What is the difference between the written and oral tradition in understanding geography?

- How can we show appreciation and thanks to individuals who have helped us find our way in life?

Place-based Considerations:

The Northern Plains are an area of great movement, where all the tribes moved in a seasonal cycle, trading and interacting with one another throughout the year.

“Honoring Tribal Legacies” is a journey of healing

This lesson is meant to reveal to students the immense knowledge of the land that Plains Indian people had gained from thousands of years of hunting, gathering, and trading on an open landscape. These “people of the land,” as the Apsáalooke (Crow) people refer to other tribal groups, loved their homelands and knew them better than anyone. They shared and interacted frequently with their neighbors and sustained trading partnerships for many generations before the Lewis and Clark Expedition entered their homelands. When students learn a more complete picture of the tribes, stereotypes and misunderstandings are addressed and tribal culture is respected, allowing healing to occur for students, tribal members, and educators.

Student objectives (outcomes):

Students will be able to: Make a similar map to Feathers’, based on length of time, populations, names and landforms, and any rivers within a 10-mile area of their home.

Essential Question(s):

How well did the Native people of the west understand their homelands?

How does our knowledge of our area compare to Feathers’?

ASSESSMENT EVIDENCE

Suggested Formative Assessment of Learning Outcomes:

Students form groups of four and examine and discuss the three maps provided. Students record answers to the questions: How are all three maps the same, how are they different? How does the oral tradition of map making differ from written culture of Europe? How much of our landscape do we carry in our mind’s eye?

Culminating Performance Assessment of Learning Outcomes:

Students will create their own maps of the 10-mile radius of their home and include the information about their neighbors, the neighboring houses, including their colors, trees, fences, cars, pets, patios, or any other distinct details.

LEARNING MAP

Background: Reading material is included in this lesson. The students will review the maps and read the stories that explain where the maps came from and how they were used over time.

Entry Question(s): Where did Lewis and Clark’s original map come from? How was it created and what makes it unique? Can each of us make a map like Feathers’, and how large of a territory can it be?

Materials: Written passages describing the three maps being utilized. Three maps for review. Paper and pencil/colored pencils to create their individual maps of their community/neighborhood/region.

Learning Modalities:

- Auditory: Students can read aloud the story of Feathers and Peter Fidler.

- Visual: Students observe the maps and examine and analyze their similarities and differences.

- Kinesthetic: Students can go outside to review the local landmarks and get a sense of space and distances.

- Tactile: Students create their own maps utilizing Feathers’ system of “centering”, starting to create the map from the “center,” or wherever you are; identify the four directions, time to get to areas, the names of the people and/or groups who are located in spaces on the map.

Situated Practice: Students will receive the materials and be given 10 minutes to review and familiarize themselves with the information in the story and on the maps.

Overt Instruction: After students have a chance to read and examine the maps being used, the teacher will set up the lesson procedure by posing the essential questions out-loud to students. After taking a few comments and answers, the students will form groups of four. The groups of four will be divided into partnerships and each duo will create one map. Students will be instructed to start where they are and create a map that basically covers at least a 10-mile radius, but it could be much larger if they choose. After students complete their maps, they complete the assignment by selecting a friend who has supported them and helped them gain knowledge in their lives, and honoring that person with a gift to show their appreciation.

Critical Framing: The oral tradition of the Northern Plains tribes is a sophisticated and comprehensive system of knowledge and values that includes spoken language, sign language, geographic and social knowledge, and community cohesion/reciprocity.

Transformed Practice: Understanding the rich depth of the oral tradition and its broad application to knowledge and culture is an important concept for learners because it contrasts with the notion that tribal communities in the Northern Plains were colloquial and had little knowledge outside of their tribe and their immediate area. In fact, the oral tradition was remarkably extensive, inclusive, and multi-cultural/tribal in its nature. The trade culture of the region supported and maintained that remarkable oral tradition.

Differentiated instruction for advanced and struggling learners: Struggling learners can work with an aide or other students who are advanced readers to assist them in familiarizing themselves with the reading portion of this lesson. Advanced students can create their maps utilizing computers and read further about the importance of multi-culturalism in both the ancient and modern world.

Bibliography and Additional Resources:

Warhus, Mark. Another America: Native American Maps and the History of Our Land (St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998). ISBN 0312150547 (ISBN13: 9780312150549).

Willner, Dana. “They Talked with Their Hands” Graduate Student Essay, Montana State University, n.d., n.p.

Using Primary Sources: Original maps that came from the late 18th and early 19th century that were used by Peter Fidler and Lewis and Clark.

Background:

Tribal Oral Tradition in the Expansive and Cosmopolitan Northern Plains

For many thousands of years, the Native peoples of the Northern Plains traveled in a circular pattern throughout the year, exploring the landscape on foot and later by horse, and learning with remarkable detail every river, mountain, tree, and neighbor for thousands of square miles. The oral traditions that empowered this type of encyclopedic knowledge of the earth included songs, ceremonies, histories, stories and recollections, constant interaction with the other groups who shared the land with them, and finally the ground itself. The unique landscape of the Northern Plains, which is predominantly grasslands with scattered island mountain ranges, makes the memorization of the terrain much more viable than any area dominated by forest or woods. This lack of trees to block the line of vision make it a place where great distances can be observed from nearly any geographic point; huge swaths of land and every star in the night sky are in plain view. The following maps represent the incomparable knowledge of the earth that Northern Plains people possessed, and the generous way that they lived and shared their knowledge.

Situated Practice:

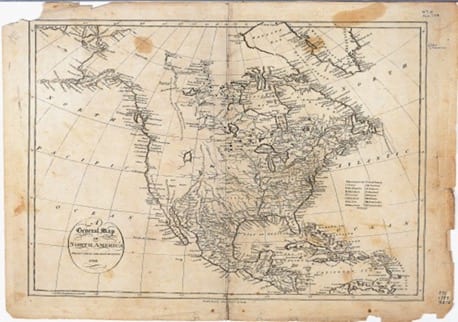

The map of America below was created in 1795 by John Reid of New York. It was the most complete map of north and central America at the time it was published and was accurate for the areas east of the Mississippi River and south of the South Platte River, including all of Mexico. However, the northwestern portion, where the upper Missouri River is located, and the Rocky Mountains dominate and create the Continental Divide, is almost completely blank. The marks that are drawn in the northwestern area of the map are inaccurate, indicating how little the Europeans understood or knew about this region. As the map indicates, this area of the continent was the last to be fully explored and remained a mystery until late in the 19th century. Even the famous Yellowstone Park wasn’t officially surveyed until 1872 when the Washburn Expedition brought scientists, map-makers, and photographers into that now world-famous mountain plateau, America’s first National Park.

Overt Instruction:

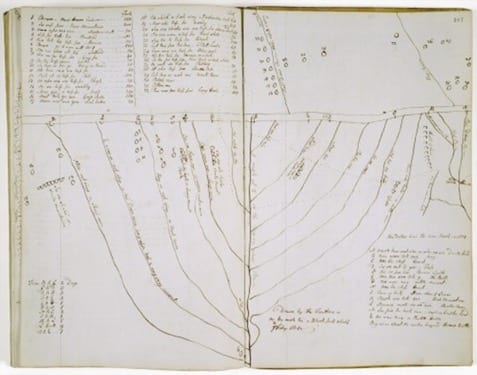

The map below comes from a Hudson’s Bay Fur Company surveyor named Peter Fidler, who drew it based on the explanation provided to him by a Blackfoot elder named Feathers. Feathers provided this information for the Hudson’s Bay Company so that the representatives of the fur company could travel throughout the region to contact tribal communities and start fur trade relationships with them. It includes the mountains, rivers, tribes, distances, and numbers of people living there. This map described an area that was previously completely unknown to the Europeans. Read the story below to learn more about it and what it signifies. The map is courtesy of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, T11048, in the Archives of Manitoba, and published online by the Newberry Library. See also this interactive version, hosted by Learner.org.

When Thomas Jefferson and the early U.S. government made the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon, only Native Americans of the region understood the geography of the region. All of the official maps made by Europeans and Euro-Americans were inaccurate and void of information beyond the upper Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains. The first European to acquire a comprehensive description of the Northern Plains was Peter Fidler, who was a surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Fur Company. Mr. Fidler had come to the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains in September of 1800. With his team, he established the “Chesterfield House” trading post at the junction of the Red Deer and South Saskatchewan rivers, east of what is now Alberta, Canada. Wanting to understand more about the geography of the region, he requested that the local tribes inform him about their homelands. Responding to his request, a Blackfoot elder named Ac ko Mok ki, or “Feathers,” came to Fidler in February of 1801 to provide him with a comprehensive map of the region.

Ac ko Mok ki shared his mental map of the area based on the ancient tribal oral tradition of the Great Plains. As with sign language or other Plains Indian ceremonial traditions, Feathers began his description of the region from the exact place where he and Peter Fidler stood. To transfer his mental map into a form that the surveyor could understand, Feathers asked Mr. Fidler to go outside so he could draw out his map on the ground, which Fidler then copied into his journal. Starting with the Red Deer and Saskatchewan rivers flowing eastward, he then made two long parallel lines to symbolize the Rocky Mountains, which he indicated were the source of the waters. His map of the Rocky Mountains included the most prominent features of the ranges and how many days’ travel it would be between them. From the east, he drew in all the major rivers that fed into Missouri, starting in the north with Milk River in Alberta and going over 500 miles south to the Bighorn River in Central Wyoming. On the west side of his depiction of the Rocky Mountains, he drew in the Columbia and Snake Rivers, and the west coast of the Pacific Ocean. His images indicated that there was no river that crossed between the Rocky Mountain Range, only rivers on either side. He went further to describe the entire landscape, including where there were forests and grasslands. Then he went about filling in the map with information about the people who lived in the area, providing Mr. Fidler with the locations of 32 different tribal groups, including the names of the tribes and the head men, the total community populations, and days’ travel between the groups. All told, Ac ko Mok ki’s map included over 200,000 square miles of North America, an astonishingly voluminous amount of information that stands out as the largest geographic description ever provided by Native peoples of the west and recorded by non-Indian cartographers like Fidler.

Peter Fidler sent his transcribed version of Feathers’ map back to the Hudson’s Bay headquarters in London with a note, stating that the map described areas previously unknown to many Europeans. The map was copied and then used by European map-makers of the day to help them create new and more accurate maps of the west. The new maps were copied and distributed in the summer of 1801, and three years later the Lewis and Clark Expedition followed the path that Feathers had shown Fidler.

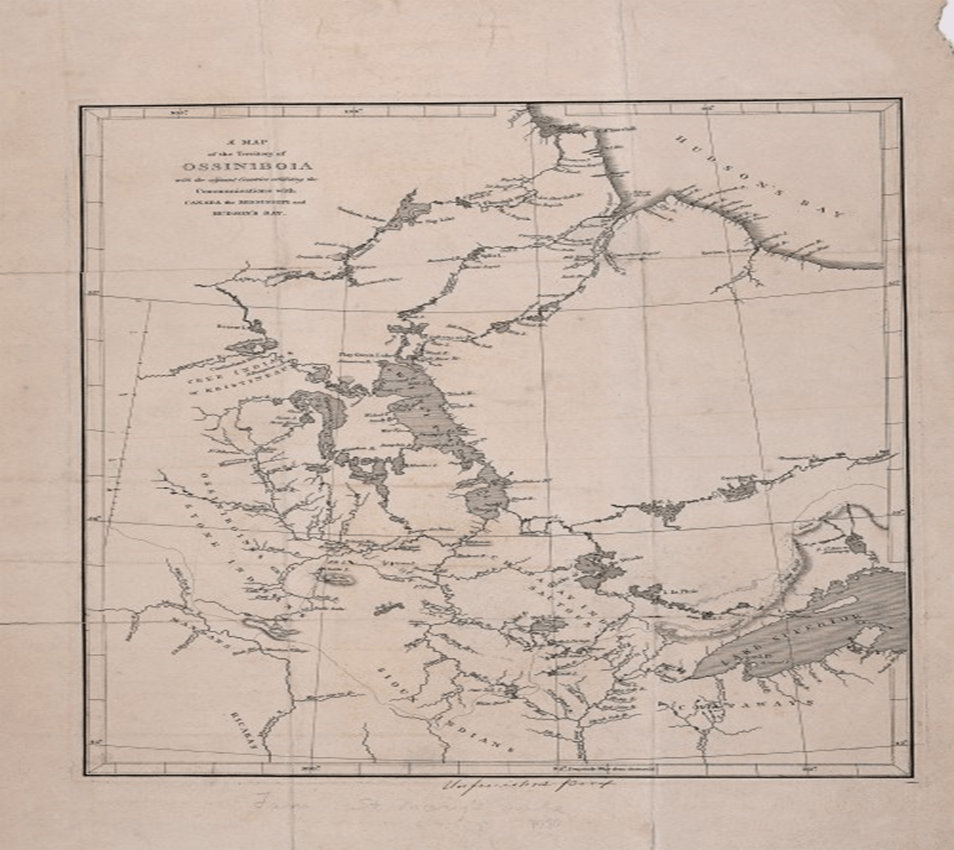

The map below, which includes some of the information that was passed along to Peter Fidler by Ac ko Mok ki, was made in 1801 by cartographers who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company. This was the first official map that identified tribal territories. The map was entitled “A Map of the Territory of Ossiniboia,” which was taken from the Nakota Sioux tribal name “Assiniboine.” This is one of the maps first used by Lewis and Clark when they left St. Louis for the Pacific Ocean in 1804.

If you examine maps of this similar area today, you will notice that they are covered with the names of explorers and other men who are figures of non-Native American history. These places had names before they were mapped and renamed by non-Natives, as the map made by Ac ko Mok ki very well shows. Why did non-Native names take precedence on the maps carried forward into our history by non-Native explorers?

Critical Framing:

Knowing and understanding the geography of where we live has always been an important part of being a successful person, because traveling is an essential part of our lives. How can we learn more about our region and the people who live there? Consider at least three different ways to learn about the areas where we live, go to school, work, play, shop, and engage with our friends. How does our knowledge compare to the knowledge of Ac ko Mok ki?

Transformed Practice:

As we reflect on who our knowledge-holders were in the past, it’s important to consider their influence on our present. It is also important to consider who our knowledge-holders are today. In Plains Indian cultures, the giveaway is a common way to acknowledge the fact that when an individual makes progress in life, it is always through the contributions of others. Native people who achieve special accomplishments in life are recognized at giveaways when they honor those who contributed to their lives by giving them gifts. A fundamental belief of this ceremony is that honoring others brings honor to a person’s life. If you had to host a giveaway today, what would yours look like? What accomplishments have you made in life that you feel are significant? Who helped you achieve these and how can you honor them for what they have given you? Your assignment is to give credit where credit is due by acknowledging publicly that you didn’t get to where you are in life without the contributions of others. Choose two people you wish to honor. Explain how they have contributed to your life and devise a way to show them that you recognize what they have given. (If you choose, your class may hold a day of honor and invite those the students chose to attend an event. Students can present their honoring projects to their honorees during the event.)

Differentiated instruction for advanced and struggling learners:

Everyone needs to say thank you. This assignment gives all students a way to express gratitude from their hearts and their projects, though hopefully very diverse, should reflect this.

Using Primary Sources:

The maps used in this lesson are the original maps used during the early 1800s.