(This is Lesson Plan 4 for Crystal Boulton-Scott and Joseph Scott’s curriculum, “Tribal First Foods: American Indian first foods, legends, and traditional ecological knowledge along the route of the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery.”)

Essential Questions

How do important First Foods shape the lifeways of traditional Kalapuya bands, and what role does valley camas play in the Seasonal Round recognized by Kalapuya bands since the beginning of time?

How can this recognition of the importance of Seasonal Rounds be conveyed through symmetry found in the camas itself?

How is the time-immemorial recognition among Kalapuya peoples of the need to tend the landscape using agricultural techniques such as seeding, thinning, and burning borne out by the scientific observations of colonizers?

First Foods Education Concepts Review

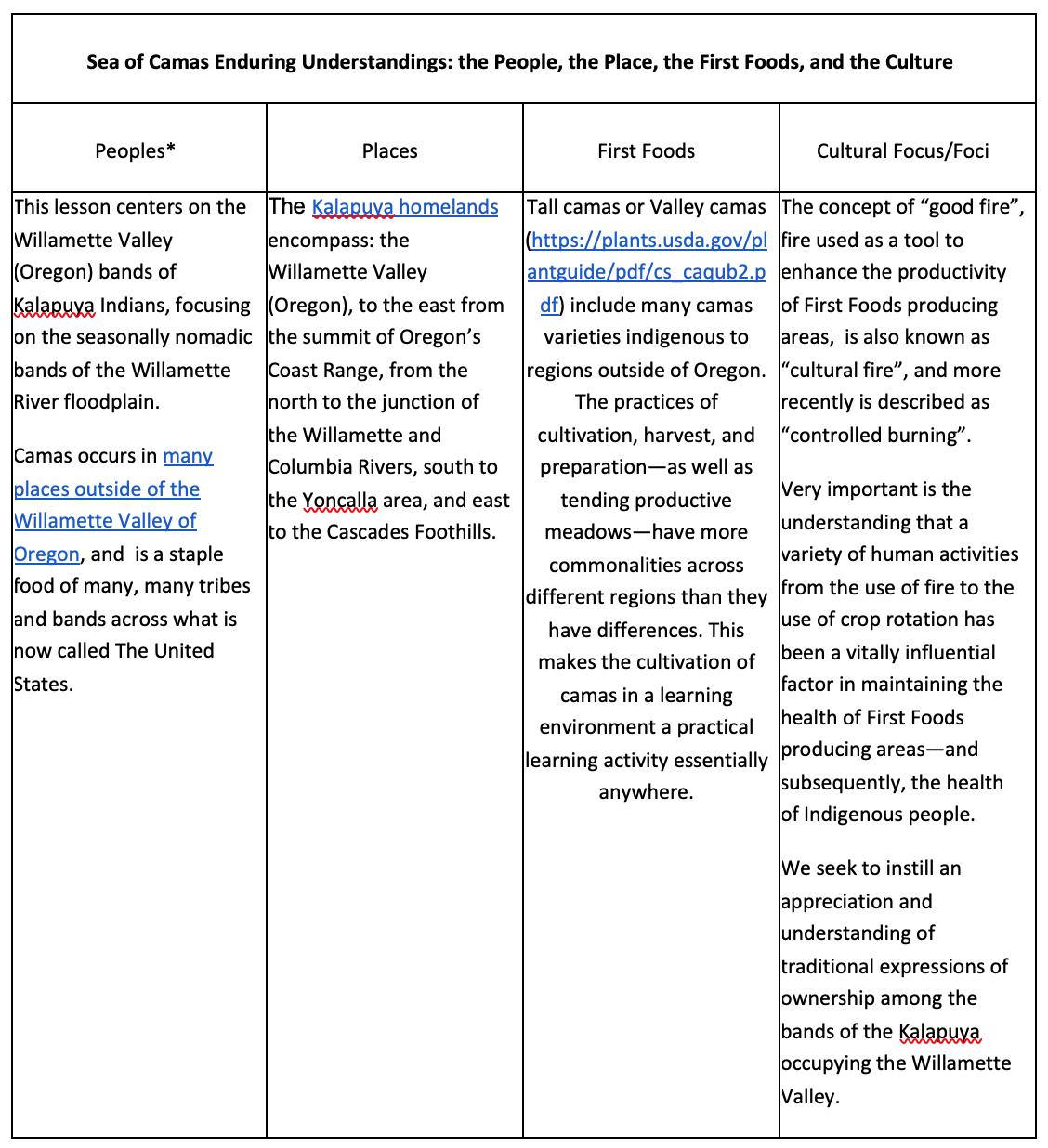

The exploration of first foods goes far beyond the study of plants and animals crucial to the dietary needs of tribes encountered by the Corps of Discovery and the Euro-American settler-colonists who came in their wake. First foods embody a deep and sacred understanding of self and place. These understandings shape tribal societies and guide the Seasonal Rounds that tribal people have made since the beginning of time as they pursue physical, cultural, and spiritual prosperity. Carried within these rounds are the laws of Creator, the values of the people, and an understanding that tribal people are not simply from a place. Tribal people ARE that place as much as any other part of the landscape. The knowledge of traditional foods is often where Western science and traditional ecology meet. In good times, first foods are plentiful, lush, and full of the nutrition that sustains old and new generations. This is a time for celebration. In hard times, the Human Beings know in their hearts that the Creator has purpose and justification for sending a challenge. Tribal ways of knowing offer non-Natives a science for the academic understanding of traditional knowledge.

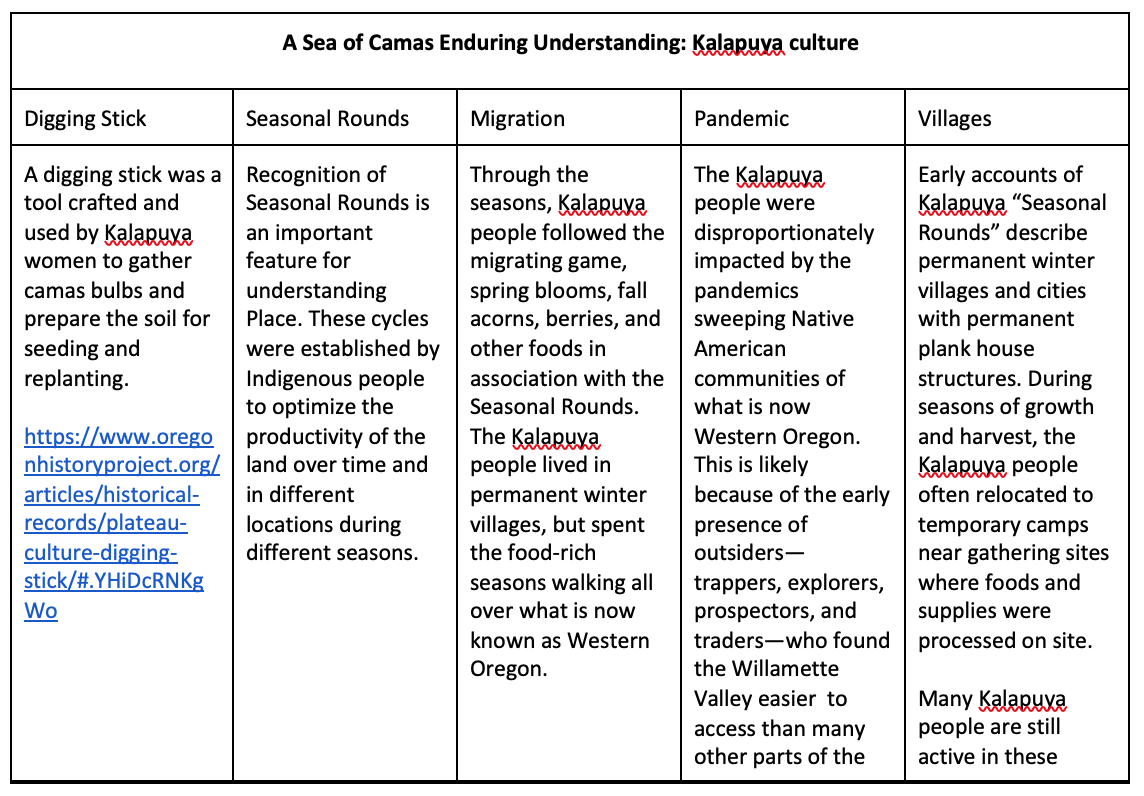

It can be a surprise to educators and students to learn that private property among the indigenous people of what is now the Pacific Northwest was (and is) a prominent feature of tribal cultures. This includes geographic claims. For example, among coastal peoples, a particularly productive spot for the gathering of bird eggs could be owned and controlled by an individual, family, or village. Tribal bands often required permission from travelers in order to provide for safe passage across territories. Hunting, gathering, and prayer spots, and other significant locations were often claimed for exclusive use, and the consequences of trespass might be dire. Depending on the violation, indiscretion might cost a bad actor their freedom.

The fields of camas that bloomed like blue seas in the spring, and that ultimately sustained the people throughout the year were (and again, still are) often identified as the exclusive territory of families, villages, and bands. Outsiders were required to obtain permission before harvesting the camas, yampa, tarweed, and other foods found in a productive area, and the people in charge often upheld and enforced their own techniques and protocols. As with all tribal communities, cultural norms—including those guiding the gathering of First Foods—are highly variable from group to group.

At the same time, some areas are regarded as common property. This would include hunting grounds in the mountains, berry patches, rich root digging spots, and estuaries full of clams and game.

Some of the very first conflicts that arose between tribes and outsiders came from a disregard for these basic protocols. At first contact, many trappers, explorers, and others passing through tribal territories sought permission. As more and more outsiders cast their eyes toward the rich landscape and resources of what is now Western Oregon, the more common it became for these outsiders to take without asking—in clear violation of community norms.

(An interesting exercise in affective thinking among young learners might be to discuss what it feels like to share something with fellow learners who ask nicely, and move toward feelings potentially evoked in situations where fellow learners take without asking. This becomes a “real world” lesson when educators and learners revisit some of the mutually agreed-upon norms of the learning environment—particularly “Respect”.)

The importance of fire in the maintenance of food gathering and hunting areas cannot be overstated. Many tribes and bands of this place will identify themselves as “Fire People” as commonly as any other identity; Salmon People, Ocean People, Upriver People, and the many other Peoples in what is now called the Americas. It is very important to recognize fire as a fundamental element, no better or worse than any of the other basic elements (water, earth, and air). Colonization, and the imposition of colonizing concepts have often contributed to an understanding of fire as an enemy of the “natural world”. This is far from accurate. Fire is natural, and the production of traditional First Foods exists on equal footing with rich soil, fresh air, and clean water. The traditional use of fire in modifying and enhancing a camas habitat serves a variety of purposes, including everything from breaking the thatch layer to eliminating uninvited plants and animals. Educators might encounter “pushback” when helping learners to understand the importance of “good fire”.

In the approximately two hundred years that have passed since the first contact, outsiders have suppressed good cultural fire; they have used copious amounts of pesticides; they have brought unfamiliar domesticated animals that trample productive grasslands, destroy riparian zones, muddy salmon spawning beds, and displace native game animals. Unwanted and counterproductive species of plants and animals have been introduced, and more recently, the genetic modification of plants and animals and other questionable scientific practices have created a “perfect storm”, robbing indigenous people of their sovereign right to gather healthy foods from their usual and accustomed places. Traditional diets have been replaced by historically unfamiliar diets that are high in saturated fats, salt, sugar, preservatives, and artificial ingredients. Access to medicines, and the knowledge of this combination of First Foods, medicines, place, spirit, and self, remains under constant assault. Another excellent learning opportunity for both educators and young learners is to study the elements of a healthy diet and the impact of less healthy foods on the learners’ culture.

Use “Assessment 1: First Foods Enduring Understandings” Rubric to evaluate the understanding of the following:

*Many varieties of camas exist across the United States, and many of the tribes and bands encountered by the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery ate and traded camas-based preserved foods. The numerous bands of Kalapuya people traditionally lived and thrived in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, and, upon being forced from their homelands, have continued to do so as members of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz and Grand Ronde.

|

A Sea of Camas Enduring Understanding First Foods: the camas plant |

|||

| Bulbs | Leaves | Flower Stalk | Flower (details, including flower parts and symmetry) |

| The plant and its individual parts, as well as resources for exploring concepts of symmetry, are illustrated and included in the Lesson 4 Support Materials folder. | |||

|

A Sea of Camas Enduring Understandings: Encounters with the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery |

| Camas can make people sick, particularly when undercooked. In addition, consuming too much can cause gastric distress. The Corps of Discovery had a rather unfortunate introduction to the camas plant as a food staple. See:

The Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery was tasked with, among many other things, the use of journals in the illustration, documentation, and description of flora and fauna on their trip. The use of these elaborate descriptions and samples often reflects a focus shared by many newcomers to the western homelands of tribal people on identifying life and landscapes ripe for commercial exploitation. They also gathered and preserved samples of some plants; this activity is replicated as “flower pressing”, following the included instructions. It has been alleged that no members of the Corps of Discovery had direct contact with the Kalapuya people, and in fact missed the Willamette River entirely. This allegation is subject to some controversy. |

*The following website has a tremendous amount of information on camas – digging, preparing, cooking, and eating: http://www.orww.org/Bald_Hill_2004/Native_Plants_Tour/Ashland_Camas_Bake/index.html

|

Cultural Universals focus of lesson 4: A Sea of Camas |

|||

| Food | Transportation | Entertainment | Government |

| Clothing | Science | Communication | Tools/Technology |

| Shelter | Medicine | Medium of Exchange | Family/Kin |

| World View | Arts | ||

First Foods environmental teaching and learning

The exploration of first foods goes far beyond the study of plants and animals crucial to the dietary needs of tribes encountered by the Corps of Discovery. First foods embody a deep and sacred understanding of self and place. These understandings shape tribal societies and guide the rounds that tribal people have made since the beginning of time as they pursue physical, cultural, and spiritual prosperity. Carried within these rounds are the laws of Creator, the values of the people, and an understanding that tribal people are not simply from a place. Tribal people ARE that place as much as any other part of the landscape. The knowledge of traditional foods is often where western science and traditional ecology meet. In good times, first foods are plentiful, lush, and full of the nutrition that sustains old and new generations. This is a time for celebration. In hard times, the Human Beings know in their hearts that the Creator has purpose and justification for sending a challenge. Tribal ways of knowing offer non-natives a science for the academic understanding of traditional knowledge.

When and where will this lesson take place?

Historically, the most intensive cultivation practices of harvest, replanting, seeding, preparing, storing, and burning (pyroculture) occur during spring and fall. For teaching and learning purposes, these seasons and basic interpretations of their associated cultural cultivation practices can be used. It would be very challenging and a culturally dubious endeavor to attempt the cultivation of camas anywhere but outdoors. Flower pressing, performances, and other summative expressions can be conducted indoors and independent of season, although flower-pressing will require access to fresh flowers.

Tending camas is a year-round endeavor. Spring tending involves the identification and removal of “death camas” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxicoscordion_venenosum) and other disruptive plants.

As the camas flowers fade in late spring and early summer, nutrients are drawn back down into the bulbs. In some places, bulbs are harvested and prepared for storage, trade, and consumption. Traditionally, women tend patches using a special digging stick, tilling the soil, harvesting some bulbs, and distributing smaller bulbs to mature for future harvests. Later in summer, the soil dries and hardens, making harvest impractical. Seeds are gathered and either saved or used to re-seed areas where camas are sparse. In the fall, before heavy rains, the Kalapuya burned meadows to control grasses and thatch buildup, as well as to prevent trees and shrubs from encroaching on the camas patches. During the winter season, camas patches are generally left untouched, although seeding during wet times and burning during dry times might occur. This cycle continues as springtime starts. Camas leaves are some of the first to emerge from the soil as warmer spring weather takes over. Flower stalks appear practically overnight, and can quickly grow to be four feet tall in places. Once the flower buds mature, they open from the bottom of the stalk, and bloom upward and begin to fade as spring turns to summer again. Thus, the cycle continues.

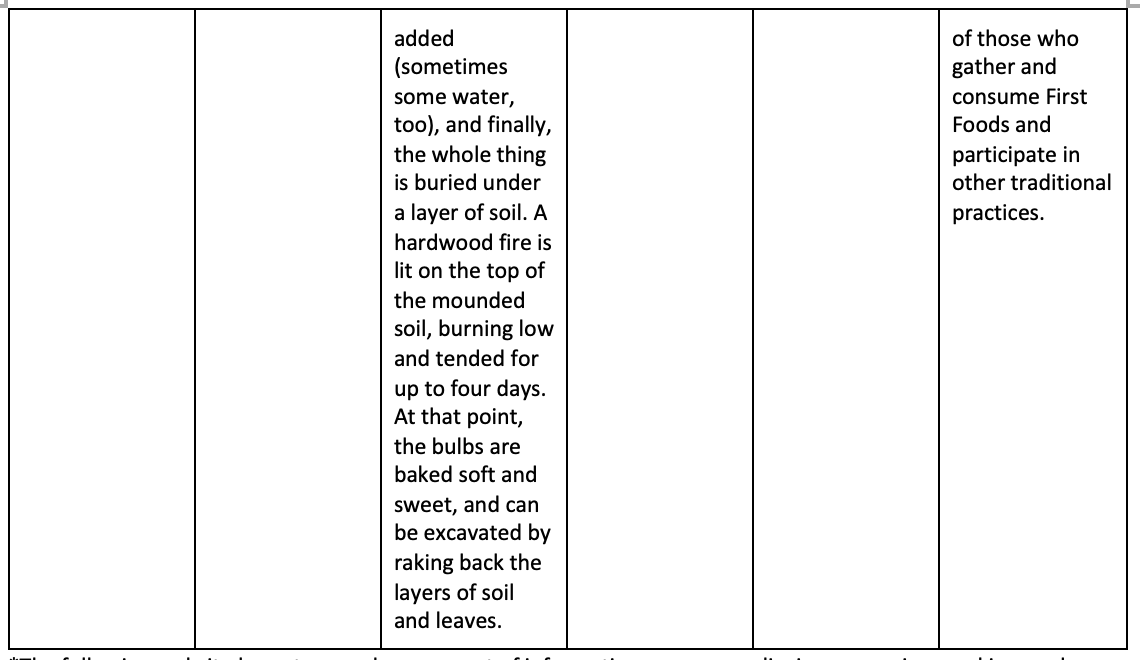

The ideal time for harvest varies by location, cultural norms, and the needs of the community. After the rains begin in fall, the soil becomes soft enough for digging, and the bulbs seem sweetest at this time. This is also a good time to use a pit oven for baking.

With whom will you collaborate to make this project successful?

Local tribes often fund and maintain tribal seed banks, gardens, and programs to support a return to healthier indigenous diets, and to help tribal people assert their sovereign rights to produce and consume the First Foods of their ancestors. Nurseries operated by non-tribal people can provide camas seeds and plants; tribal sources would be preferred for a variety of reasons, including attention to regional genetic stock, traditional cultivation, and supporting tribal businesses.

Camas is essentially grown in a garden setting, although it often takes the appearance of a meadow. A local property owner with fallow land would be an ideal partner, particularly if that property is under the watch of a local tribe. When cultivating camas in pots, consider culturally appropriate options: biodegradable pots, compost, and smaller-scale culturally accurate tending as described in the lesson.

Entry Question(s)

After completing lessons and activities, learners and educators will be able to answer the following:

- Identify tall/valley camas.

- Describe camas harvest methods.

- Understand the construction and use of a camas digging stick.

- Cultivate, harvest, cook, and taste camas bulbs. (This activity will be somewhat dependent on the varieties of camas indigenous to the geographic area.)

- Experiment with the four basic elements in relation to their contribution to plant growth and health.

- Explore camas in the context of element and season, explored in Lesson 1: Healthy Learning

- Describe the role of camas in keeping a healthy traditional lifestyle. Including physical well-being.

- Describe the negative impacts of grazing, pesticides, and invasive forms of agriculture (among other influences) on healthy camas.

- Identify camas as a trade item, and explain the function of “ownership” in the context of Kalapuya First Foods.

- Place major cultivation, harvest, preparation, feasting, and storage events conducted among the Kalapuya in a circle, emphasizing the seasonal/cyclical nature of these activities.

- Recognize that the neglect suffered by camas patches and other productive landscapes throughout the Willamette Valley is the result of a devastating exposure to European invaders

- Share some understanding of the fact that the cultural practices and techniques necessary for maintaining what is now known as the Willamette Valley as a nourishing place for the Kalapuya include controlled fire, careful tending through indigenous methods of cultivation, and a physical and spiritual tie to the land itself.

- Distinguish between “good” fire and destructive fire.

- Identify basic flower parts, as well as types of flowers.

- Identify the symmetrical features of different flowers and flower parts.

- Understand the mathematical connections between angles, symmetry, fractions, and natural phenomena.

- “Press” flowers. (See the instructions included in Lesson 4 Resources folder)

- Perform a skit about the seasonal nature of the growth and regeneration of First Foods plants. (See the script, props, and other materials in the Lesson 4 Resources folder)

Extension Activities:

- Gather materials and construct a camas digging stick, either miniature or of a usable size. If it can be used, demonstrate how to dig with it. (Not necessarily camas.)

- Investigate the work of botanists such as David Douglas, as well as the information-gathering aspects of the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery to see what illustrated and preserved plants look like.

- Explore how cooked camas can be preserved and used as a trade item.

- Create a traditional pit oven and use it to cook root vegetables or tubers.

Lesson Procedures:

- Learners locate Kalapuya homelands on a map of Oregon, and recognize that there are a number of different bands in this area. (Learners and educators should understand that they have similar cultural practices.

- Describe Kalapuya “Seasonal Round”, recognizing students’ preferred form of expression—short story, poem, illustration, etc..

- Learners develop a project designed to describe a specific feature of Kalapuya culture; learners may wish to work in groups to create something more comprehensive. (It is crucial for learners to understand that many Kalapuya descendants live throughout Oregon and elsewhere in the world, and are associated with the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians and the Grand Ronde Community. Cultural practices, including those associated with camas, are still regularly practiced). This activity should, at the very least, include details about camas as a food and trade item (cultivation, gathering, and eating), details about Kalapuya seasonal rounds, cultural fire, and the concept of family/village property. (Use First Foods Cultural Activities Rubric to guide the development and assessment of these projects.)

- Learners use the included photographs and illustrations in learning to identify camas, specifically tall (valley) camas.

- Learners use these same resources to learn the various parts of a mature camas plant. (This is an opportunity to learn that there are some plants that share camas characteristics, while there are others that do not, and to do a “compare and contrast” among various indigenous food plants. Consider including a revisit of Three Sacred Sisters.)

- Learners grow camas, starting with seeds, bulbs, or both.

- Educators and learners study traditional camas harvest methods

- Learners color and otherwise illustrate flower types, flower parts, and symmetry concepts.

- Learners color, study, dissect flowers.

- Learners demonstrate/illustrate harvest.

- Learners relate symmetry to the cycle and create a cycle illustration of their choosing. This could be a cycle studied earlier in the unit, cycle students are already familiar with (the water cycle, for instance

- Learners use pesticides.

- Learners perform “I am a Flower”, a skit that revisits the concept of cycles and illustrates the major stages of plant growth. The script and prop materials are found in the First Foods Lesson 4 Support Materials folder. (Use Assessment 3: Story Response Rubric to guide and assess learner effect on this activity.)

Materials and supplies:

For sprouting camas plants:

A windowsill, greenhouse, and/or outside space.

Egg cartons or some variation of a biodegradable pot.

Soil(s), seeds, bulbs.

For demonstrating traditional harvest methods:

There is a picture of a traditional digging stick included in the First Foods Lesson 4 Supplemental Materials folder; however, crafting one is no easy task. It is a lesson in and of itself and is an excellent example of the ecological and technical wisdom of Kalapuya people. With that in mind, an educator can use alternatives, such as a metal rod or a shovel handle.

Materials and supplies for studying flowers (in general):

A flower press—these can be purchased pre-built, and/or there is a technique described and illustrated in the First Foods Lesson 4 Supplemental Materials folder.

Flowers—fresh blooms, ideally from camas plants, but any flower big enough to enjoy, and small enough to fit in the press will work.

Illustrations found in Lesson 4 Supplemental Materials, and/or arts and crafts supplies. The printouts are a very simple way of making both examples of blossoms used in this lessons’ symmetry component, and to

*While access to many resources is available by way of the Internet, one cannot assume that reliable and consistent access to electronic media is a given. All of the tribes and bands addressed by these lessons offer resources beyond those found electronically. Printed and recorded language teaching and learning materials are available directly from tribes, as are similar tools related to culture and history. Most tribes have in their possession —or have access to—primary documents describing their encounters (and/or the effects of these encounters) with the Lewis and Clark expedition.

For the camas experimentation and dissection activities, you will need:

- Small pots or egg cartons

- Some variety of growth medium.

- Camas sprouts or immature bulbs (Other bulbs will work, preferably something small, like crocus. Avoid “layered” bulbs, like onions or shallots.

- Coloring page illustrations of flower types, flower symmetry, and camas flower parts, found in the First Foods Lesson 4 Support Materials folder.

*For crafting a traditional camas digging stick, you will need:

- A three- or four-foot long length of “green” wood. Ideally, this would be a freshly harvested branch from maple or other hardwood trees. Once it’s shaped according to the included image with a curved tip, it should be “fire-hardened”—exposed to enough heat to dry it into the curved shape, but not enough heat to cause flames.

- A handle. Traditionally, this would be a carved elk antler or another piece of wood. Look closely at the included image, and you will find that the handle has a square hole fitted over a square peg at the top of the stick. Using a screw to attach the handle works as well, as long as it stands up to the twisting action required to excavate bulbs.

- The illustration of a Kalapuya/Columbia digging stick, found in the First Foods Lesson 4 Support Materials folder.

*This task is challenging. The digging of camas bulbs is just as effectively accomplished using a shovel, crowbar, or tool handle. I do not recommend this as a classroom activity, but it makes a great demonstration. The cultural practice of digging roots, tubers, and bulbs extends the length of the Lewis and Clark Trail and, in fact, throughout what is now called the Americas.

Consider inviting a tribal elder or other First Foods expert with appropriate knowledge to visit and offer a demonstration. Another option is to create miniature digging sticks using – much smaller sticks.

For the craft and performance activities, you will need:

- The flower press guide found in the Lesson 4 supplemental materials guide. Ideally, the flowers to be pressed will include camas blossoms. Other types of blossoms may be more accessible, and therefore more appropriate.

- The “I Am A Flower” script and props, found in the First Foods Lesson 4 Support Materials folder.