PRIMARY SOURCE

The Alcatraz Proclamation, 1969

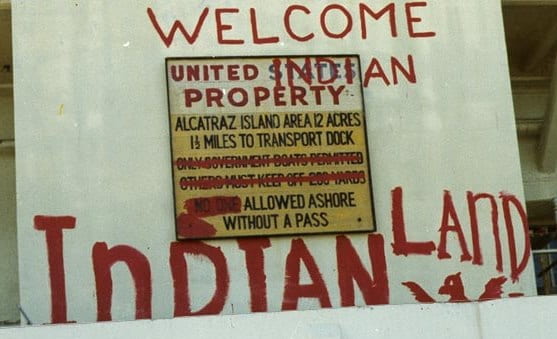

Sign on Alcatraz Island, 1969.

(photocredit: Wikipedia, Noncommercial Reuse)

INTRODUCTION

by Stephanie Wood, University of Oregon, Honoring Tribal Legacies

In 1962, three inmates made a dramatic escape from the prison on Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay. My family was in a fishing boat very near the island that day, and we shivered when we got home that evening and saw on the TV news that there had been an escape, with the men believed to have tried to reach their freedom by using an improvised raft. We felt lucky that they had not approached our boat, asking to come aboard. Their fate is still a matter of debate today. But such moments of attention drawn to Alcatraz in that period were rare. The penitentiary was closed in 1963, and the U.S. government declared the island “surplus federal property.”

The next year, in 1964, a few Sioux men, led by Richard “Dick” McKenzie (from Rosebud, South Dakota) decided to try to occupy the island. But they only held it for four hours. More lasting efforts came about in late 1969, not coincidentally as Thanksgiving, a long contested holiday, approached. Five men, including Richard Oakes (Mohawk, a student from San Francisco State), Jim Vaughn (Cherokee), Joe Bill (“Eskimo”), and Ross Harden (Ho-Chunk) jumped off a boat and swam to the island on November 9th. In an ironic move, they claimed Alcatraz by “right of discovery.” The U.S. Coast Guard intervened to remove them, but fourteen more American Indians arrived again that day and spent the night there, before departing. The Proclamation was already in hand on the 9th.

On November 20th, and despite a blockade by the Coast Guard, 80 American Indians got support from “free-spirited boat owners of the No Name Bar” in Sausalito (according to the video, We Hold the Rock) and moved onto the island under the cover of darkness. This was an unarmed, peaceful occupation that would stretch over a period of about a year and a half. Women, such as the student leaders LaNada Boyer (now Dr. LaNada War Jack, Shoshone/Bannock) and Shirley Guevara, plus children and some non-Native sympathizers, such as college students from around the Bay Area and from UCLA, were a part of the occupation. The New York Times reported on December 12, 1969, that possibly “a thousand Indians” were on the island. One of the participants estimated that some 15,000 people, many of them Native, came to visit the occupiers in the early months. Lots of them identified with the “Red Power Movement,” but the occupiers referred to their group on the island as “Indians of All Tribes” (IAT).

Identification cards given to occupiers, such as Edward Willie (Paiute/Pomo), born in 1953, referred to “Indians of All Tribes, Inc.” It was the IAT that issued the Alcatraz Proclamation to explain their position to the world. Proclamations hold a special place in history. They have been a means for individuals and groups to put forth their political positions, to declare their stance on an issue. They can also come from the government, directed to “the people.” In the case of the Alcatraz Proclamation, the IAT sought to educate the descendants of colonists about injustices in American Indian history, such as land-grabbing, the U.S. government’s “termination” policy (an effort to take away tribes’ special status and assimilate them into the larger population), and broken treaties.

In a follow-up letter to the Proclamation, written on December 16, 1969, the IAT would also speak of the desire to have a Cultural Center and a college on the island, with more positive attention to religion and spirituality, ecology, a training school, and their own museum, and these things are spelled out in some detail in the addenda on the Proclamation itself. The group wished to prompt the emergence of a new relationship with the U.S. government characterized by peace and justice.

Dreams for the utopian future of Alcatraz were never fully realized. Very early into the occupation, the stepdaughter of one of the leaders, Richard Oakes (Mohawk), experienced a terrible fall and died from head injuries. He would soon leave the island, and by 1972 he had been shot dead at the age of 30 by a white supremacist in Sonoma, California. More and more non-Native people were coming onto the island in 1970–71; some were bringing the drug culture with them. Buildings lacked water, so there were no flushable toilets. Wood was being pulled from buildings to burn for fuel to heat the buildings in the cold winter nights, and copper wiring and tubing was being removed from the buildings to sell and raise cash.

The U.S. government, instead of attacking the occupation outright, had opted to try to find other means to get the people to leave, shutting off power (which reduced media publicity coming out of the island) and removing the supply of freshwater that came from a barge. At least five buildings were burnt down, somewhat mysteriously, after the fresh water source was removed. But finally, federal marshals invaded the island on June 11, 1971, and took away six men, five women, and four children; ironically and perhaps intentionally, this was nine years to the day from the dramatic prisoner escape. The island, once offered for sale for $2 million and planned to host a casino and elite residences, would instead be named a National Park and become a destination for tourists heading over on ferries from San Francisco.

Not all the demands of the occupiers were in vain. While they never got full title to Alcatraz Island, Nixon did return 48,000 acres of land to the Taos people, along with Blue Lake. A Native American university was established near UC Davis, California. And, the Bureau of Indian Affairs began hiring Native Americans. On July 8, 1970, Nixon had formally repudiated the termination policy and, in the wake of the occupation of Alcatraz, he launched a series of reforms aimed at improving the lives of Native peoples, transferring “millions of acres of ancestral lands back to Native people and passed more than 50 legislative proposals supporting tribal sovereignty,” according to LaNada War Jack (in the film, The Occupation of Alcatraz that Sparked an American Revolution), even if some of this legislation would be ignored.

The Proclamation helped put into words the common dissatisfaction with discriminatory and damaging government policies that many Native peoples experienced, along with concrete suggestions for improving the way of life of indigenous communities. LaNada saw the impact of Alcatraz as a “kind of spiritual reawakening of our people” (as she states in the film, We Hold the Rock).

Sample “entry” questions:

Look at the photo of the hide published with the Proclamation, which was the “Declaration of the Return of Indian Land,” also written by the occupiers of Alcatraz. What phrases are written in bold, and what might this tell us about the primary motivations for writing this declaration?

Why would the authors address the Proclamation to “the Great White Father and All His People”? Note the reference to “Caucasian inhabitants of this land.” What is the intended audience?

What was envisioned for the “Center for Native American Studies,” and was this a precursor to a significant development in U.S. colleges? And was the idea for an American Indian Museum a precursor to the way tribes now have their own museums, from their own points of view?

How does this proclamation reveal a vision for a new and healthier life for Native people and, potentially, anyone who might live the way this Proclamation describes?

Consider this a piece of persuasive writing. How do the authors try to persuade their audience to their own way of thinking? How do they construct their arguments? What is the tone? Do you find pride, sarcasm, or humor in it?

Sample “essential” questions:

1) What was taking place in indigenous communities at this time? What was going on in the U.S. that might make allow for or inspire this type of action? Historians urge us to consider context and timing. Think of how the country had seen a growing movement for civil rights, Black Power, Brown Power, and the Women’s Liberation Movement. This was also a time of a burgeoning number of communal communities being established in states such as California. The Native Alcatraz community would make decisions with input and agreement from all, as an example of this utopian ideal.

Further, more immediate precipitating events included the burning of the American Indian Center in San Francisco on October 9, 1969, which meant those who had loved the center were looking to house it somewhere else. Also in October 1969, as a letter from the island written on December 16, 1969 states, V.P. Agnew had visited the convention of the National Congress of American Indians and pronounced in favor of “Indian leadership.” Richard Nixon was president of the U.S. at the time, and he had a lawyer negotiating with the occupiers, rather than move in with blatant military force against the occupiers. His military aggression against Vietnam was a source of great public dissatisfaction with his presidency by this time.

2) Why might the group have taken the name “Indians of All Tribes”? Some have said that this action and the thinking of its leadership contributed to “pan-Indian activism.” The December 16th letter also refers to a new “Confederation of American Indian Nations (CAIN)” and asks “all Indian people to join with us.” How were people from many tribes coming together in this action, and what potential did it hold?

3) This Proclamation, which the IAT also refers to as a “treaty,” proposes to purchase the island of Alcatraz (at a ridiculously low price, much as the land had been purchased from tribes) for the making of an “Indian Reservation.” The group would establish an independent school on Alcatraz and try to “instill the old Indian ways into our young,” as mentioned in their letter of December 16th, because “Indian people have not had enough control of training their young people.” How would this treaty and this reservation differ from historical treaties and reservations across what is now the western states of the U.S.?

Sample “big idea”:

This Proclamation strives to draw attention to land grabbing tactics in the colonization of North America, to the injustice inherent in paying nothing—or practically nothing—and taking huge tracts of land for the occupation of settlers, mostly Caucasians from Europe or their descendants. The late historian/theologian/activist Vine Deloria, Jr (Standing Rock Sioux), looked back on the occupation of Alcatraz as “the most significant Indian action since Little Bighorn.” Ben Winton says “Alcatraz changed everything.” In 1980 the Supreme Court case called “United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians“ decided that the U.S. government’s taking of tribal lands mentioned in the treaty was unlawful, and that the tribe was owed money in compensation. The tribe refuses payment and asks instead for the land to be returned. Thus, a big idea from the Alcatraz occupation is the lasting desire for self-determination and to right the wrongs of colonialism.

Sample “enduring understandings”:

The IAT took a daring action that drew international attention to injustices experienced by American Indians. The action was clever in the way it used models from settler colonialism, turning them on their head, and thereby trying to disarm the opposition they knew they would face and to win ideological support for their action. For example, the first men to occupy the island used the expression “right of discovery” to reclaim it, and this phrase was repeated in the Proclamation. We see from a photo of the water tower that the IAT called Alcatraz the “home of the free.” In a list describing the negative aspects of the island, they highlight the negative aspects of many reservations created by the U.S. government. The occupiers also point to the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), which agreed to return to Native peoples retired, abandoned, and out-of-use federal lands, such as the forts along the Bozeman Trail.

Place-based considerations:

1) Consider why the group chose Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay. The Proclamation states that the island would become symbolic of “the great lands once ruled by free and noble Indians,” to all ships entering the bay from around the world. The irony of having free people living on an island that was once a prison was not lost on the IAT. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei referred to the occupiers as “freedom fighters” and spoke of their human rights, and he made a huge exhibition of multimedia installations and sculptures that were exhibited on the island, 2014–15.

2) This island was largely unoccupied federal land that had fallen out of use, which made it seemingly perfect for a being reclaimed by Native peoples. They wanted a space where they could “hold on to the old ways,” as stated in the December 16th letter. While not so much the first group of occupiers, those arriving to support the movement in early 1970 were city-dwellers. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, some 200 thousand Native people had migrated to U.S cities in the fifteen-year period after 1952, when many of the occupiers were born. Their parents were seeking a better life, and they would have a new vision of that better life, too, one that re-embraced their indigenous roots.

3) Alcatraz Island is not far from the city of San Francisco or from Berkeley, where there was potential for a supply network and people who might like to join the movement. It was not so remote that media coverage would be difficult, so the occupiers’ demands could be broadcast far and wide. Furthermore, it was not far from indigenous communities in Northern California.

4) Note how the Proclamation refers to another island, Manhattan Island, as one of the first places European settlers took from tribes and for a ridiculously low price. Richard Oakes (Mohawk) was from New York, and in 1969 Oakes had met with the Mohawk National Council, whose members encouraged him to fight for his beliefs. In their reference to the cheap price paid for Manhattan, the occupiers were offering $1.24 per acre for Alcatraz, more than twice the price California Indians were receiving from the government for land. While the Proclamation does not provide details of that negotiated settlement in California, Richard Oakes’ wife Annie Marufo was a Pomo, and another Pomo/Modoc from northern California, Luwana Quitiquit, was a part of the occupation. Oakes would also go help the Pit River Indians try to reclaim tribal land in Northern California from the Pacific Gas & Electric company.

A journey of healing:

Consider how this Proclamation represents a response to perceived injustice, and how taking action can lead to healing. While not perfect (women did not have an equal role and a child died), this political action drew international attention to American Indian struggles and positive steps to build a healthier, more equitable society that honored tribal legacies, and a future characterized by peace and justice. It was a call for civil and human rights. It would start the ball rolling toward the building of Native American Studies programs at colleges and universities, new tribally-run colleges and universities would come into being, tribes would build their own museums, and awareness of Native contributions to the field of ecology/environmentalism would skyrocket. The articulation of this Proclamation, with input from members of many tribes, contributed to a feeling of a shared history and solidarity for facing the future.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

1) Additional Primary Sources

“Alcatraz Indian Occupation Records,” 1964–1971, San Francisco Public Library. The finding aid details the contents of the four cartons and one box (4.5 cubic feet) that the library holds. This was a donation from Frederic S. Baker, the legal representative of Indians of All Tribes, Inc., made to the library in June 1972.

Video footage on YouTube, made by Doris Purdy (whose mother was a Sioux), shows American Indians arriving by boat to Alcatraz and spending time there, drumming, dancing, making meals.

Pacifica Radio Archives, audio file, “Alcatraz panel with Native Americans from various tribes“ (1969). Radio journalist John Trudell was broadcasting from the island in December 1969.

“The Letter“ (December 16, 1969), written by IAT from the island. The letter comes toward the bottom of this web page, which also reproduces a transcript of the Proclamation and provides an introduction that helped with our introduction, above.

Video footage from Alcatraz (7 minutes), shows Richard Oakes delivering the Alcatraz Proclamation in 1969. Published by National Public Radio, 2017.

A photo, date unknown, shows the water town with “Indian Land” painted on it. Another photo from the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, with “You are on Indian Land.” Red Power is mentioned in the graffiti in this photo, which also shows the Navajo greeting, “Yata-hey!” In this teaching unit, you will find several photos, such one of a sign referring to the “Dept. of Indian Bureau of White Affairs,” turning on its head the idea of the interfering Bureau of Indian Affairs, alongside a photo of LaNada Boyer next to the graffiti, “Custer had it coming.”

Alcatraz Indians of All Tribes Newsletter. Two issues (vol. I, nos. 1 and 2, January and February 1920) are held at the Wisconsin Historical Society Library. There were two additional issues, but the library does not have these.

Ben Winton, “Alcatraz, Indian Land,” published originally in the Native Peoples Magazine, Fall 1999.

2) Secondary Sources

Bacon, John, “Escape from Alcatraz: Letter Claiming Inmates Survived ‘Inconclusive’,” USA Today, January 25, 2018.

Blansett, Kent. A Journey to Freedom: Richard Oakes, Alcatraz, and the Red Power Movement. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

Deloria Jr., Vine, Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, 1969. This asked for greater balance in the U.S. history of western expansion, exposing abuses of settler colonialism toward Native Americans. Note how this book came out the same year as the occupation of Alcatraz.

Fortunate Eagle, Adam, Alcatraz! Alcatraz!: The Indian Occupation of 1969–1971. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 1992.

Fortunate Eagle, Adam, and Tim Findley, Heart of the Rock: The Indian Invasion of Alcatraz. Norman: Univerity of Oklahoma Press, 2014. Adam Fortunate Eagle (also known as Adam Nordwall) was a part of the invasion of Alcatraz in late 1969.

Johnson, Troy R., The American Indian Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Red Power and Self-Determination. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008.

Smith, Sherry L. Hippies, Indians, and the Fight for Red Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Spalding, David, ed., At Large: Ai Weisei on Alcatraz. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2015.

Westbrook, Tina, ed., Letters from Alcatraz: Forty Years Later. Bloomington: Trafford Publishing, 2010.

3) Additional Teaching Materials

“Alcatraz is Not An Island: The American Indian Movement,” a two-page publication followed by study questions, grade and author not indicated.

“The Alcatraz Occupation: Does a Protest’s Success Affect its ‘Americanism’?” grade and author not indicated.

“The Alcatraz Proclamation: A Primary Document Activity,” for grades 6–8 and 9–12. Published by Teaching Tolerance, n.d.

“Islands—Alcatraz Occupation,” for high schools. Published by the Oakland Museum, California.

“Understanding and Analyzing Iconic Non-Fiction Texts of the Civil Rights Movement,” grade and author not indicated. Published by the Annenberg Lerner, 2015.

4) Documentaries

The Occupation of Alcatraz that Sparked an American Revolution is an 8-minute documentary on YouTube, hosted by Seeker VR, and published in 2017. This film includes a Sunrise Ceremony with drumming and dancing on the island. LaNada War Jack (Shoshone/Bannock), formerly LaNada Boyer, brings the Alcatraz fight up to the recent Standing Rock Sioux action against the pipeline.

We Hold the Rock: The Indian Occupation of Alcatraz is a 26-minute video documentary on YouTube, hosted by the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and published in 2014. It includes interviews with Adam Fortunate Eagle (one of the organizers of the occupation), Wilma Mankiller (formerly the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation), Vine Deloria, Jr. (historian and activist), Dr. LaNada War Jack (Shoshone/Bannock), Shirley Guevara, and Edward Willie, among others. This video also includes a reading of the Proclamation.

“’Yata-hey, Navajo greeting with Rain Cloud’

“’Yata-hey, Navajo greeting with Rain Cloud’

Golden Gate National Recreation Area”

(photo credit: National Park Service)