Note: I will be out of town this week. Postings will be limited to nonexistent.

Last week I said that the Fed’s new strategy guidance, particularly the adoption of the average inflation target, was clearly written by a committee as it can mean whatever a particular FOMC participant wants it to mean. Early comments by Fed officials reinforce this observation. Via Jonnelle Marte and Howard Schneider at Reuters

A day after rolling out a new strategy for U.S. monetary policy, Federal Reserve officials on Friday diverged over what it might mean in practice, saying there is no exact formula for the average inflation rate they plan to target.

The new policy might mean 2.25% is acceptable. Or 2.5%. Or it depends on the speed inflation is changing. One thing it doesn’t depend on is any quantification of “average.” I guess R doesn’t do averages? Cleveland Federal Reserve President Loretta Mester sums up the situation:

Recognizing when inflation has risen too much will depend on what else is happening with the economy, Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said. “This isn’t really tied to a formula,” Mester said in an interview with CNBC, nodding to Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s speech on Thursday in which he laid out the new strategy. “It’s really going to depend on what’s going on with the economy and how stable your inflation expectations are.”

The new strategy is really about increasing the Fed’s policy flexibility. It’s not “average inflation targeting.” The Fed removed the “average” from “average inflation targeting” because the average would become a rule and the Fed wants less rules, not more. Marte and Shneider provide a nice framing:

The comments by the Fed policymakers reflected, in part, the longer-term thinking behind the strategy document, crafted not to bind decisions at individual Fed policy meetings but to frame how the central bank is setting priorities.

The previous guidance constrained the Fed, or so they believed, to setting policy to return to the 2% target without overshooting that target. The Fed wanted flexibility to overshoot by some degree. Calling the new policy “average inflation targeting” allows the Fed to overshoot by some undefined measure. That’s all “average inflation targeting” does for the Fed. Beyond that, the strategy updates effectively alter the Fed’s reaction function to be more responsive to maximizing employment while less responsive to Phillips Curve-based inflation forecasts.

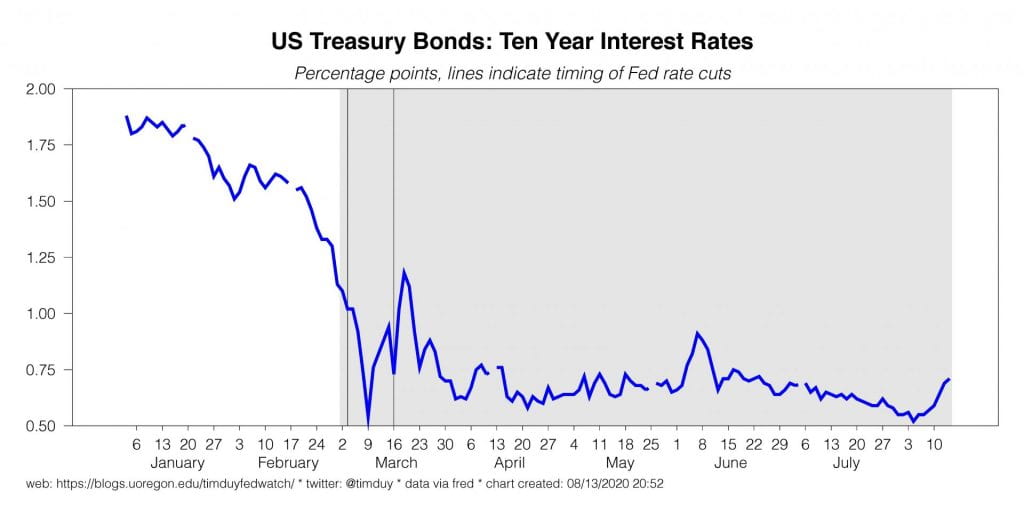

From a practical perspective, the Fed simply updated its guidance last week to match how they were already setting policy or signaling they were going to set policy: They intended to maintain very accommodative conditions until inflationary pressure were clearly evident in the data not just the forecast. Note that the variety of opinions about the exact policy implications indicates that the Fed is not yet prepared to offer additional guidance or policies intended to accelerate the expansion. That enhanced forward guidance doesn’t feel like it is coming in September.

The Fed might not offer updated guidance if the data flow continues to improve. To be sure, the Fed doesn’t appear to believe the recovery is sustainable or that unemployment will recede in any acceptable timeframe, but they don’t seem to have a consensus about any additional policy response. If the economy does in fact sustain a relatively robust pace of improvement, they might not have to issue updated guidance. And “robust” doesn’t have to mean the post-lockdown jump in the data flow; it just needs to be something reasonably better than expectations.

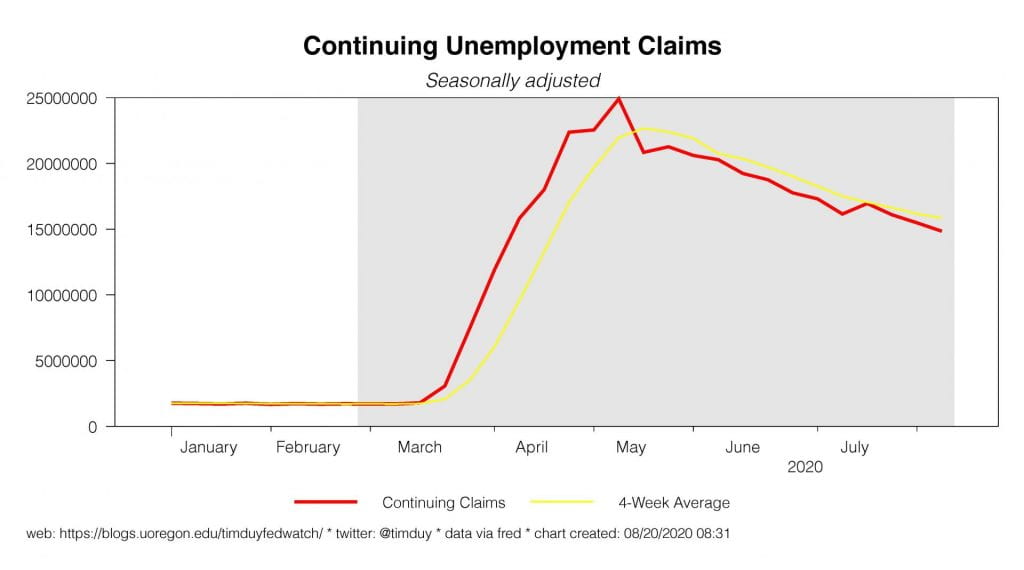

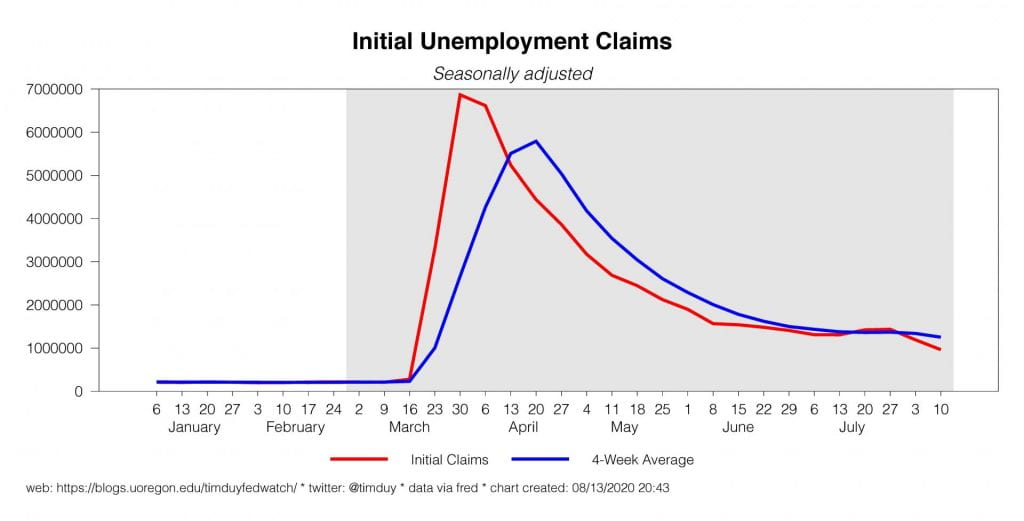

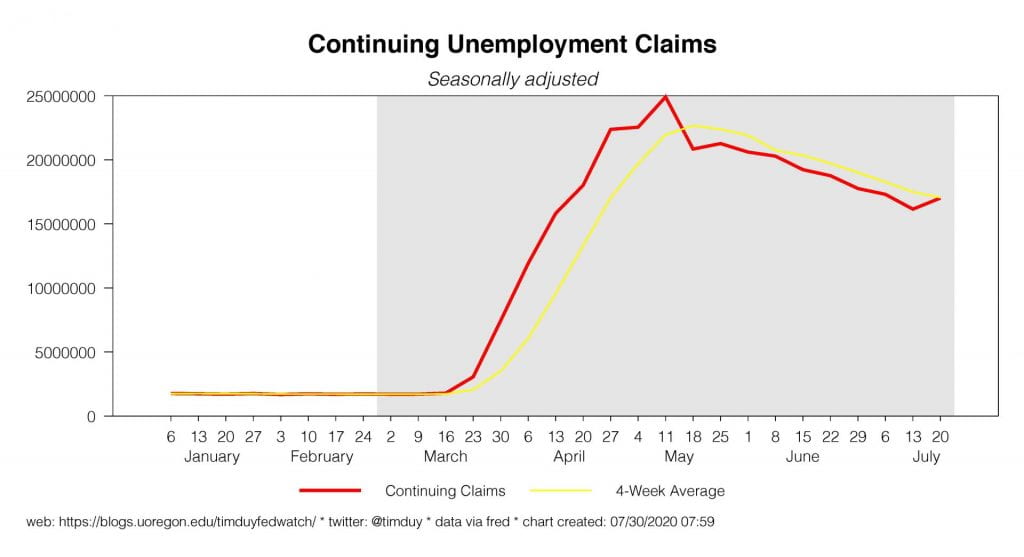

Initial and continuing unemployment claims continued their slow descent:

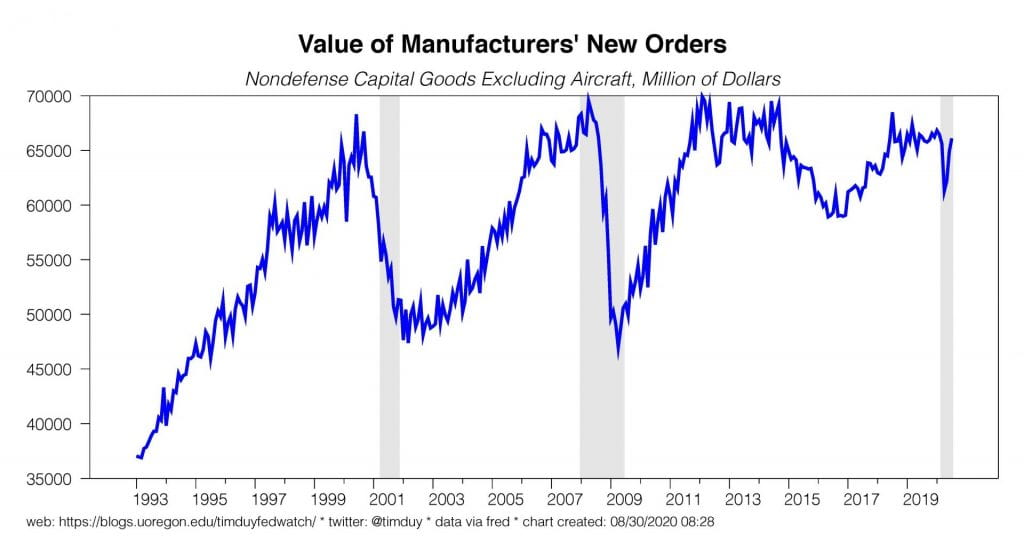

Still a glass half-empty or half-full situation. Too high, but moving in the right direction. Something that is becoming more like a full-glass situation is the manufacturing sector. New orders for capital goods are making a V-shaped recovery:

The initial decline was less steep and recovery more rapid than the 2015-16 period. This dynamic I suspect can be attributable to the very under-appreciated fact that as of February of this year, there was nothing wrong in the U.S. economy from a macroeconomic perspective. There was no bubble or misallocation of activity of any consequence that needed to be addressed. This was true even in the now beleaguered oil and gas sector that worked off its excess in the 2015-16 downturn:

Also note the V-shaped recovery developing in consumer durable goods order:

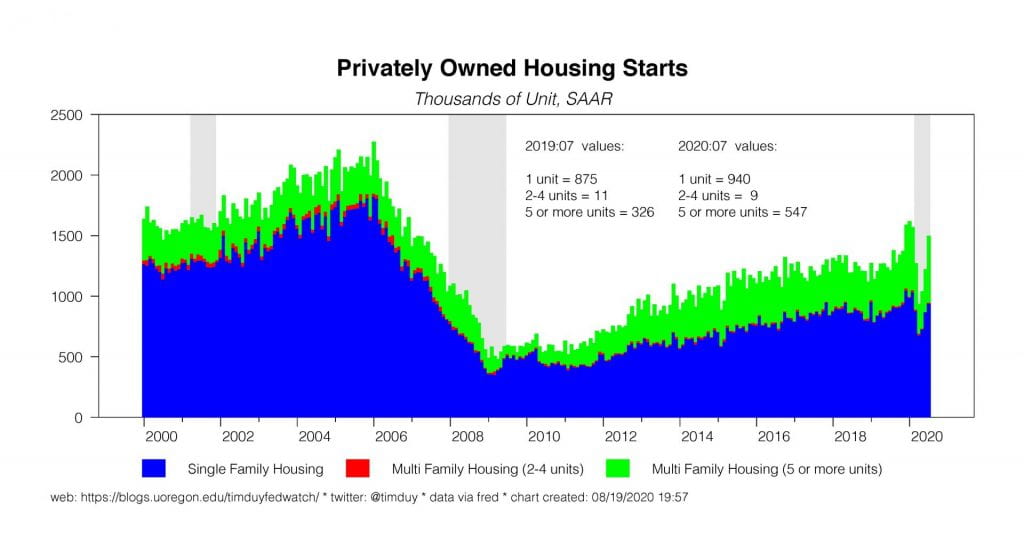

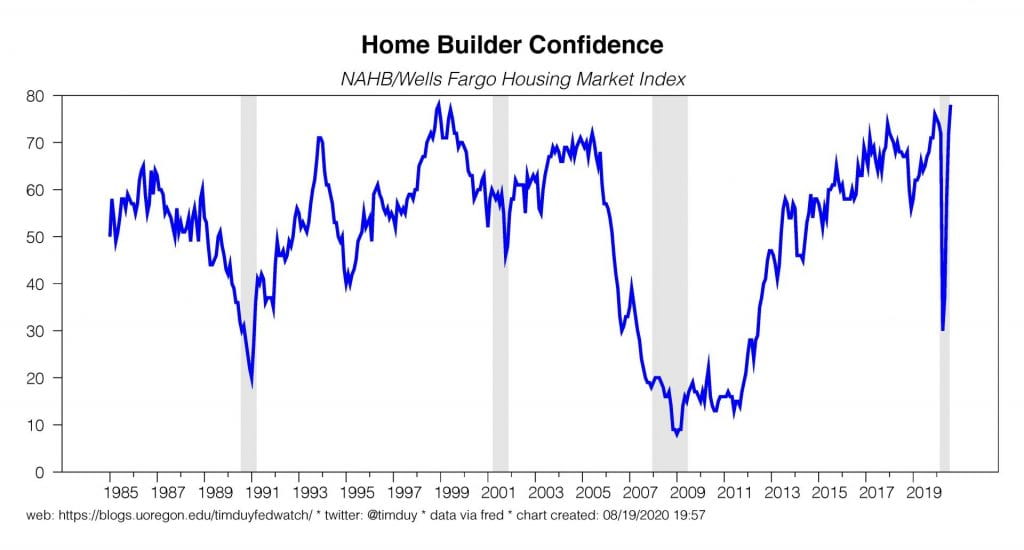

The strong housing market suggests this trend will continuing. New homes need new appliances and new existing purchases also need new appliances. Housing is being supported by very strong underlying demographics. Ignore at your own risk.

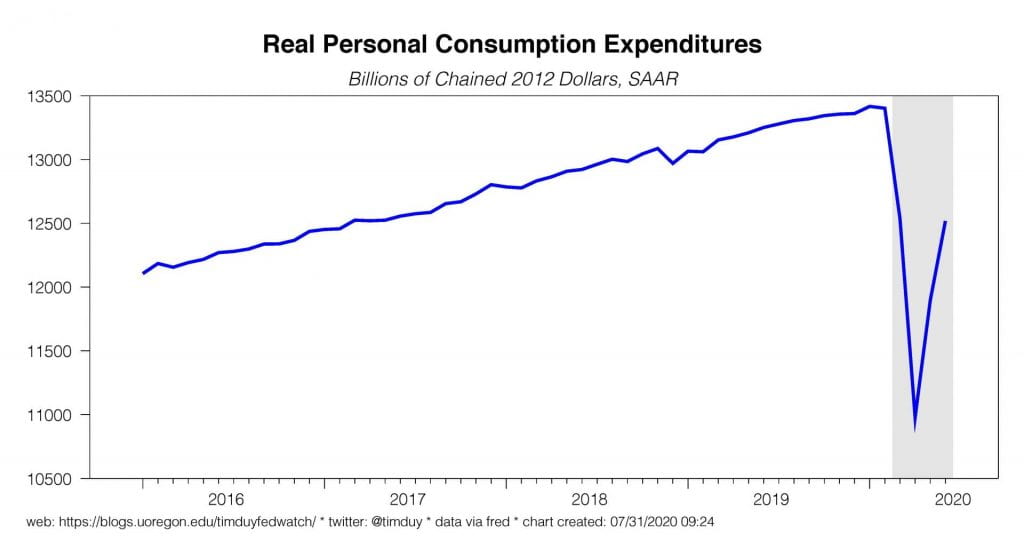

Consumer spending growth slowed:

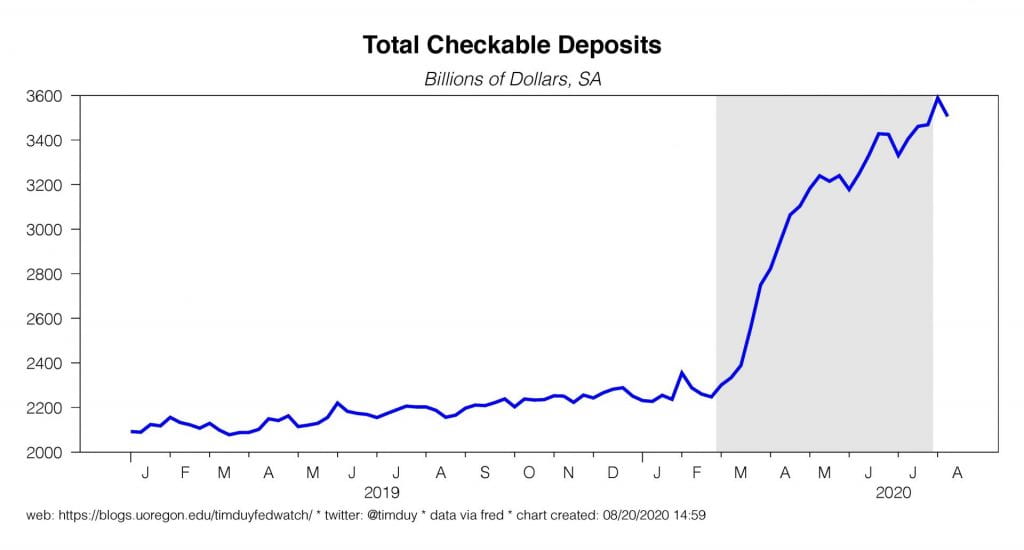

The are reasonable concerns about the sustainability of consumer spending considering that the $600 enhanced unemployment benefits have ended. I would suggest that you balanced these concerns against the possibility that this loss is offset by job gains and that large portions of the stimulus were still funneling into savings as of July:

The are reasonable concerns about the sustainability of consumer spending considering that the $600 enhanced unemployment benefits have ended. I would suggest that you balanced these concerns against the possibility that this loss is offset by job gains and that large portions of the stimulus were still funneling into savings as of July:

Household finances in aggregate continue to improve:

I suppose there could be a permanent increase in savings so this is not technically “excess.” I suppose too that pigs might fly. Seriously, American consumers are not known for their frugality. I think a wave of spending will hit the economy next year.

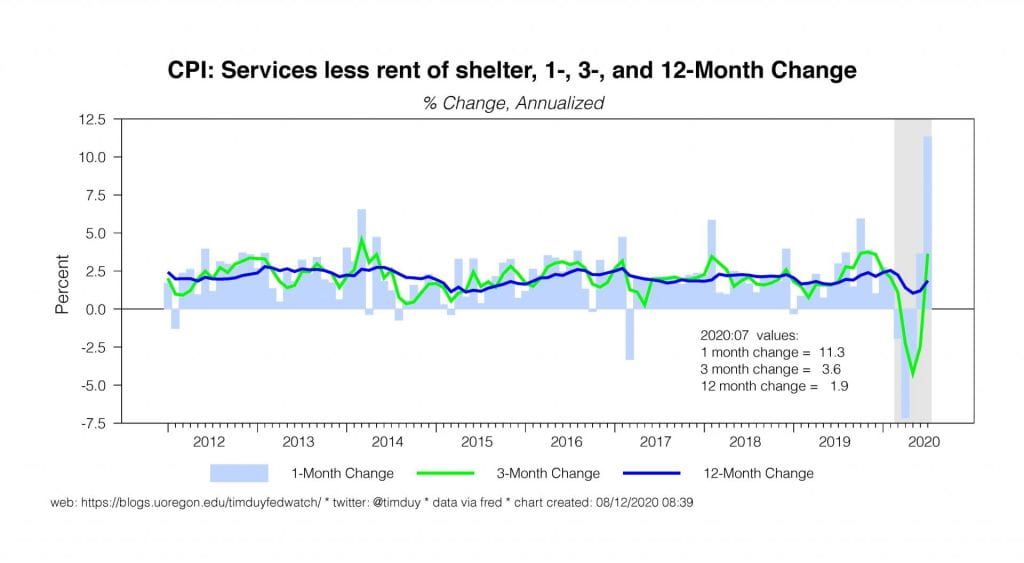

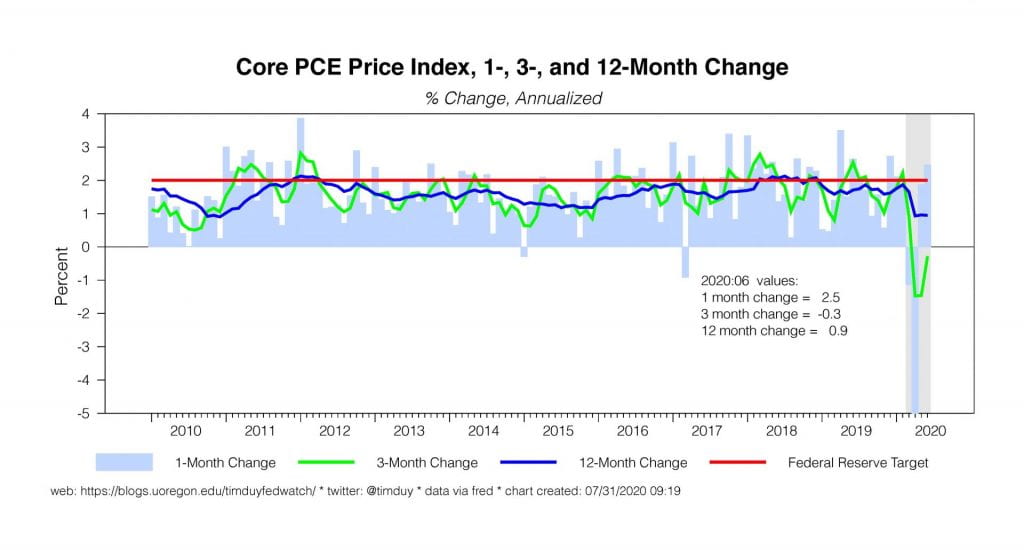

On a final note, Michigan consumer sentiment still hovers at pandemic lows. Inflation expectations, however, remain firm:

Something to keep an eye on if supply chains are still constricted and labor supply challenged by lack of access to child care if that wave of spending hits next year.

Bottom Line: It has become clearer that the Fed’s updated strategy, while important, really just formalizes the direction the Fed was already taking. What it does not do is create new constraints for the Fed; I think we should all come to terms with the reality that this is not really “average inflation targeting” even if we will have to keep calling it by that name. Watch the data flow and just at least be open to the possibility that there are upside risks to the outlook.