The day of reckoning for the Fed may soon be at hand. With the yield curve continuing to flatten and the 10-2 spread falling to a meager 33 basis points this week, an inversion before the end of the year is not out of the question. At that point, the Fed will need to choose between sticking with their current rate path or heeding the recession warning of the yield curve and pausing or perhaps even cutting. The latter option could send stocks higher while recession lurks behind the former.

Money flew to the safe haven of U.S. treasuries this week as investors weighed the potential impact of trade wars and shied away from stumbling emerging markets. With the Fed still signaling further rate hikes, the weight of these flows fell on the long end of the yield curve instead, pulling down the gap in rates between 10 and 2 year treasuries to just 33 basis points.

The flattening of the yield curve by itself does not necessarily indicate trouble ahead. It’s inversion (a negative spread) or nothing when it comes to using the curve as a recession signal. But we are moving closer to an inversion, close enough that an inversion this year cannot be ruled out.

How will the Fed react to a yield curve inversion? They can heed its warning as arguably the most reliable recession indicator or decide this time is different. If this time is not different and the yield curve signals recession in the making as in the past, then continuing rate hikes would be a clear policy error that would tip the economy into recession. Undoubtedly, that recession would weigh on earnings and by extension equity prices. And tripping the economy into recession would likely put monetary policy back into unconventional territory as the Fed’s interest rate tool lacks the 500 basis points needed to address a recession.

Alternatively, the Fed could shift to a wait and see mode if the yield curve inverts. As I argued this week, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell does not appear sufficiently concerned about inflation to keep hiking rates if the economy stumbled or was threatened by financial unrest. That’s would be good news for stocks. Recall that the stock market soared after the Fed stopped hiking rates in 1995 after a flat 1994. Taking a recession off the table would almost certainly support expectations of higher future earnings.

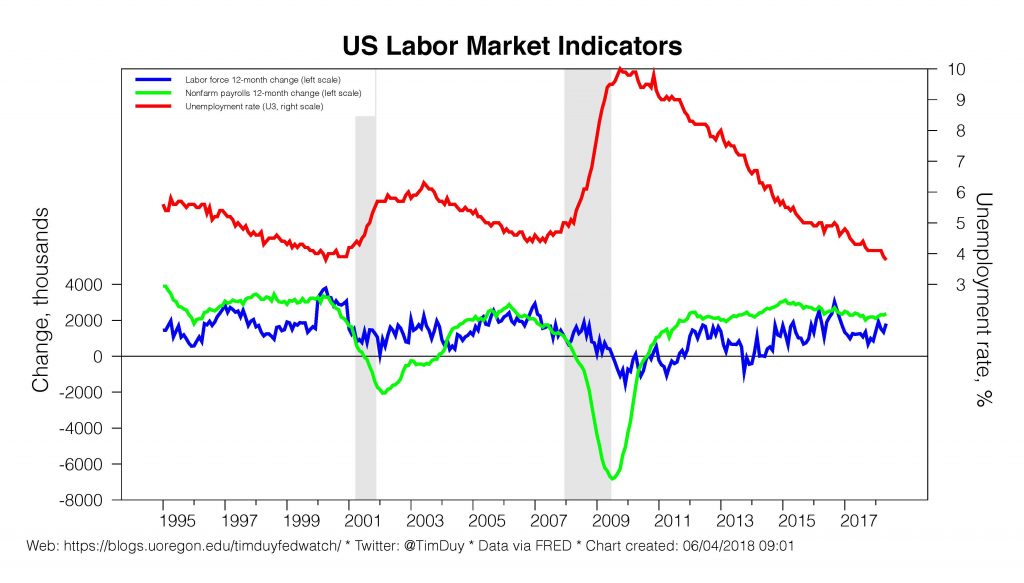

But which choice will Powell & Co. make? It is not clear that central bankers would see an inverted yield curve as a sufficient threat to the recovery to revisit their rate hike plans. Importantly, consider the current economic environment. In the second quarter, growth might exceed 4 percent at a time when the unemployment rate is already 3.8 percent. Even with inflation low and stable, there will be enormous pressure on the Fed to keep hiking rates even if the yield curve were to invert.

With this economy, what prompts the Fed to react to an inverted yield curve? A clear and convincing threat like that posed by the Asian Financial Crisis. If the inversion results from a sharp drop in long yields driven by such a substantial financial market disruption, the Fed will likely react.

But absent a financial market disruption, the Fed may rely on the argument that the yield curve is inverting at a low level of rates due to a low term premium and as such policy is not really as tight as it may seem. In other words, nothing to see here, folks.

Bottom Line: It may indeed be true that this time is different. Still, given the yield curve’s track record in past cycles, the Fed ignoring an inverted curve at the 10-2 horizon and pushing ahead with rate hikes would put me on recession watch. That recession though would still likely not emerge until another year or more passed after the inversion.