If You Don’t Have Any Time This Morning

The Fed will cut interest rates at least 25bp in September. This week, in Jackson Hole, Powell will hopefully define a path toward that rate cut and subsequent cuts as he seeks to sustain the expansion.

Newsletter version!

Key Data

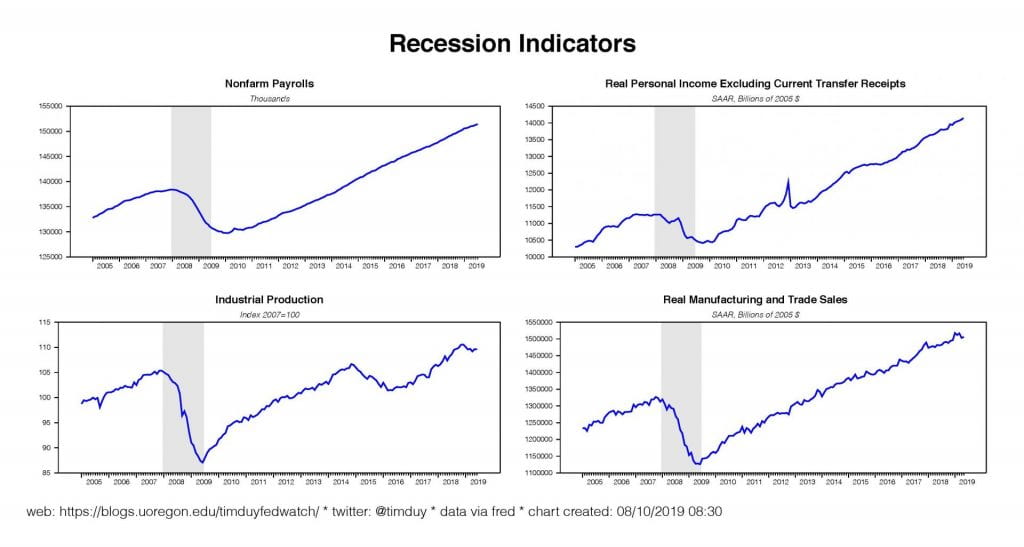

A fairly busy past week for data revealed a solid yet unspectacular pattern of economic activity.It’s fairly clear that the manufacturing sector is weak at the moment. Industrial production is basically flat compared to a year ago; at the end of last year, the nation’s manufacturing activity was growing at a greater than 5% annual pace. Still – and importantly – the slowdown in the sector has yet to match that of 2015-16 nor does it even approach something consistent with a recession. I have said this before, but it should be said again: As manufacturing becomes a smaller portion of the economy, we should expect more instances of manufacturing downturns or even manufacturing recessions being separate from the overall business cycle.

In contrast, the much larger consumer sector of the economy continues to power forward. Retail sales sustained the rebound from turn-of-the-year weakness and core sales are again growing at a roughly 5% year-over-year rate, actually a bit higher than seen during the 2015-16 slowdown. The general continued strength in spending reflects the solid labor market. In my opinion, job losses need to mount before consumer spending will crumble. Low and steady initial unemployment claims indicate that those job losses are not yet on the horizon.

That said, University of Michigan consumer sentimentslipped to a seven-month low. Respondents reacted negatively to the Trump administration’s escalation of the trade wars. Between that and a reported negative reaction to the Fed’s interest rate cut, the report concluded that “is likely that consumers will reduce their pace of spending while keeping the economy out of recession at least through mid 2020.” I would be wary that any reported nervousness among consumers will have a persistent impact on spending barring job losses. It is easier to say that you will change your spending behavior than to actually change your behavior without a major life event to force that change.

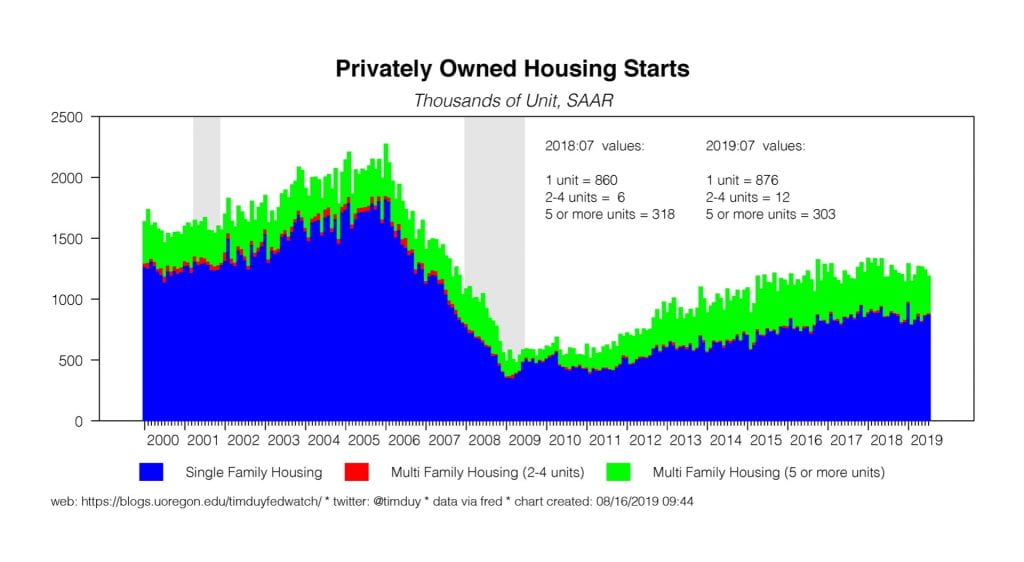

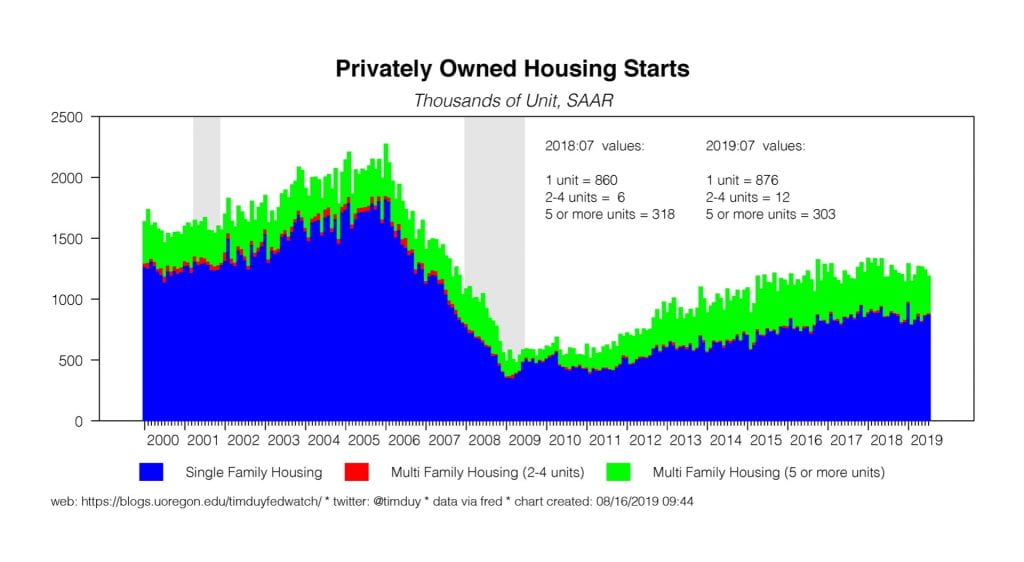

Single-family housing starts rose in July although the multi-family sector pulled down the overall numbers. Single-family starts have largely recovered from the decline in the latter half of last year; lower interest rates had a positive impact on the sector as should be expected. Also note that although overall starts were down, permits were up. While I don’t think that housing will offer much if any positive contribution to overall investment spending, it also clearly is not falling apart as one might expect ahead of a recession.

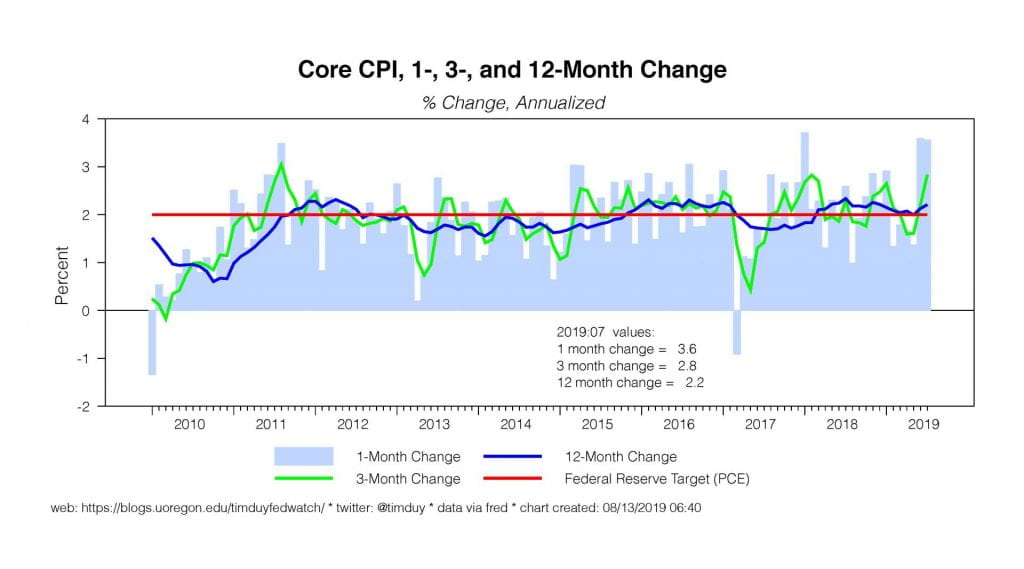

Inflation came in hot; see my remarks here.

Fedspeak

Not much Fedspeak last week as might be expected given the upcoming annual Jackson Hole conference. Still a couple of Fed presidents made the news.

Even though he doesn’t see an expansion, Minneapolis Federal Reserve President Neel Kashkari argued for further policy easing, saying that “[it] is better to be early and aggressive if you see a slowdown than wait until you’re sure the economy is in recession.” Kashkari also supported currently-embattled Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell while throwing shade on President Trump (via Bloomberg):

“Jerome Powell is an outstanding Federal Reserve chairman and an A-plus public servant and I think we’re all lucky to have him and I completely support him,” Kashkari said. “Very few businesses that I talk to are pointing to the Federal Reserve and saying ‘hey, it’s your interest rate policy that’s slowing things down.’ Much more likely it’s focused on trade policy and global uncertainty,” he said.

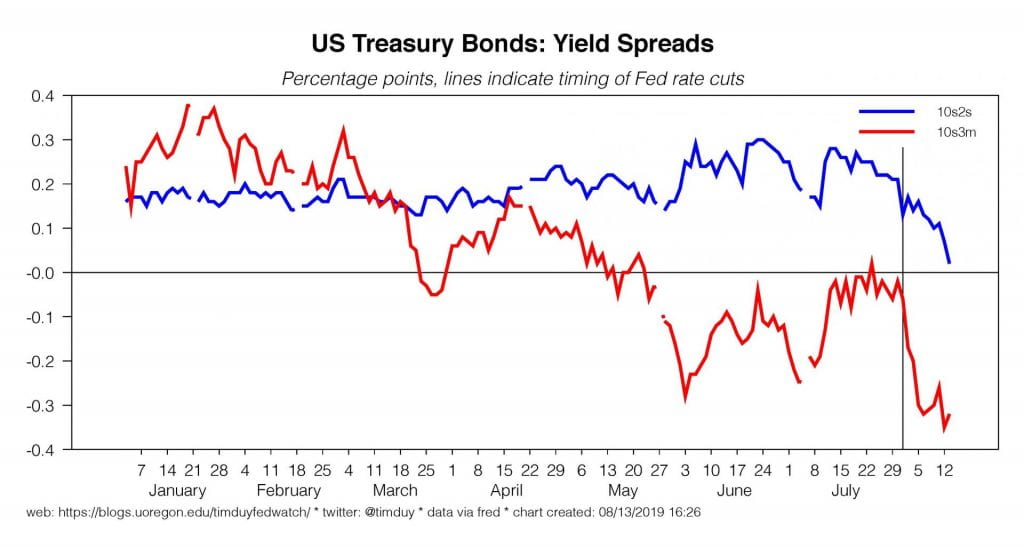

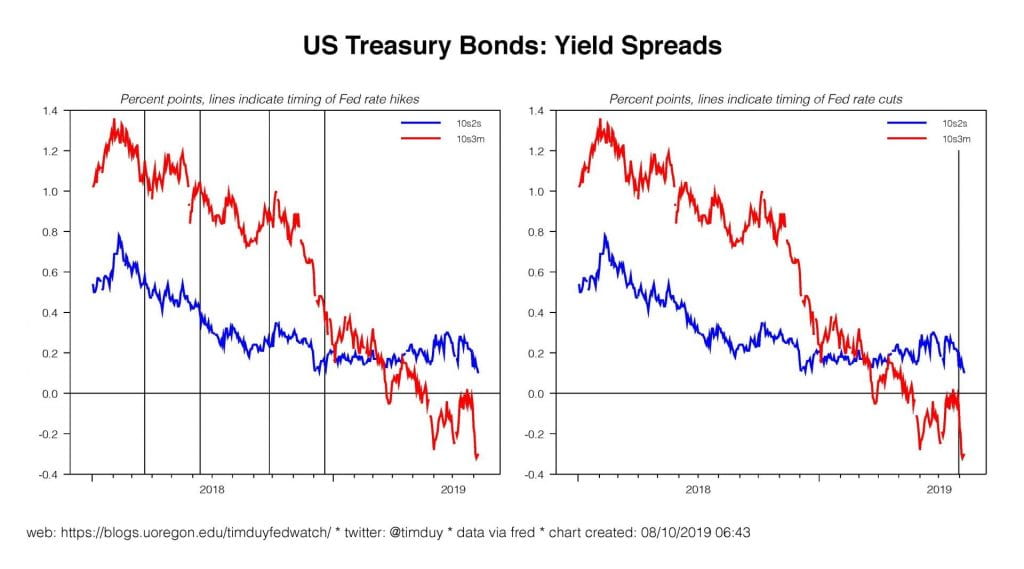

St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard was more cautious in his policy prediction (interview here). Bullard viewed the data as solid and was not particularly concerned about the yield curve inversion. Via Bloomberg:

“Any inversion that is going to send a bearish signal for the U.S. economy would have to be sustained over a period of time, so we are going to have to wait and see on that,’’ Bullard said. “You have got this flight to safety going on’’ with foreign investors seeking the perceived sanctuary, and positive yields, of U.S. bonds.

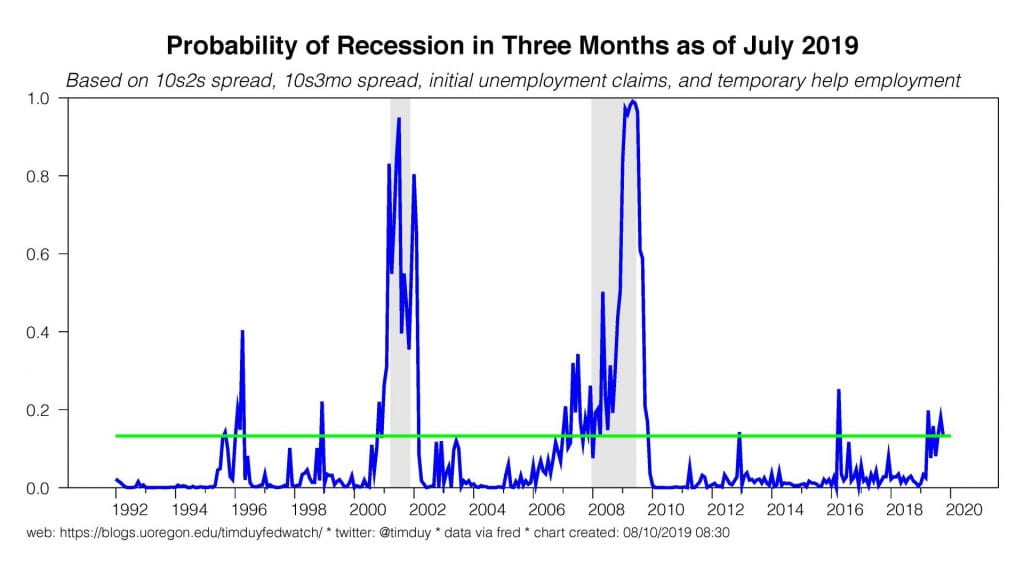

Recall that Bullard has long expressed concerns about the yield curve – see back as far December 2017. Now though that the inversion is upon us, it’s all about it needs to be “sustained” and “wait and see.” The “sustained” part is interesting; the 3m10s portion of the curve first inverted in January, so it has already been sustained, so what’s Bullard waiting for? I would say Bullard is acting as someone might if they don’t really understand the flow of the data. The yield curve is a long-leading indicator; it will first come when the data is solid, as it is now (see me here). Because the data is solid, you get cold feet about reacting to the yield curve. But if you wait to act on the yield curve, as Bullard suggests, it will be too late to prevent a recession. You might as well not have indicated any concern about the yield curve in the first place.

In any event, Bullard will fall in line with the rate cut that is coming in September; he also made clear his concerns about declining market-based inflation expectations.

Upcoming Data

Slow data week. The highlights are existing home sales (Wednesday), Kansas City Fed manufacturing survey (Thursday), the usual initial unemployment claims report (also Thursday), and new home sales (Friday). The most important event on the calendar is Powell’s Jackson Hole speech on Friday.

Discussion

The Fed is going to cut interest rates in September, even if they as of yet don’t want to admit it. That said, I don’t think they have a unified framework to justify and explain a rate cut and the lack of such a framework makes for a challenging communications situation.One description of Powell’s last press conference was that the rate cut was dressed-up in a “coat of many colors” to gain consensus for the action. It would be helpful for Powell to provide a more consistent policy vision with this week’s speech, “Challenges for Monetary Policy.”

As of last Friday, 30-year treasury rates were less than 1-month rates. That’s not exactly a healthy look for an economy that is supposedly “solid.” Not that the bond markets had much good news to begin with; the 3m10s inversion intensified this week and the 2s10s spread even briefly inverted. In my opinion these things are warning signs that monetary policy is too tight and will eventually crimp economic growth severely.

I think the Fed currently hesitates to embrace such an analysis. It sounds too much like they are taking marching orders from the bond markets;they typically like to place their actions within context of their policy framework. That framework, however, feels like it has fallen apart in the last six months. A critical part of that framework, the Phillips curve, is essentially on the back burner now that the relationship between unemployment and inflation looks relatively weak.

Downgrading the Phillips curve allowed the Fed to downplay the need for any further rate hikes. But there has yet to be a consistent story to justify the last rate cut, let alone more cuts. Powell pieced together a consensus for the last rate cut on the back of weak global growth, trade policy uncertainty weighing on business investment, muted inflationary pressures, lower r-star, lower estimates of the natural rate of unemployment, and the importance of sustaining low unemployment for as long as possible. Something for everyone. A coat of many colors.

It’s not clear that this will work to justify the three or more additional rate cuts market participants anticipate the Fed will deliver. The one thing that everyone can agree on to justify that magnitude of cuts would be significant concerns of imminent recession. But that’s not in the data and by the time it is in the data the recession will be on top of us. It would be too late to avoid a recession at that point.

If, as it increasingly appears, that Powell’s primary focus is on avoiding recession given that inflation has been persistently below target and hence not a threat, I think he will be seeking to create a path forward that defines a framework to justify multiple rate cuts and can be broadly supported by the rest of the FOMC.

In my perspective, it would be fairly straightforward to lean on the natural rate of interest to centralize an argument for further easing.The basic story would be that the Fed wants to sustain the current near-trend pace of growth and to do so they need to ensure that policy is not restrictive. But falling U.S. interest rates consistent with slowing global growth, low global interest rates, low inflation, and business confidence uncertainty, indicate that the neutral rate of interest, at least in the short-term, has fallen. This in turn leaves U.S. policy rates too high and likely even restrictive. You won’t see this in the data today, which reflects the level of monetary accommodation 6-12 months ago. You will see it, however, in 6-12 months unless the Fed adjusts policy rates accordingly. Hence, the Fed needs cutting interest rates in the months ahead to ensure that policy is sufficiently accommodative to sustain the expansion. Absent such accommodation, the economy will be excessively vulnerable to negative shocks such as trade policy uncertainty.

That said, this is pure speculation on my part. At a minimum, I expect that Powell’s will make clear that the Fed’s primary goal is to sustain the expansion. This will be viewed as verifying market expectations for substantial rate cuts in the next year. My read on the data and the yield curve is that the Fed can accomplish the soft landing and avoid a return to the zero-lower bound, but they first need to soon accept this requires them to cut another 50bp to 75bp.

Bottom Line: The Fed will need to cut rates next month even if they don’t yet know it. The faster they coalesce around the need for multiple rate cuts, the more likely it is that they will steer the economy away from recession.