The Fed speak has been a tad cacophonous this week. Let’s try to cut through the noise.

Here is a trick learned from many years in the backcountry: When you lose your trail, stop and backtrack to the last place you know where you were. Then start over. In this case, the starting point is the Fed guidance that operationalizes the update strategy:

The Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time.

There are three conditions for a rate hike: Maximum employment, inflation at 2%, and the expectation that inflation will exceed 2% for some an undefined period. There is a lot of guidance there, but a lot that is left unsaid. We don’t know what inflation would be “moderately” in excess if 2 percent. We don’t know how long the Fed expects inflation to exceed 2 percent. We don’t know even what the Fed will eventually conclude is maximum employment even if we believe that it is something below 4% unemployment.

It’s not just that we don’t know these details. FOMC participants don’t know these details. They have different views of the appropriate interpretation of the guidance. Chicago Federal Reserve President Charles Evans, for example, admits that his willingness to tolerate 2.5% is a minority view of the implementation. They also have different views of when these conditions will be met. Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren acknowledges that he is particularly pessimistic, saying we would be lucky to reach 2% inflation in 4 years.

All of that is interesting but really only an intellectual exercise. They are false trails. The Fed doesn’t believe they need to lock down any details on an “exit strategy” because the forecasts of FOMC participants indicate that rates will remain at near-zero levels through at least 2023. And that is assuming we get the additional fiscal stimulus that they are pleading for.

Vice Chair Richard Clarida tried to clarify the Fed’s position, telling Bloomberg that the Fed would need to see months of observed inflation at 2% before the Fed would even think about raising interest rates. I would pay attention to Clarida and not get tied up in the forecasts of Fed presidents. Take the FOMC statement at face value; it’s where you go back to when you are lost. The rate story doesn’t get interesting until inflation is 2% on a year-over-year basis and looks to be sustainable for an extended period of time. I have said this before, but it is worth repeating: The risk is not that the Fed decides to hike rates before inflation hits 2%, the risk is that the economy surprises on the upside and brings that outcome sooner than anticipated.

In hindsight, I guess we should have all seen this confusion coming. Federal Reserve Chair Powell had said that they weren’t even thinking about thinking about thinking about raising interest rates. The updated forward guidance gives guidelines about the timing of a rate hike, so they must be thinking of when to raise rates. The Fed thus inadvertently changed the focus of the conversation.

Changing the focus of the conversation toward rate hike is one communications problem. They still have another problem. They left open the question of the pace of asset purchases. Presumably, they could reduce the pace of asset purchases before inflation hits 2%. Moreover, the Fed made explicit that asset purchases were not just about smooth market functioning, but also providing accommodative financial conditions. The implication is that the Fed has retained the option to reduce financial accommodation before inflation hits 2%, but that reduction comes via a slower pace of asset purchases rather than a rate hike.

See the problem there? I don’t know that market participants have fully absorbed that implication. The focus instead has been on the unwillingness of the Fed to commit to additional asset purchases given that its own forecasts reveal we should expect a long period below target inflation. Oddly, Evans makes the case that additional asset purchases are unwarranted until the economy improves. Via Reuters:

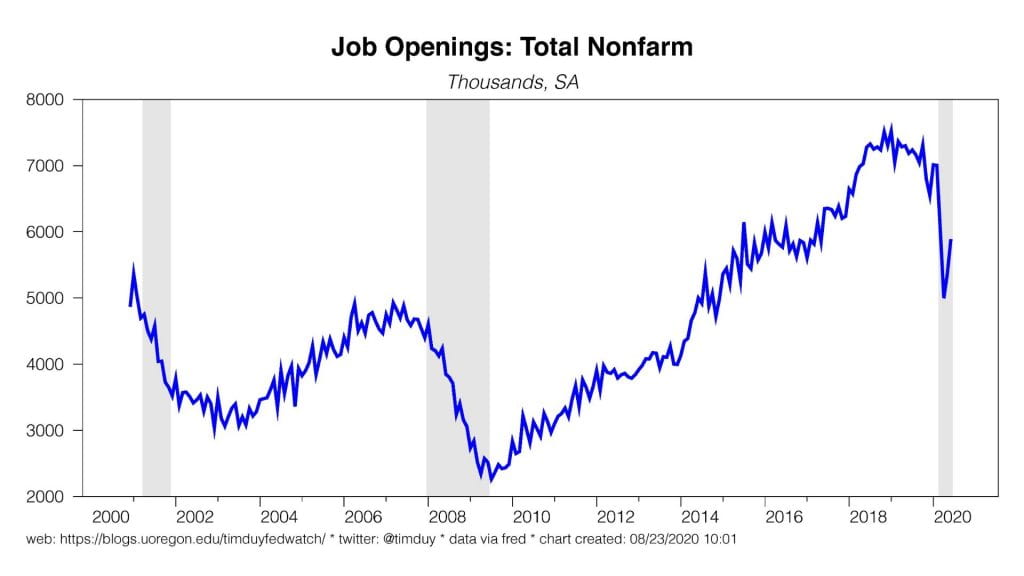

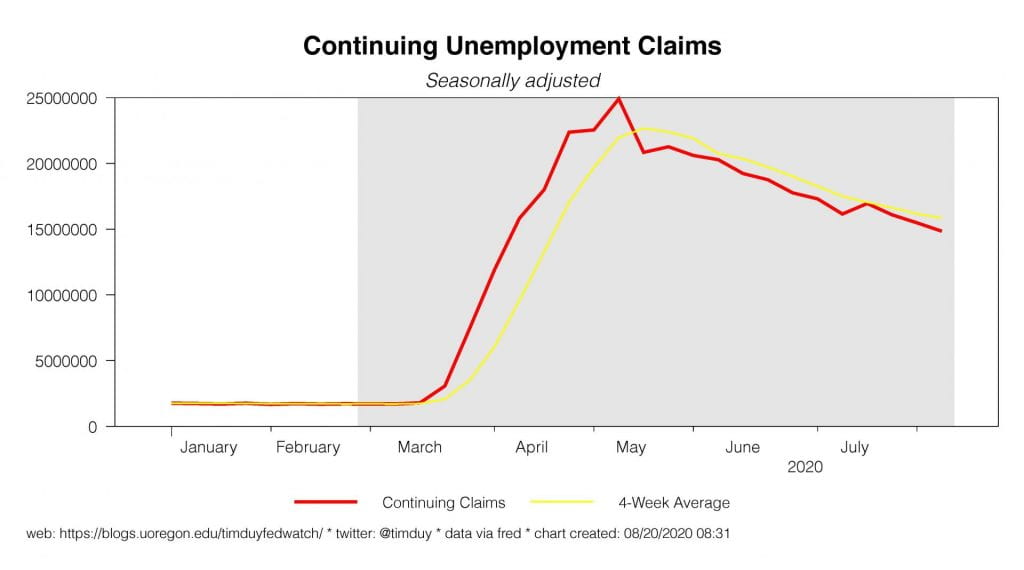

Ramping up the Fed’s bond purchases from their currently monthly pace of $120 billion or otherwise beefing up asset purchases would be premature until the economy gets into better shape, Evans told reporters on a call. That could include unemployment closer to 6% than the 8.4% it is now, and more consumers feeling comfortable spending their money outside of the home.

When that happens, “we would have a better idea of the right amount of accommodation and the way to deliver it,” Evans told reporters. “At the moment everybody understands that we are accommodative.”

That sounds like a “pushing on a string” argument, that policy is no longer effective but could accelerate the recovery when the economy gains some self-sustaining momentum. Personally, I have trouble imagining that Fed will actually boost the size of asset purchases if the unemployment rate falls to 6% and looks to be heading lower, but I guess that is just another academic exercise at this point.

The question for the Fed is have they given too much leeway on asset purchases and even interest rates at this point to avoid having to tighten up the guidance with yield curve control or push out asset purchases along the yield curve. I don’t think they are ready for that yet. I am looking for upward pressure on bond yields that appears unwarranted as something that could push the Fed into a more accommodative stance. That or fading inflation expectations. With that in mind, we should be watching an old favorite:

Bottom Line: The Fed is committed to a near-zero rate policy until inflation reaches 2% and anticipates it will remain at or above 2% on a sustainable basis. That is so far off in the future that we shouldn’t get too deep in the weeds before it happens, but now that the Fed has brought up the issue of rate hikes, they are stuck with a new communications problem. Realistically, every time some Fed president puts some conditionality in the Fed’s commitment, someone like Clarida is going to have to come out and lock down expectations again. If they can’t keep expectations locked down with verbal guidance, they are going to have to resort to yield curve control or asset purchases. Yield curve control is the easy route, but the Fed has dismissed it as an option for now. The real risk for rates is not the Fed’s commitment, but the Fed’s pessimism. If the economy continues to surprise on the upside, Fed forecasts will follow.