Newsletter version!

If You Don’t Have Any Time This Morning

The Fed will cut rates 25bp next week and leave the door open for more. It is reasonable to argue that they need to cut 50bp. If that’s what they should do but won’t, adjust your forecasts down accordingly.

Key Data

The employment report for August 2019 revealed a slowing albeit arguably solid labor market in the U.S.Nonfarm payrolls grew by a somewhat softer than expected 130k, but that number was inflated by the addition of 25k temporary Census workers. Both June and July experienced modest downward revisions. Including Census workers, job gains are running at a 156k average monthly pace over the past three months. Importantly, the pace of gains remains above that which the Fed believes is consistent with steady unemployment. Still, the unemployment rate has been in the 3.6-3.7% range for five months now.

Wage growth surprised on the upside with a 4.8% annualized gain in August; the overall trend is 3.0-3.5% annual wage growth. Hours worked edged up and temporary employment made a solid gain for the month but the overall trend is a weak 1.7k monthly gain on average over the past year. Prime age labor force participation jumped back up; overall participation has basically flatlined since 2016.

One take on the numbers is fairly positive. The economy continues to generate jobs at a pace sufficient to either lower unemployment further or encourage more people to enter the labor force. The jump in wage growth might even suggest that the economy is finally bumping up against full capacity and that is the primary culprit behind slower job growth. And maybe the August jobs number is revised up. Another take is less positive.The job market has clearly slowed, and, after accounting for the Census hires, may have slowed very close to the point where unemployment at best holds steady. That significant downshift in momentum is very worrisome. The second derivative here is not our friend. Moreover, don’t take too much comfort in the stronger wage numbers as that can easily be a lagging variable; wages might not take a hit until unemployment starts rising.

One take on the numbers is fairly positive. The economy continues to generate jobs at a pace sufficient to either lower unemployment further or encourage more people to enter the labor force. The jump in wage growth might even suggest that the economy is finally bumping up against full capacity and that is the primary culprit behind slower job growth. And maybe the August jobs number is revised up. Another take is less positive.The job market has clearly slowed, and, after accounting for the Census hires, may have slowed very close to the point where unemployment at best holds steady. That significant downshift in momentum is very worrisome. The second derivative here is not our friend. Moreover, don’t take too much comfort in the stronger wage numbers as that can easily be a lagging variable; wages might not take a hit until unemployment starts rising.

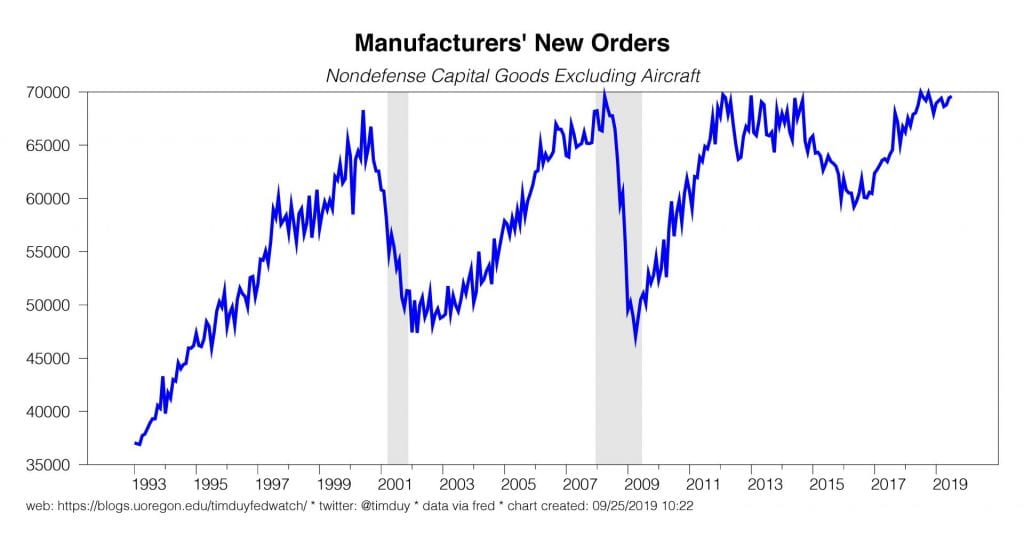

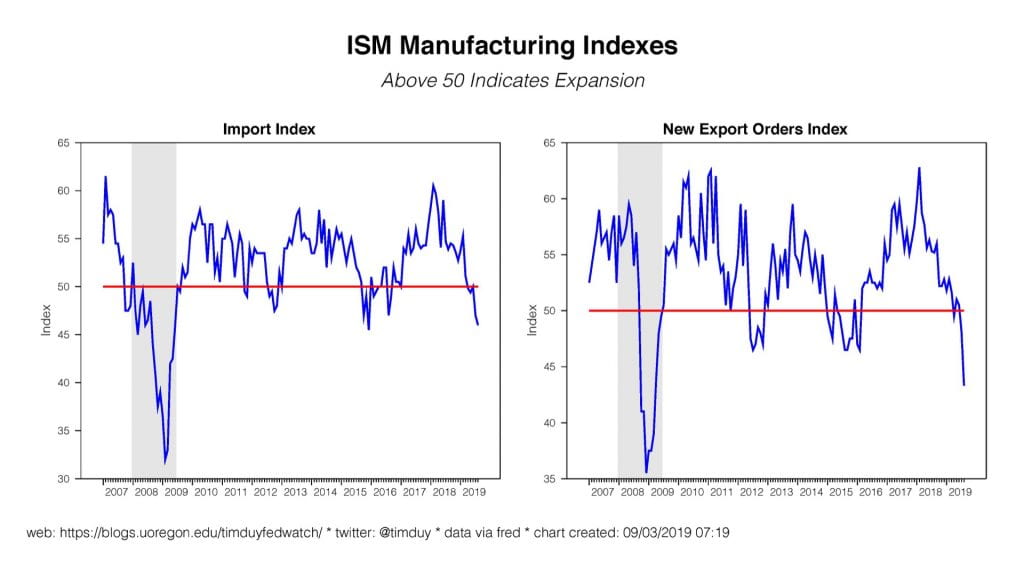

See here for comments on manufacturingfrom last week. Note that GDP tracking measures from the New York and Atlanta Federal Reserve Banks are both at a below trend 1.5% for the third quarter. New York is looking at 1.1% growth for the fourth quarter. Most definitely nothing to write home about.

Fedspeak

Split opinions on the next policy move from policy makers. St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard now wants the Fed to listen to market participants and deliver a 50bp cut at next week’s meeting while his colleague Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren thinks the risks to the forecast need to become reality before further rate cuts are justified. New York Federal Reserve President John Williams argues“[t]he economy is in a good place, but not without risk and uncertainty.” Importantly, he adds this:

An additional fly in the ointment, if you will, is the recently released downward revision for GDP growth covering last year and an announced estimate of a sizable downward revision to payroll employment. One implication of these revisions is that the economy’s underlying momentum was already somewhat less robust than previously thought, even before recent developments pointed to a less rosy outlook.

Last year’s rate hikes, especially December’s, assumed greater economic momentum than was actually the case. Not only that, but whatever momentum the economy had then dissipated more rapidly than expected. That means the Fed needs to both roll back some of last year’s hikes and address the increase in economic uncertainty.

From Switzerland, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell commented on the U.S. economylast Friday. His emphasis on the risks to the outlook reinforced expectations that the Fed would ease at next week’s FOMC meeting.Powell also argued that the outlook for the economy remains favorable because the Fed has shifted the expected path of policy rates downward. An implication of that shift is that the Fed needs to ratify those expectations with lower policy rates or risk an unwanted tightening of financial conditions. Still, he gave an upbeat assessment of the economy, commenting on strong labor markets and taking the positive view on the August employment report. Powell also noted that inflation is heading back to 2%. That fairly positive outlook dashed any hopes that the Fed would cut 50bp at the next meeting.

Federal Reserve economists attempted to quantify the impacts of trade policy uncertaintyon the US and global economies. They estimate that the first and second waves of trade disputes that have hit the economy will slice over 1% off U.S. GDP by 2020. By this argument, trade disputes are not a potential risk for the economy but instead they are already having an impact, further justifying the easing bias taken by Powell & Co.

Upcoming Data

A reasonable amount of data to think about coming this week. JOLTS on Tuesday, PPI on Wednesday, CPI and initial claims on Thursday, and retail sales on Friday. The inflation data is arguably the most important; if the Fed doesn’t fear inflation, then they can hold their dovish bias. The game becomes much more interesting if inflation heads for 2.5% or higher.

Discussion

The Fed is going to cut rates by 25bp at next week’s FOMC meeting and leave the door open for further rate cuts. One could make the argument that the Fed should just get it over with and fix the yield curve with a 50bp cut. I would be inclined to make a 50bp cut to get ahead of any further deterioration in the labor market. The Fed is not so inclined.

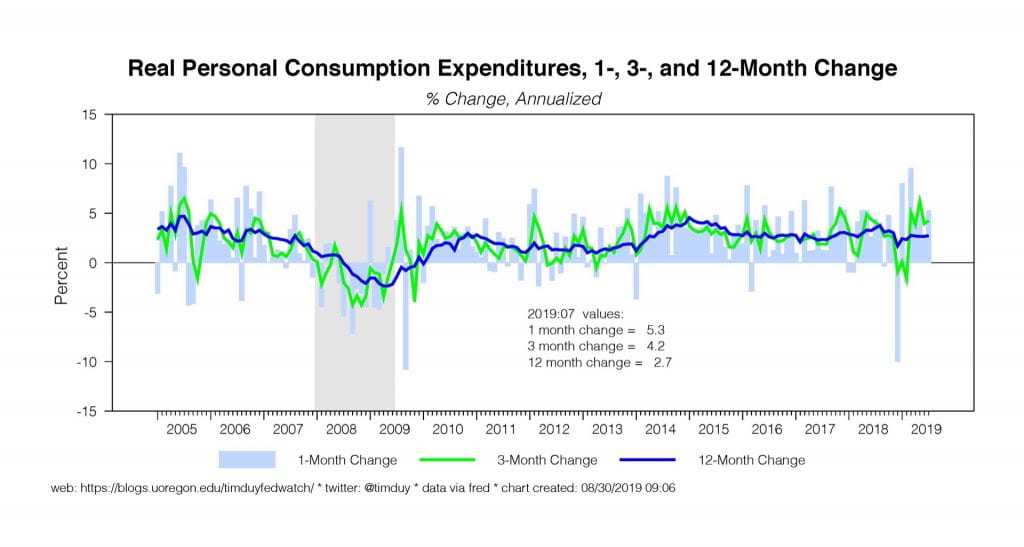

The Fed tends to avoid large rate cuts unless either the data is clearly falling off the cliff or credit markets are seizing up. Neither is currently the case. The data flow remains inconsistent with a recession while the corporate bond market is on fireand U.S. equities could soon see record highs. The Fed will find it difficult to cut rates 50bp in such an environment. Instead, the Fed will take a more cautious approach to policy, pushing down rates in quarter point increments.

Also, the Fed will tend to resist large moves because they do not want to be caught wrongfooted by a surprise improvement in the global economy or a thawing of trade tensions. They surely see how the market rallies on positive trade news and will fear that excessively cutting rates now will set the stage for financial instability or economic overheating if trade tensions rapidly dissipate. To be sure though, should a major negative trade or global event like a hard Brexit occur that make the risks all too real, the Fed would respond with a large hike cut.

I think the most likely path forward for policy after next week is another rate cut in October. I don’t think the trade uncertainty will dissipate sufficiently between now and then to alleviate the Fed’s concerns, nor is there likely to be a sudden improvement in the data flow.

What about more than a total of 75bp of easing? Could it be 100bp? Or 125bp? That’s an interesting question. I currently tend toward a fairly bimodal outlook. Either 75bp is enough action to, as the Fed says, “sustain the expansion,” or the economy will slip into recession and the Fed will push short rates back to zero.At this time, I am having trouble seeing much room between those two outcomes. I remain optimistic however that the economy will follow the first path.Again, it is worth repeating that although the yield curve has inverted, the Fed would typically still resist policy easing at this point in the cycle. Indeed, I think the Fed’s early shift has already yielded some positive results. See, for example, homebuilder stocks.

Still, following the logic of the on-again, off-again advice of Williams, with a 50bp cut the Fed would maximize the chance that they sustain the expansion.I think the Fed would be better off getting some momentum behind the economy now rather than waiting until risks to the outlook actually materialize. There are far too many risks to the outlook to expect they all dissipate easily. Policy uncertainty isn’t going away and will likely increase. Market participants should take note of the increasingly erratic behavior of the White House.You know what I am talking about. And it’s not just trade policy that should be of concern; don’t forget regulatory uncertainty and festering sores in the geopolitical arena (North Korea, Iran).

Bottom Line: The Fed will cut rates 25bp next week. I don’t think everyone will be happy about it; anticipate dissents. Still, don’t focus on the dissents. I get the sense that Powell is more interested in getting policy correct than forcing policy into something that achieves consensus but is not correct. I think the Fed should pull the trigger on 50bp; they are most likely going there anyways and should just get it over with. The Fed, however, will have a hard time ignoring a data flow that they see as still generally solid. Really, it is kind of a small miracle that they pivoted toward easier policy at all.