The Federal Reserve concluded its March meeting on Wednesday with a widely expected 25 basis-point rate hike and a promise of more to come. The accompanying Summary of Economic Projections also signaled that the Fed expects to overshoot its inflation target. Within the context of the central bank’s framework, policy makers have little choice but to accept some overshooting of inflation. The alternative is a much costlier recession.

Month: March 2018

Questions for Powell

Market participants widely expect the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates at the conclusion today’s FOMC meeting. The only real debate surrounding this meeting regards the Fed’s messaging. Central bankers pivoted to a more hawkish stance in recent weeks, and this shift will be reflected in the statement and accompanying Summary of Economic Projections. But will it be modestly or very hawkish, or somewhere in-between?

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s debut post-FOMC press conference should provide guidance on this issue.With that in mind, these are the questions I am hoping he will answer the following questions either directly or indirectly:

- How does “avoiding overheating” compare to “sustaining full employment”? In his most recent Congressional testimony, Powell shifted the language regarding the Fed’s policy objective to “avoiding overheating.” Does this mean the Fed’s focus is now on restricting the pace of growth more forcefully?

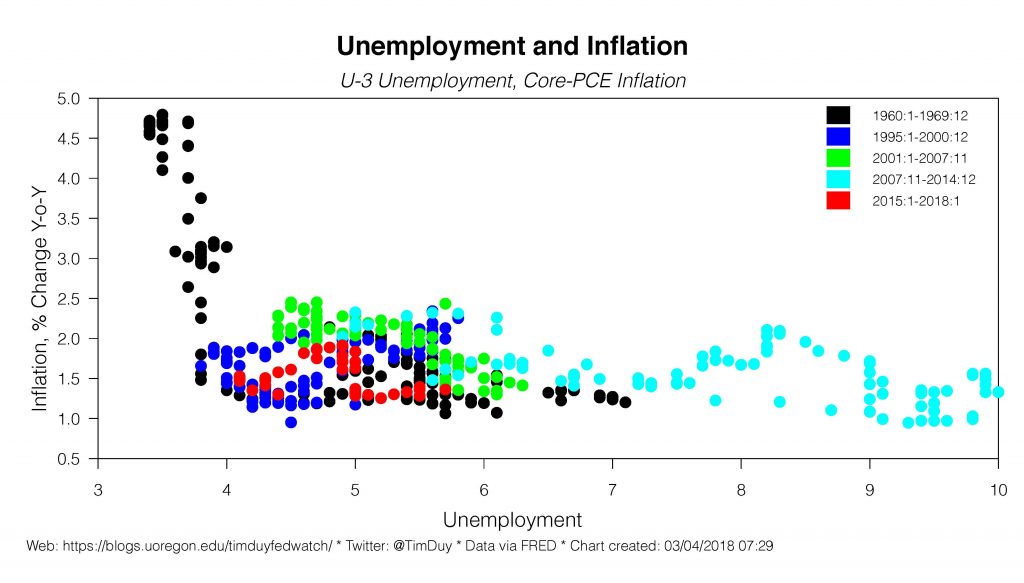

- What is the Fed’s level of confidence in the estimates of the longer-run level of unemployment? The unemployment rate is projected to sit well below the longer-run non-inflationary rate for a protracted period of time. Their willingness to tolerate this situation suggests they are not very confident in this estimate and are willing to allow the unemployment rate to fall even further than the currently forecasted low of 3.9 percent.

- Even if they are not very confident of the exact level of longer-run unemployment, is there a red line they fear to cross? In his Congressional appearance, Powell said the natural rate of unemployment may be as low as 3.5 percent. That is a level not seen for five decades and then seemed to trigger high inflation. Would they be willing to flirt with that level again? Or an even lower number?

- Is the Fed willing to invert the yield curve? The yield curve resumed flattening in recent weeks, taking the spread between 10 and 2 year securities to 55 basis points. The Fed’s forecasts indicate the Fed intends to raise rates beyond the longer-run neutral policy rates, suggesting they intend to flatten the curve further. Would central bankers deliberately invert the yield curve – or continuing hiking after an inversion – given that in the past such behavior has preceded recessions?

- How much of any increase in the rate hike projections is directly attributable to fiscal stimulus? Fiscal stimulus is one of the tailwinds supporting US growth this year and next. Given the economy was already projected to operate beyond the Fed’s estimates of full employment, the fiscal stimulus will only exacerbate the risk of overheating. How much is the Fed leaning against fiscal stimulus?

- What is the definition of “gradual” rate hikes? Suppose the Fed raises the rate projections to a full four hikes this year and three next. Is that still gradual? What if central bankers revise up rate projections again in June?

- Is the Fed looking to replace inflation worries with financial instability concerns? Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard recently said that in the last two cycles, overheating became evident not as price inflation but instead as financial instability. Does this mean that Fed intends to pivot to financial stability concerns to justify rate hikes if inflation continues to remain low? What financial stability objective is the analogue of the inflation target?

- How lopsided are the balance of risks to the outlook? Brainard described the current economic situation as the mirror image of 2015-16. The Fed sharply decelerated the actual pace of increases then relative to expectations. Should we be prepared for the opposite, a sharp acceleration?

Bottom Line: Why do the answers to these question matter? Right now, the economy is in a “sweet spot” with enough upward pressure to support ongoing improvement in labor markets yet not so much that inflation is a concern. Sustained activity in this territory will deepen and broaden the benefits of this expansion to a greater share of the population. Moreover, by moving gradually the Fed has been able to extend the life of this expansion. Indeed, the odds favor that this expansion will be record breaking in length. When the Fed turns hawkish and steps up the pace of rate increases, however, is when we need to be increasingly concerned that, like all good things, this expansion will come to an end.

Rate Hike On The Way

Market participants correctly anticipate that the Federal Reserve will hike interest rates at the conclusion of this week’s FOMC meeting. The accompanying statement and economic projections will compare hawkishly to previous iterations from past January and December, respectively. But how hawkishly? While the “dots” representing individual interest rate forecasts will rise, they may not yet rise enough to signal a fourth rate hike this year.

We are covering some well-worn ground at this point. Central bankers began sounding a more hawkish note with Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s testimony before Congress. Powell’s “headwinds to tailwinds” story was fleshed out further in a speech by Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard. A particularly salient point of that speech was Brainard’s analogy of the current situation as the “mirror image” of the situation facing the Fed in 2015-16. During that period, the Fed sharply scaled back the expected pace of rate increases. The implication then is that the Fed may sharply raise the pace of rate hikes this year.

Still, it is not evident that they in fact need to accelerate the pace of rate hikes beyond the expected three. In general, incoming data on growth, unemployment, and inflation appears broadly consistent with the Fed’s expectations for this year. Sufficiently consistent that, considering the economic tailwinds from global growth, fiscal stimulus, and easy financial conditions, those FOMC participants who viewed two rate hikes as likely will up their forecasts to three.

The doves snugging up their policy forecasts will raise the average rate hike expectation, but this by itself would be unlikely to lift the median forecast. To lift the median, central bankers already confident with the inflation forecast will need to respond to freshly announced fiscal stimulus by raising their projections as well. It is not clear to me that enough of the current three dotters raise their forecasts to bump up the median to a full four hikes this year.

I am more confident that the median rate hike expectation for 2019 will rise to a full three hikes, and that we will see the 2020 rate projections rise as well. The additional fiscal stimulus announced since the last FOMC meeting suggest above-trend growth will persist longer than anticipated. The Fed will tend to believe policy needs to be somewhat tighter to compensate.

Other things to look for:

- The longer-run policy rate. My expectation is that increases in the near- and medium-term rate projections will exceed any increase in the longer-run, or neutral, policy rate. That would suggest that central bankers anticipate that they are not chasing the long-end of the yield curve to hold policy neutral. Instead, they anticipate that they are reducing accommodation in an effort to slow the pace of activity. That would imply a flatter yield curve in our future.

- The longer-run unemployment rate. The ongoing persistence of tepid wage growth opens up the possibility the Fed might lower its estimate of the longer-run unemployment rate. That might weigh against any declines in the unemployment forecasts for this year and next that may occur if fiscal stimulus raises the growth forecasts.

- Commentary on the balance of risks. In his testimony, Powell said that the goal of policy was now to avoid overheating. That implies that the balance of risks are weighted toward inflation. Similar holds for Brainard’s comments about tailwinds to activity. Consequently, I think we should be looking for a signal in the statement communicating that the path of policy is more likely to be tighter than anticipated than looser.

- Press conferences at every meeting? There is a possibility that Powell opts for a press conference at each meeting. This would make every meeting truly “live,” compared to now when meetings without press conference are only sort of “live.” It would also open up more of a possibility that the Fed could front load some of this year’s expected hikes.

- Possible extra hawkish surprise in the dots? The Fed tends to be slow moving outside of a crisis. That one reason why we might not see enough dots move up to push the median forecast to four hikes for this year. But we could have a hawkish surprise if some participants up their forecast by 50bp instead of 25bp. That seems unlikely, but not impossible if, for example, increase confidence in the outlook was with 25bp and fiscal stimulus worth another 25bp.

Powell will of course use the press conference to emphasize (or not) any feature of the statement or projections as he deems necessary. Overall, I think he will want to continue to thread the needle between signaling the possibility of an even faster pace of rate hikes while maintaining the language of gradualism.

On another note, we should keep an eye on the recent LIBOR-OIS spread widening. It seems reasonable that no single reason accounts for the widening, but rather a combination of Fed rate hikes, the threat of more rate hikes, balance sheet reduction, dollar repatriation, and fiscal policy. As these issues become more fully priced into markets, we may see the spread narrow. Something to watch for: Perhaps one can argue that we are seeing the impact of tighter monetary policy? It would be interesting if the Fed sees it the same way.

Bottom Line: Increased confidence in the outlook and more fiscal stimulus when the economy may already be at full employment sets the stage for the Fed to boost rates and rate forecasts. But they will be wary of spooking the markets with too much hawkishness. Look for the Fed instead to describe the more hawkish policy stance as still gradual, but with the possibility that something less gradual may be near.

Inflation Still Soft

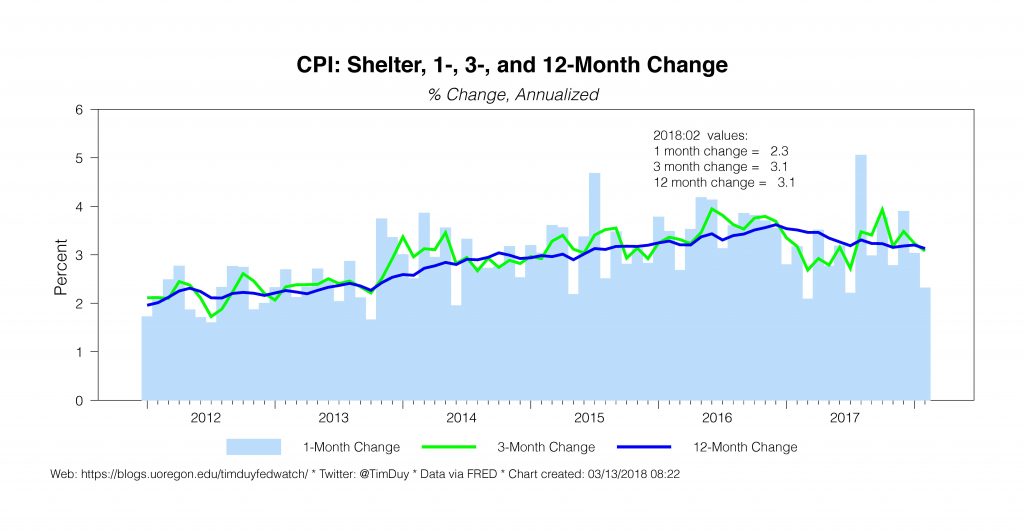

Consumer price inflation eased back from the January spike, silencing concerns that inflation would soon make a comeback. This will help keep the Fed focused on its gradual tightening path. If they want to shift gears, they will have to look elsewhere.

Core CPI decelerated in February to 0.2 percent month-over-month, compared to a 0.3 percent gain the previous month. The annualize monthly gain was 2.2 percent. Be wary of reading too much into the three-month gain of 3.1 percent as that will quickly come down if the monthly readings stay low.

It is worth considering that the stronger December and January numbers reflected some unaccounted for seasonal factors. Given the low inflation environment, the numbers of times firms change prices during the year decreases, and the timing of those changes are concentrated around the beginning of the year (a natural time to change prices). If so, then the December and January numbers were largely transitory.

Two additional points in this quick post. First, with multifamily housing starts holding strong, gradually declining shelter inflation will likely continue to weigh on overall inflation. Second, PCE inflation, the Fed’s actual inflation target, traditionally runs roughly 50bp below core. So a 2.2 percent core CPI inflation implies something like 1.8 percent core PCE inflation. That is still weak relative to the Fed’s two percent inflation target.

Bottom Line: Inflation numbers help confirm the Fed’s current forecast, but don’t signal any overshooting of their target yet. The Fed hence can’t yet place an accelerated pace of rate hikes on the back of actual inflation. Changes in the rate forecast instead remain attributable to risk management considerations as tailwinds threatens to push the economy into overheating that would reveal itself in either excessive inflation or financial instability.

Jobs Report Gives Fed Cover To Retain Gradual Rate Path

The jobs report gives the Fed cover to retain a gradual rate path. To be sure, the rapid pace of job growth will leave them nervous about an unsustainable pace of growth. But the flat unemployment rate remains consistent with their forecasts. In addition, low wage growth indicates the economy has not pushed past full employment. If inflation remains constrained, the Fed would be pretty much on target for this year. That suggests the three-hike scenario should remain in play. But increased confidence in the outlook and risk management concerns will push up enough “dots” in the next Summary of Economic projections toward four hikes for this year.

Continued here as a newsletter…

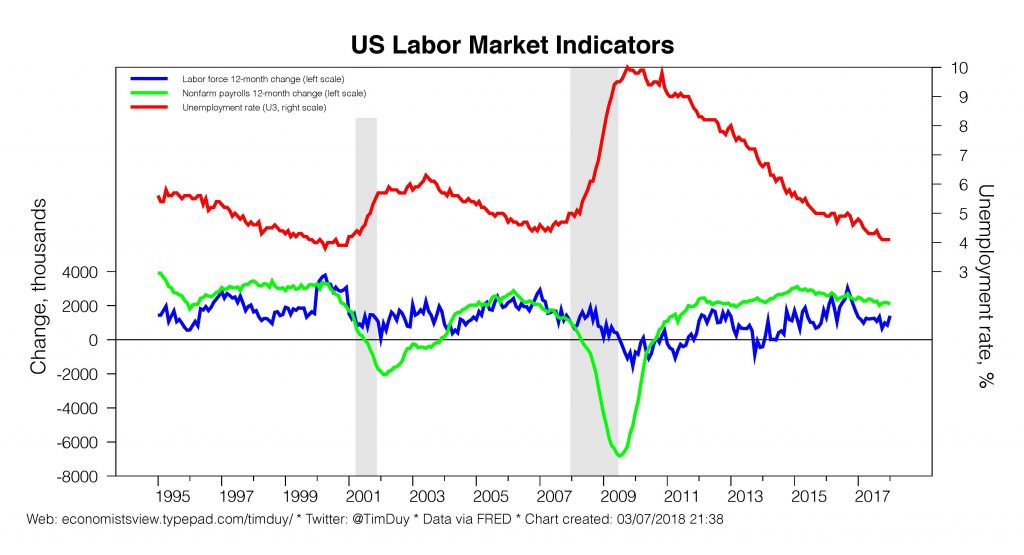

Nonfarm payrolls grew by in February while previous months were revised upwardly. The three-month moving average is 242k while the twelve-month average is 190k. These are solid numbers for an economy this deep into an economic expansion, the result of the acceleration of activity over the past year. Job gains continue to exceed the rate at which central bankers believe will eventually be the rate of labor force growth when secular factors dominate cyclical behavior. That time, however, continues to be postponed. The unemployment rate held steady again at 4.1 percent; my concerns that unemployment would soon shift downward continue to be just concerns and not reality. Instead, growth in prime-age labor force participation continues to support overall labor force participation. If this trend continues, then we would expect that the unemployment rate will generally track in line with the Fed’s forecast despite growth well in excess of long-run potential growth.

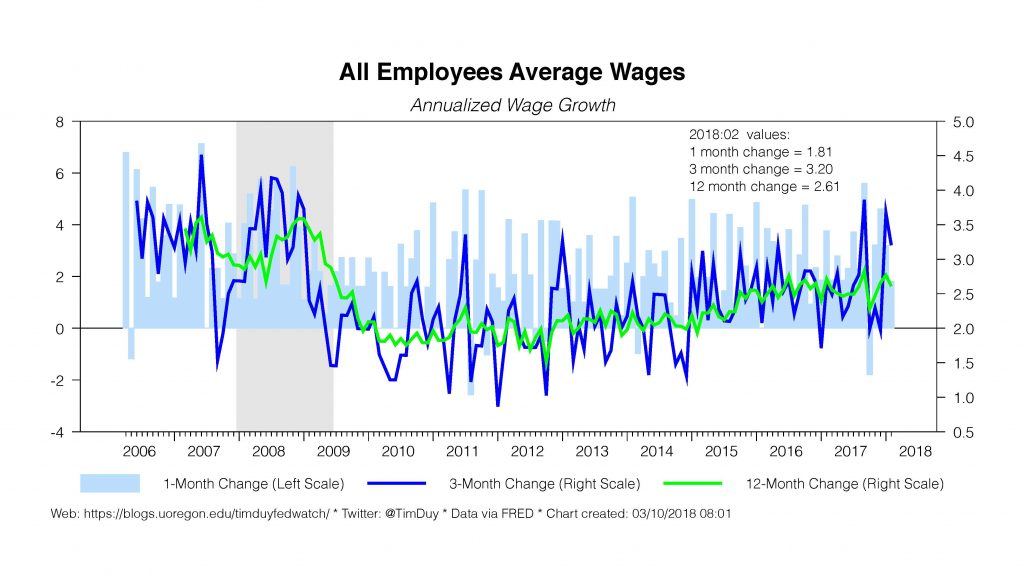

Job gains continue to exceed the rate at which central bankers believe will eventually be the rate of labor force growth when secular factors dominate cyclical behavior. That time, however, continues to be postponed. The unemployment rate held steady again at 4.1 percent; my concerns that unemployment would soon shift downward continue to be just concerns and not reality. Instead, growth in prime-age labor force participation continues to support overall labor force participation. If this trend continues, then we would expect that the unemployment rate will generally track in line with the Fed’s forecast despite growth well in excess of long-run potential growth. More generally, the recovery of prime-age participation (alone with still relatively high levels of other underemployment indicators) suggests that the economy can sustain further cyclical gains without overheating. In other words, the economy might be quite a bit farther from full-employment than indicated by Federal Reserve estimates of the longer-run unemployment rate. Weak wage growth also argues against the full-employment hypothesis. Wage growth decelerated in February, quelling hopes for a more sustained acceleration.

More generally, the recovery of prime-age participation (alone with still relatively high levels of other underemployment indicators) suggests that the economy can sustain further cyclical gains without overheating. In other words, the economy might be quite a bit farther from full-employment than indicated by Federal Reserve estimates of the longer-run unemployment rate. Weak wage growth also argues against the full-employment hypothesis. Wage growth decelerated in February, quelling hopes for a more sustained acceleration. Although wage growth decelerated, hours worked jumped, which will help support overall compensation and provide a base for continued consumer spending. In addition, a jump in temporary help payrolls indicates this labor market isn’t about to hit a wall anytime soon.

Although wage growth decelerated, hours worked jumped, which will help support overall compensation and provide a base for continued consumer spending. In addition, a jump in temporary help payrolls indicates this labor market isn’t about to hit a wall anytime soon.

The Federal Reserve should be comforted by this report as it argues in favor of the gradual rate hike approach. If labor supply is responding positively to a higher pace of economic activity, the Fed should worry less about overheating despite the solid pace of wage growth. Moreover, continued tepid wage growth should weigh down on their estimates of full-employment. This report simply doesn’t indicate that the natural rate of unemployment is as high as the Fed believes.

This report should, like recent inflation numbers, reassure the Fed of its 2018 forecasts. That will induce those policymakers most skeptical of the inflation outlook to revise their below-consensus rate estimates higher, bumping up the lower dots. In addition, with their forecasts looking likely to hold, those at or above consensus would be expected to hold their estimates steady. There will, however, be upward pressure to rate even those dots.

Risk management concerns will drive the upward pressure on rate projections. The Fed tends to believe the economy has more likely than not achieved or surpassed full employment (regardless of that pesky wage, inflation, and labor force participation data). They also see headwinds changing to tailwinds that threaten to sustain stronger growth for longer than expected that pushes the economy deeper into a danger zone in 2019 and 2020. Finally, the last two cycles left central bankers wary that a hot-economy will reveal itself in financial instability rather than inflation. All together that suggests they will want to project a slightly tighter policy and be prepared to move more aggressively if needed. This will reveal itself in the next Summary of Economic Projections.

Bottom Line: Recent employment reports combine to tell a story of an economy that can sustain a faster pace of growth without pushing past capacity boundaries. That argues for leaving the Fed’s expected policy rate path intact. But Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s testimony pointed to “avoiding overheating” as a policy objective while Federal Reserve Govenror Lael Brainard discussed at length the shift of economic forces from headwinds to tailwinds. She drew a comparison to 2015-16, when the Fed sharply reduced the pace of hikes relative to the projected rate path. Together, these discussions suggest the Fed sees a shifting balance of risks to the outlook. They will try to manage the risks accordingly, bumping up estimates of future rates while leaving open the option to switch to a more sharply more aggressive path if needed.

Employment Report Coming Up

Some of the fog around monetary policy lifted in recent days. Central bankers, increasingly confident on the inflation outlook, look to be firming up their rate forecasts. In practice, this means that those who were wary that inflation would rebound as expected will likely raise their “dots” up a notch toward the current median expectation of three dots. See, for example, Atlanta Federal President Raphael Bostic. It is not clear yet if those who were already confident of the inflation forecast will raise their policy expectations. Hence, the 2018 dots might climb but the median remains at three rate hikes. In addition, given current momentum in the US economy, fueled by tail winds from just about everyone, there remains room to pull up the 2019 and 2020 dots.

A March bump in rate forecasts, however, overlooks a bigger issue. Uncertainty over the rate forecast is growing – but not symmetrically. The risks are shifting toward a greater pace of rate hikes. The existing forecast already contained plenty of upside risk for rates. But the addition of fiscal stimulus threatens to push the unemployment rate into a region in which the Fed has little experience. The situation, according to Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard, is essentially a mirror image of 2015-16. Then, the Fed sharply slowed the pace of rate hikes relative to expectations. The mirror image risk is that central bankers sharply raise the pace.

Nothing of course is written in stone at this point. We don’t yet know when or if the economy would overheat. But the Fed may have to react quickly if it does.

With that in mind, central bankers will carefully scour the employment report for signs of potential overheating. In a broad sense, we would see that in three places – job growth, unemployment rate, and wage growth. The consensus forecast for nonfarm payrolls is for a gain of 205k in a range of 152k-230k. My estimate is 208k, leaving me in line with the consensus.

The Fed estimates job growth of only roughly 100k is necessary to hold the unemployment rate steady. Hence, continued job growth well in excess of that number will be looked upon warily. In the near term, gains in labor force participation may hold the unemployment rate steady. Over the medium term, however, that pace of growth will eventually place downward pressure on unemployment and increase the degree by which the economy overshoots full employment.

Indeed, job growth already exceeds labor force growth, but the unemployment rate has remained steady in recent months. The consensus expectation is for unemployment to dip slightly to 4 percent. I still remained concerned that unemployment will lurch lower in a fairly short amount of time – such a development would clearly rattle the Fed. Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics is forecasting a 2.5 percent unemployment rate by next summer under the Fed’s current rate path.

Then there is wage growth, which perked up in December and January. Wall Street expects wages to be up 2.9 percent compared to last year, the same as in January. The acceleration in wage growth in recent months gives fresh supportive evidence to the hypothesis that the economy is near full employment; an acceleration would add to that evidence.

It is important remember that an acceleration in wages does not necessarily imply an acceleration in inflation. Wage growth could be absorbed by profit margins instead. In theory, that means the Fed would not should not respond reflexively to a wage acceleration – they target inflation, not wages. In practice, however, Brainard indicated that in the last two cycles, the imbalance of an overheated economy became reflected in financial instability rather than inflation:

We also seek to sustain full employment, and we will want to be attentive to imbalances that could jeopardize this goal. If the unemployment rate continues to decline on the current trajectory, it could fall to levels that have been rarely seen over the past five decades. Historically, such episodes have tended to see elevated risks of imbalances, whether in the form of high inflation in earlier decades or of financial imbalances in recent decades.

This suggests that the Fed might be incline to tamp down growth even in the absence of inflationary pressures.

I am not sure I am a big fan of Brainard’s interpretation. I would like to better understand the causality. She seems to imply that low unemployment rates caused financial instability. I tend to think of it the other way around – that the financial instability of asset bubbles drove clear surges of investment activity. The subsequent activity drove down unemployment. In this cycle, activity is much more broad-based with no single sector outperforming on the back of an asset bubble. I am not sure they should take the focus off the price mandate for a less defined financial stability mandate.

Bottom Line: With the economy nearing full employment, or having already overshot full employment, the Fed will find it hard to rest easy until job growth eases back to something they believe to be a more sustainable pace. But they are less likely to shift dramatically away from a gradual pace of rate hikes as long as unemployment hovers close to four percent and wage growth doesn’t leap higher. Of course, this would become less relevant if inflation made a stronger appearance. In that case, it would be more evident they pushed past critical boundaries for activity and need to respond more forcefully.

Brainard Speech Has Something For Everyone

Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard gave her policy guidance as Fed officials continue to set the stage for this month’s FOMC meeting. There is something for everyone in this speech, but it concludes with a strong warning that evolving economic conditions might force the Fed into a faster pace of rate hikes.

The speech is somewhat fascinating in the degree of care taken in delivering her message. This I suspect reflects fears that market participants will react poorly to any hint that the Fed may accelerate the pace of rate hikes. Brainard begins:

Many of the forces that acted as headwinds to U.S. growth and weighed on policy in previous years are generating tailwinds currently. Today many economies around the world are experiencing synchronized growth, in contrast to the 2015-16 period when important foreign economies experienced adverse shocks and anemic demand.

She is comparing the current period to 2015-16. Keep that in mind – it becomes important for the conclusion. In comparison to then, the global economy is stronger, the dollar is falling, oil prices are rising, US business investment is on the rebound, and financial conditions are supportive of growth. In addition:

The most notable tailwind is the shift in America’s fiscal policy stance from restraint to substantial stimulus in an economy close to full employment. In the earlier period, the economy had just weathered a challenging adjustment to a sharp withdrawal of fiscal support. Today, from a position near full employment, the economy is poised to absorb $1-1/2 trillion in personal and corporate tax cuts and a $300 billion increase in federal spending. Estimates suggest December’s tax legislation could boost the growth rate of real gross domestic product (GDP) as much as 1/2 percentage point this year and next. On top of that, the recently agreed-to budget deal is likely to raise federal spending by around 0.4 percent of GDP in each of the next two years.

There are two important points here. First, she describes the economy at near full employment. Second, she estimates the impact of new fiscal spending at 0.4 percentage points of GDP. Think about the combination for a second. The Fed forecasts from December expect 2.5 percent growth in 2018, relative to a 1.8 percent potential growth rate. If the fiscal spending since that forecast feeds into the GDP forecast one for one, that amounts to 2.9 percent growth in 2018. Relative to 1.8 percent potential. For an economy near full employment.

It is easy to see how, with that forecast, unemployment blows straight through Fed’s current forecast of 3.9 percent for the end of the year (actually, it is easy to see how that happens even without the additional fiscal spending). Keep a close eye on the forecasts in the next Summary of Economic projections. Watch for inconsistencies. How much is the growth forecast revised upward? How much is unemployment revised downward? That’s where you will find the risks to the rate forecast.

After describing the tailwinds, the dovish side of Brainard makes an appearance:

The persistence of subdued inflation, despite an unemployment rate that has moved below most estimates of its natural rate, suggests some risk that underlying inflation may have softened…it is important for monetary policy to ensure that underlying inflation is re-anchored firmly at 2 percent.

Brainard still has concerns that inflation expectations have dipped, and wants to see those expectations pulled back up to 2 percent. That suggests no rush to hike rates. And the other half of the dual mandate:

At the same time, it is important for monetary policy to sustain full employment.

This is interesting. Remember that in Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s testimony last week, the story on the labor market was “avoiding overheating.” Brainard pulls that back to “sustaining full employment.” Is Brainard trying to un-ring that bell? I am hoping someone asks Powell about the overheating line in the upcoming press conference.

How near is “near” full employment? Who knows? Brainard:

It is difficult to know with precision how much slack remains in the labor market. If the unemployment rate were to continue to fall in the coming year at the same pace as in the past couple of years, it would reach levels not seen since the late 1960s.

I have heard that comparison to the late 1960’s somewhere before. Still, Brainard is at least modestly optimistic that there remains some slack in the labor market. With inflation expectations still a little soft and some lingering slack in the labor market, Brainard blesses the Fed’s current anticipated rate path:

Although last year we faced a disconnect between the continued strengthening in the labor market and the step-down in inflation, mounting tailwinds at a time of full employment and above-trend growth tip the balance of considerations in my view. With greater confidence in achieving the inflation target, continued gradual increases in the federal funds rate are likely to be appropriate.

That sounds like a move from two dots to three for 2018. She also, appropriately in my view, emphasizes that inflation overshoots were perfectly acceptable:

Of course, it is conceivable we could see a mild, temporary overshoot of the inflation target over the medium term. If such a mild, temporary overshoot were to occur, it would likely be consistent with the symmetry of the FOMC’s target and could help nudge underlying inflation back to our target.

Then come the warnings:

We also seek to sustain full employment, and we will want to be attentive to imbalances that could jeopardize this goal. If the unemployment rate continues to decline on the current trajectory, it could fall to levels that have been rarely seen over the past five decades. Historically, such episodes have tended to see elevated risks of imbalances, whether in the form of high inflation in earlier decades or of financial imbalances in recent decades.

Follow that for a second. Brainard is saying the imbalance might not be inflation, but financial. For those of you worried that the Fed isn’t paying enough attention to asset prices, that line is for you. She is clearly ready to fight the last war if need be.

Brainard references the flat Phillips curve and low wage gains, but comes back to this point:

However, we do not have extensive experience with an economy at very low unemployment rates and cannot be sure how it might evolve. In particular, we will want to remain attentive to the risk of financial imbalances. While asset valuations appear to be elevated, overall risks to the financial system remain moderate because household borrowing is moderate, risks associated with liquidity and maturity transformation have declined, and, importantly, the banking system appears to be well capitalized. History suggests, however, that a booming economy can lead to a relaxation in lending standards, and the attendant excessive borrowing can complicate the task of monetary policy. We will need to be vigilant.

Back to the financial imbalances. Another signal that while she might not be worried about inflation, she is worried about the sowing the seeds of financial crisis.

The punchline is the conclusion:

In many respects, the macro environment today is the mirror image of the environment we confronted a couple of years ago. In the earlier period, strong headwinds sapped the momentum of the recovery and weighed down the path of policy. Today, with headwinds shifting to tailwinds, the reverse could hold true.

Back to the 2015-16 comparison. Let’s think about that for a second. In 2015, Brainard sounded the alarm on the Fed’s expected rate path. She was ultimately proven correct; the Fed’s expected four hikes in 2016 became just one. That’s a sharp deceleration relative to the expected path. Today’s economic environment is a “mirror image” of then. That opens the door to a sharp acceleration. That’s the warning – the balance of risks has shifted. If she is as prescient as she was in 2015, you know what’s coming.

Bottom Line: Lots to chew on here. But ultimately, it sounds as if Brainard is throwing off her more dovish concerns of last year and is ready to come into the consensus. But more ominous is her warning: The economy is near full employment with substantial tailwinds that could quickly push the Fed into uncharted territory. Unspoken directly of course is that the situation might reverse if the chaos in the White House derails the US economy.

Questions

The written testimony accompanying Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s visits to Capitol Hill last week left me with more questions than answers. It seems evident that central bankers expect they will need to boost their estimates of appropriate rate hikes either in March of June. It also appears that they would like to make this shift while remaining within the context of the existing policy language of gradualism.

That is a tricky needle to thread, and I understand the motivation. Policy makers simply do not want to spark a sell-off in Treasuries. But the past week has left me wondering if the Fed’s affection for gradualism has left us too complacent about the possibility of a rapid shift away from gradualism. I have lots of questions:

Continued here as a newsletter…

What is the current status of the business cycle? The Fed’s description of its policy objectives made a little noticed transition in testimony over the past six months from “achieve” full employment to “sustain” full employment to “avoiding overheating.” I interpret that as an evolution from a mid-stage to a mature-stage to a late-stage in the cycle.

The late-stage arguably poses the most challenging for policy makers. In the late-stage of the cycle, the pace of activity needs to ease lest the economy overheat and inflationary pressures emerge. Central bankers will thus be under pressure to tighten policy more quickly but fear too much tightening will kill the expansion. In my mind, this stage requires a nimble policy stance, maybe raising rates more quickly with the expectation they may have to be cut more quickly. Such a policy stance, however, would induce uncertainty into financial markets, which the Fed tries to avoid. In an attempt to reduce that uncertainty, they have tethered themselves to gradualism.

What is the definition of “gradual”? New York Federal Reserve President William Dudley placed some boundaries on that concept last week, seeming to say that four hikes would still be gradual while the eight annual hikes of past cycles were the alternative to gradual.

There is a lot of space between four and eight hikes. Does Dudley believe seven hikes this year is gradual? I think that market participants would disagree and, for example, see five hikes as the alternative to gradual. Moreover, there is a case that “gradual” should be based on the expected endpoint, the neutral rate. If so, then with the neutral rate lower now than in past cycles, the Fed may be tightening policy at roughly the same pace as those cycles even though the actual hikes occur more slowly. And by that logic, maybe a shift from three to four rate hikes is a meaningful acceleration because the Fed is closing the gap to neutral more quickly.

Does the Fed expect to increase in the pace of rate hikes to reduce financial accommodation? On first glance, this may seem a silly question. Of course! Why else would they raise rates? Maybe though they just intend to chase the neutral rate higher. In other words, they sense the neutral rate is drifting higher than anticipated, and they need to adjust policy accordingly to maintain constant financial accommodation.

Alternatively, they may believe the real rate is holding steady, but economic tailwinds require additional rate hikes to reduce accommodation. There is also the possibility that both the natural rate is drifting up and economic tailwinds necessitate that the Fed reduces financial accommodation. This requires then an even greater rise in the expected rate path.

Which is it? Is raising the expected policy path to compensate for both a need to tighten and a higher neutral rate is a gradual path? The answer guides us on the type of interest rate environment to expect – a steady to steepening curve versus flattening. From my perspective, I don’t see how you can respond to prospects of overheating with just chasing the long end of the yield curve. It has to be something more.

What’s up with the Fed’s forecasts? Currently, the unemployment rate is 4.1 percent. The decline in 2017 was 0.7 percentage points. The Fed expects growth this year equivalent to last’s but only a 0.2 percentage point decline in the unemployment rate. That just doesn’t add up. And that was before the additional fiscal spending was added to the outlook. But the Fed would have a hard time forecasting another 0.7 percentage point drop this year in the unemployment rate without changing the interest rate and inflation forecasts accordingly. That or a very sharp and arguably questionable reduction in the estimate of the longer-run unemployment rate.

Yes, growth in the labor force or productivity may come to the rescue. But I think it more likely that the unemployment rate makes a sharp drop downward. Job growth has remained well above labor force growth in recent months; it is already somewhat surprising then that unemployment has held steady over that time.

Hence, I see a high risk that the unemployment rate drops to a very uncomfortable level for the Fed when they are already focused on avoiding overheating. At that point, I am guessing they will evolve again from “avoiding” to “responding to” overheating.

What is the realistically acceptable lower bound for unemployment? When do officials become very uncomfortable? The median unemployment rate forecast for the end of this year and next is 3.9 percent. The low of the central tendency of projections is 3.6 percent for 2019. Powell said the longer-run rate of unemployment may be as low as 3.5 percent.

The problem with all of these forecast is that all intents and purposes, a sustained unemployment rate much below 4 percent is basically uncharted territory. The last time the economy sustained such a low level was the late-1960s.

The late-1960s analogy is very interesting. Much has been written of the flat Phillips curve; for more than 20 years inflation concerns have proven overblown. Funny thing though – the Phillips curve was flat for much of the 1960’s as well. Right up until the end of the decade, when inflation quickly emerged – during a sustained period of below 4 percent unemployment. Fiscal stimulus came into play at that time as well. From the 1968 Economic Report of the President:

Nevertheless, the fuller use of resources posed new problems of diagnosis and policy application. Previously, the risks had been almost entirely on the side of insufficient demand; and the primary task of policy had been to provide stimulus. As the unemployment rate fell toward 4 percent, the economy entered territory that had been uninhabited for nearly a decade. There were now risks on both sides—not only of inadequate but of excessive stimulus.

This warning was probably too late by 1968. With such history, and given the likely direction of risk to the forecast, I think it completely reasonable that central bankers would shift the goalposts to avoiding overheating. But that requires them to own a stronger view on the reasonable boundary for unemployment.

Bottom Line: If I step back and take a dispassionate view of the situation, I see where Powell & Co. would need to shift gears in the near future. Somewhere around 4 percent unemployment seems to be a sweet spot for the economy. I would want to stay here as long as possible; that seems safest if one wants to avoid overheating yet still keep sustained pressure on the job market. We might be able to push lower, but the territory is uncharted. Here be dragons? But the Fed’s forecast was at risk of blowing past this level even before the extent of the fiscal stimulus became evident. In other words, the gradual pace of tightening may have been too gradual. That is not a criticism as much as an observation; I have long argued that the Fed should push boundaries in this expansion. That said, this was with the expectation that the Fed would quickly shift gears and abandon gradualism when needed. It might take some nimbleness on the part of the Fed to hold the economy steady. Hence, the Fed’s communication emphasis on gradualism – to the point that seemingly anything less than eight hikes a year is gradual – may be lulling market participants into complacency when no such complacency is warranted. The situation may change quickly.

Fed Changing Its Tune

Yesterday I called attention to this line from Federal Reserve Chairman Powell’s testimony:

In gauging the appropriate path for monetary policy over the next few years, the FOMC will continue to strike a balance between avoiding an overheated economy and bringing PCE price inflation to 2 percent on a sustained basis.

I interpreted this as a shift in the Fed’s focus. The risks are shifting, hence the new concern about an overheated economy. In contrast, previous iterations of this policy guidance referred to “achieving” and then “sustaining” full employment. Central bankers must view the economy as in a danger zone for inflationary pressures.

The next line of the testimony reads:

While many factors shape the economic outlook, some of the headwinds the U.S. economy faced in previous years have turned into tailwinds: In particular, fiscal policy has become more stimulative and foreign demand for U.S. exports is on a firmer trajectory.

The Fed’s forecast was already only tenuously supportive of three rate hikes. The extra stimulus hence throws the economy into the red zone. If we had any doubt that this policy shift was underway, Julia Coronado of Macropolicy Perspectives catches the topic of Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard’s speech next week:

“Navigating Monetary Policy as Headwinds Shift to Tailwinds.”

Yeah, that’s not a coincidence. That’s kind of hitting us over the heads to prepare ourselves for changes in the forecasts and the statement with the next FOMC meeting. First thought is that we will see the “overheating” language appear in the statement, which is to be interpreted as a warning that while they intended to maintain gradual rate hikes, it is more likely that incoming data will trigger an increase rather than decrease the pace of hikes.

Yes, inflation is below the 2 percent target, so on this surface this change in tone seems ludicrous. But the median policy maker forecast in the most recent Summary of Economic Projections is also quite frankly ludicrous. Those forecasts indicate growth well above potential growth in 2018 yet only a small decline in the unemployment rate. And stabilizing unemployment in 2019 with yet another year of growth above potential. And the inflation rate only returns to 2 percent when the temporary factors lift, but by the Fed’s Phillips curve approach the beyond-full employment economy should be much more inflationary when those factors lift, well above the 2 percent target. It all screams for a faster than 3 rate hike pace in 2018, but that was the median policy maker forecast.

I tend to think, and have thought for a long time, that the forecast was essentially reverse engineered as much as possible to keep the rate forecast at three hikes in 2018. Now, with the additional tailwinds sustaining momentum in the economy, they can no longer maintain this façade. Hence the change to the threat of “overheating.”

Bottom Line: I don’t think this is just about three or four hikes. It strikes me as something bigger, a more fundamental change in the policy objective. I understand if you want to resist such an interpretation. We, myself included, all have a lot of ink spilled on gradualism, so there is a natural resistance to changing the story. But as I said Monday, it felt like policy expectations had been set adrift during the transition and I was looking for Powell to re-anchor those expectations. That’s what it looks like he is doing. But he is raising as many questions as he is answering. For instance, I think we need to give some extra weight to the view that 2 percent inflation is a ceiling, not a symmetric target. And now we will be talking about monetary offset. Should get interesting.