Some of the fog around monetary policy lifted in recent days. Central bankers, increasingly confident on the inflation outlook, look to be firming up their rate forecasts. In practice, this means that those who were wary that inflation would rebound as expected will likely raise their “dots” up a notch toward the current median expectation of three dots. See, for example, Atlanta Federal President Raphael Bostic. It is not clear yet if those who were already confident of the inflation forecast will raise their policy expectations. Hence, the 2018 dots might climb but the median remains at three rate hikes. In addition, given current momentum in the US economy, fueled by tail winds from just about everyone, there remains room to pull up the 2019 and 2020 dots.

A March bump in rate forecasts, however, overlooks a bigger issue. Uncertainty over the rate forecast is growing – but not symmetrically. The risks are shifting toward a greater pace of rate hikes. The existing forecast already contained plenty of upside risk for rates. But the addition of fiscal stimulus threatens to push the unemployment rate into a region in which the Fed has little experience. The situation, according to Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard, is essentially a mirror image of 2015-16. Then, the Fed sharply slowed the pace of rate hikes relative to expectations. The mirror image risk is that central bankers sharply raise the pace.

Nothing of course is written in stone at this point. We don’t yet know when or if the economy would overheat. But the Fed may have to react quickly if it does.

With that in mind, central bankers will carefully scour the employment report for signs of potential overheating. In a broad sense, we would see that in three places – job growth, unemployment rate, and wage growth. The consensus forecast for nonfarm payrolls is for a gain of 205k in a range of 152k-230k. My estimate is 208k, leaving me in line with the consensus.

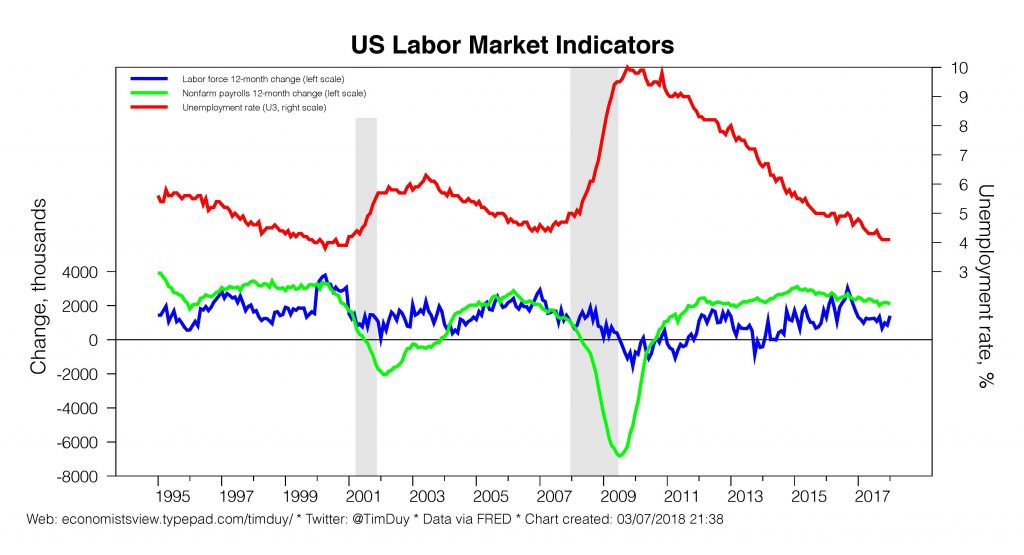

The Fed estimates job growth of only roughly 100k is necessary to hold the unemployment rate steady. Hence, continued job growth well in excess of that number will be looked upon warily. In the near term, gains in labor force participation may hold the unemployment rate steady. Over the medium term, however, that pace of growth will eventually place downward pressure on unemployment and increase the degree by which the economy overshoots full employment.

Indeed, job growth already exceeds labor force growth, but the unemployment rate has remained steady in recent months. The consensus expectation is for unemployment to dip slightly to 4 percent. I still remained concerned that unemployment will lurch lower in a fairly short amount of time – such a development would clearly rattle the Fed. Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics is forecasting a 2.5 percent unemployment rate by next summer under the Fed’s current rate path.

Then there is wage growth, which perked up in December and January. Wall Street expects wages to be up 2.9 percent compared to last year, the same as in January. The acceleration in wage growth in recent months gives fresh supportive evidence to the hypothesis that the economy is near full employment; an acceleration would add to that evidence.

It is important remember that an acceleration in wages does not necessarily imply an acceleration in inflation. Wage growth could be absorbed by profit margins instead. In theory, that means the Fed would not should not respond reflexively to a wage acceleration – they target inflation, not wages. In practice, however, Brainard indicated that in the last two cycles, the imbalance of an overheated economy became reflected in financial instability rather than inflation:

We also seek to sustain full employment, and we will want to be attentive to imbalances that could jeopardize this goal. If the unemployment rate continues to decline on the current trajectory, it could fall to levels that have been rarely seen over the past five decades. Historically, such episodes have tended to see elevated risks of imbalances, whether in the form of high inflation in earlier decades or of financial imbalances in recent decades.

This suggests that the Fed might be incline to tamp down growth even in the absence of inflationary pressures.

I am not sure I am a big fan of Brainard’s interpretation. I would like to better understand the causality. She seems to imply that low unemployment rates caused financial instability. I tend to think of it the other way around – that the financial instability of asset bubbles drove clear surges of investment activity. The subsequent activity drove down unemployment. In this cycle, activity is much more broad-based with no single sector outperforming on the back of an asset bubble. I am not sure they should take the focus off the price mandate for a less defined financial stability mandate.

Bottom Line: With the economy nearing full employment, or having already overshot full employment, the Fed will find it hard to rest easy until job growth eases back to something they believe to be a more sustainable pace. But they are less likely to shift dramatically away from a gradual pace of rate hikes as long as unemployment hovers close to four percent and wage growth doesn’t leap higher. Of course, this would become less relevant if inflation made a stronger appearance. In that case, it would be more evident they pushed past critical boundaries for activity and need to respond more forcefully.