If You Don’t Have Any Time This Morning

The tricky part is weighing the negative of rising Covid-19 cases against likely positive influences on the

Click for newsletter!

economy. We might not get the rapid recovery we were hoping for months ago, but a recovery nonetheless.

Key Data

The ISM non-manufacturing numbers bounced back in June. I wouldn’t want to read too much into this yet; it simply should be the case that activity picked up across the economy as the first round of shutdowns ended. This is a diffusion index; improving business conditions from a very low level can be easy to accomplish in this circumstance but doesn’t necessarily signal the momentum needed to support rapid recovery. More importantly, the employment component remains under 50, indicating weak labor demand. Business might be up, but not enough to promote much needed job growth. That said, the numbers are all in the right direction.

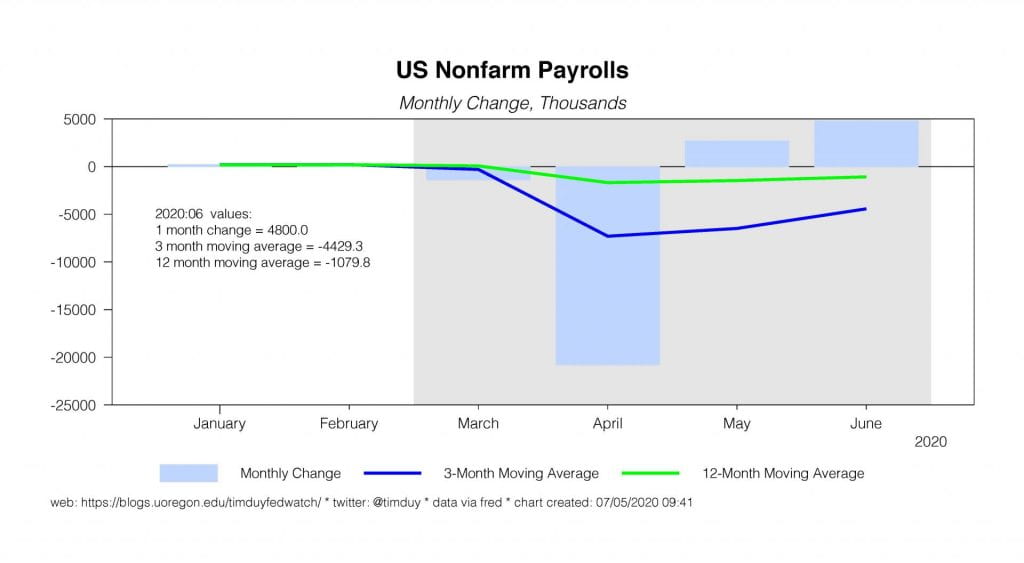

Hiring spiked in the JOLTs report for May. This isn’t exactly news as the employment report revealed a surrise jump that month as firms rehired workers separated in the early stages of the pandemic. Attention is better placed on the level of job openings. Though still much higher than the lows of the last recession, the declines indicate caution on the part of firms. Also, the level of quits might be the most telling indicator here on the state of the labor market. Employees are wisely choosing not to leave their jobs, likely fearing it will be difficult to find another.

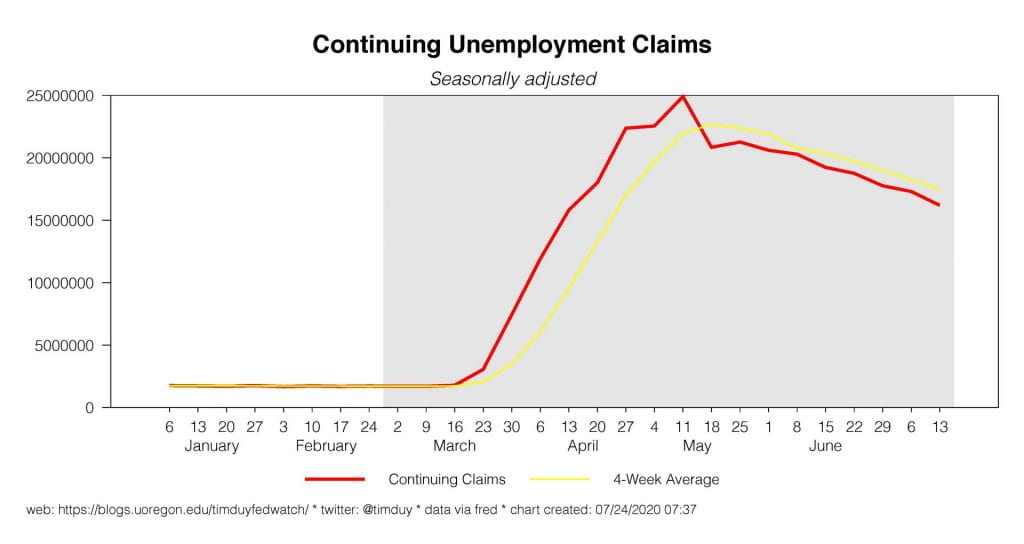

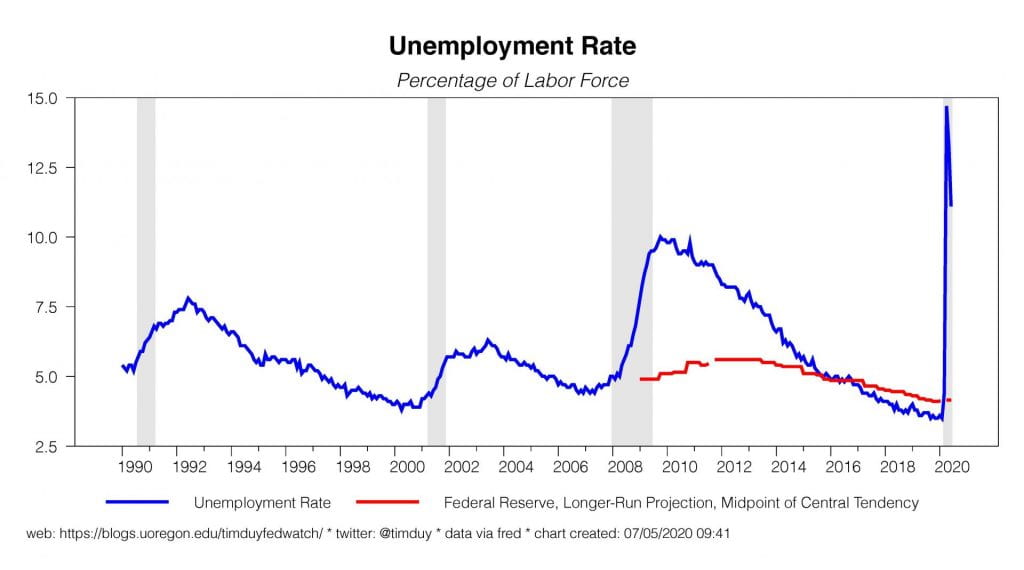

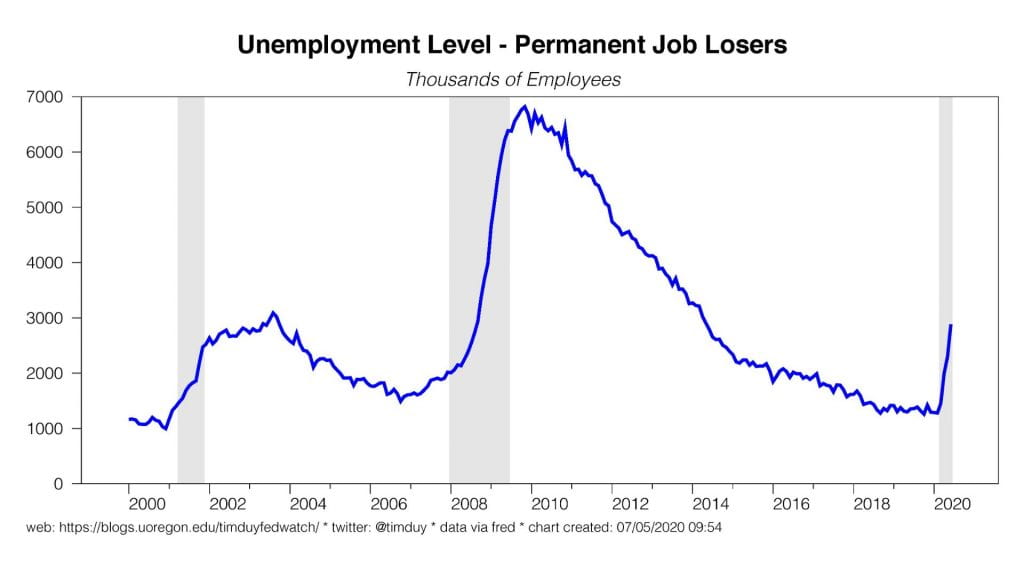

Initial unemployment claims and continuing claims remain stubbornly high. The second and third order impacts of the initial shutdown continue to force additional layoffs at a rate that exceeds the worst of the last recession. The need for ongoing enhanced unemployment benefits seems pretty clear here. It’s hard to throw people into a labor market where jobs continue to dry up, particularly if very sector specific weakness remains that prevents people from returning to their previous positions.

Fedspeak

In a Financial Times interview, Atlanta Federal Reserve President Raphael Bostic worries that the surge in Covid-19 cases will weigh on the recovery:

“There are a couple of things that we are seeing and some of them are troubling and might suggest that the trajectory of this recovery is going to be a bit bumpier than it might otherwise,” Mr Bostic said. “And so we’re watching this very closely, trying to understand exactly what’s happening.”

He correctly noted that more fiscal stimulus is needed. The original packages did not anticipate the crisis dragging past the summer as it most obviously will. Bostic is apparently cool on enhanced forward guidance:

“I think a lot of it depends on where we are. I do think that talking about the benchmarks that we’re looking at is an important thing,” he said.

“But I do worry that circumstances are going to be very different in the future than they are now and so I want to be careful about being too presumptuous about where we’re going to be. All this uncertainty is definitely in my mind”.

I am not entirely sure what he means, but it sounds like he is worried about committing the Fed to any particular policy path given the uncertainty. This quote sounds a bit wishy-washy to me. I don’t think the point of enhanced forward guidance is to presume where you are going to be. It is that you don’t know where you are going to be but you know where you want to go.

Dallas Federal Reserve President Robert Kaplan wants to strike at the heart of the problem. Via Reuters:

“How the virus proceeds, and what the incidence is, is going to be directly related to how fast we grow,” Kaplan told Fox Business Network in an interview. “While monetary and fiscal policy have a key role to play, the primary economic policy from here is broad mask wearing and good execution of these health care protocols; if we do that well, we’ll grow faster.”

It’s good to have the Federal Reserve authority from Texas reinforcing this message. Kaplan’s correct; monetary and fiscal policy will only take you so far. What the economy real needs is a public health solution to the virus.

San Francisco Federal Reserve President Mary Daly worries that unemployment will remain unacceptably high. Via MarketWatch:

“We don’t know how long it will fully take to put the virus behind us,” she said in a virtual chat held by the National Association of Business Economists. “I am assuming [unemployment] will level off at someplace we don’t want to be.”

What does this means for Fed policy? Richmond Federal Reserve President Thomas Barkin speaks the truth:

Asked if the Fed will have to do even more to help the economy, Barkin said: “Unemployment is 11%, so yes.”

Right now, any plausible scenario includes the Fed under continued pressure to do more.

Daly added that she is closely watching the possibility of nonperforming loans in the banking sector. That topic was also taken up by Federal Reserve Governor Randal Quarles. He sounded optimistic about the stability of the banking system:

Less than two weeks ago, we at the Federal Reserve concluded that our banks would generally remain well capitalized under a range of extremely harsh hypothetical downside scenarios stemming from the COVID event. Even with that demonstrated strength, however—given the high levels of uncertainty—we took a number of prudent steps to help conserve the capital in the banking system.

But he isn’t ready to take a breath of relief:

We know that the financial system will face more challenges. The corporate sector entered the crisis with high levels of debt and has necessarily borrowed more during the event. And many households are facing bleak employment prospects. The next phase will inevitably involve an increase in non-performing loans and provisions as demand falls and some borrowers fail.

This is obviously a space we should all keep an eye on – how well can the post-GFC financial system weather a series of bankruptcies?

Upcoming Data

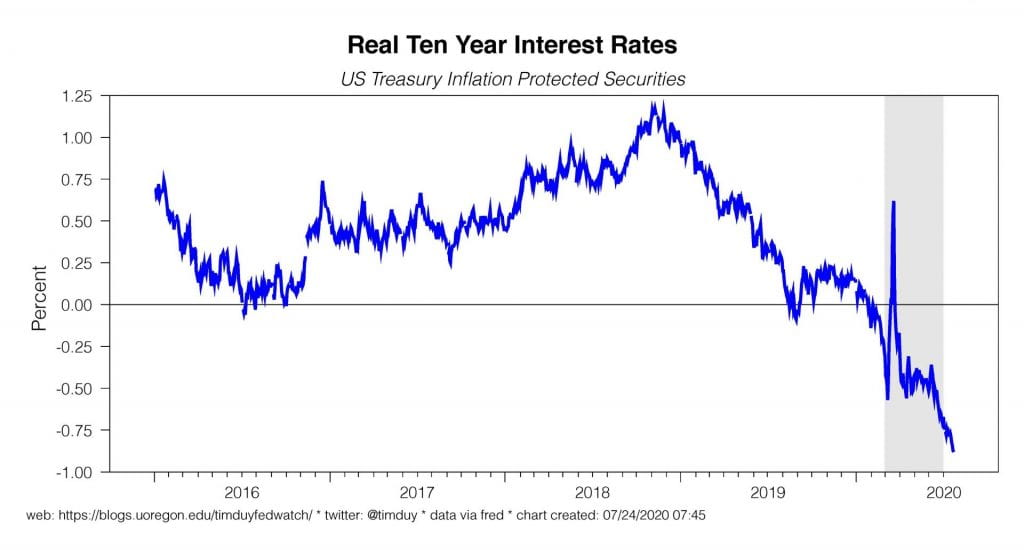

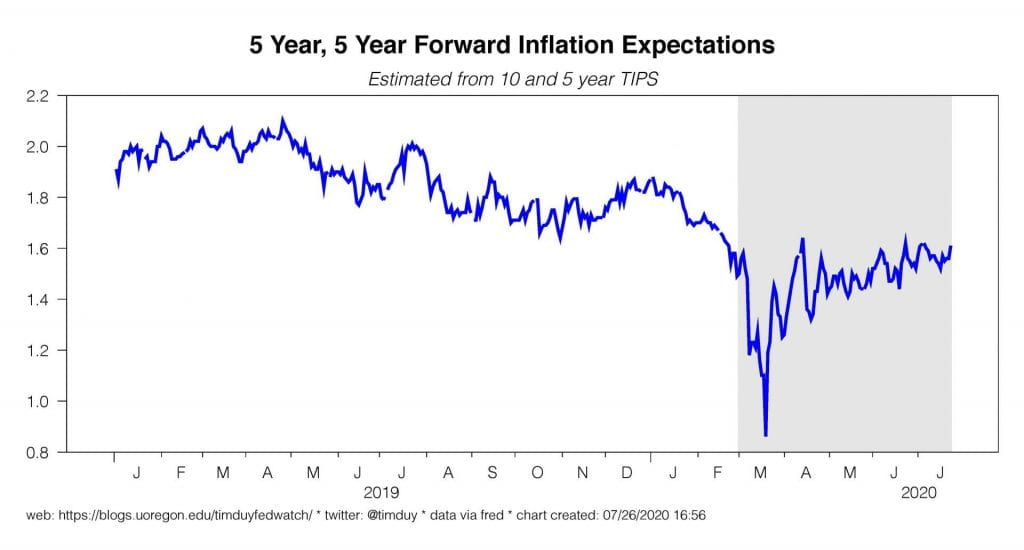

The data flow picks up again this week. Tuesday we get the consumer price index for June; Wall Street anticipates that both headline and core decline by 0.1%. Fed officials also think that deflation will be the challenge going forward; obviously negative prints would reinforce their resolve to maintain accommodative policy. A surprise positive print would be ignored; a series of positive prints would be more interesting but very unlikely. Wednesday brings the industrial production report for June, which is expected to show the sector gained 1.4% as the reopening continued.

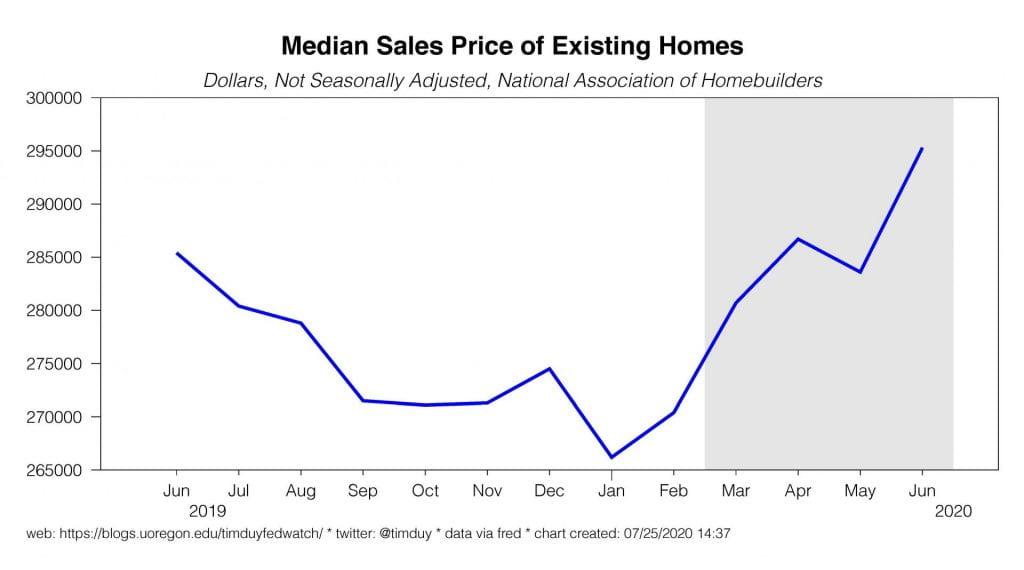

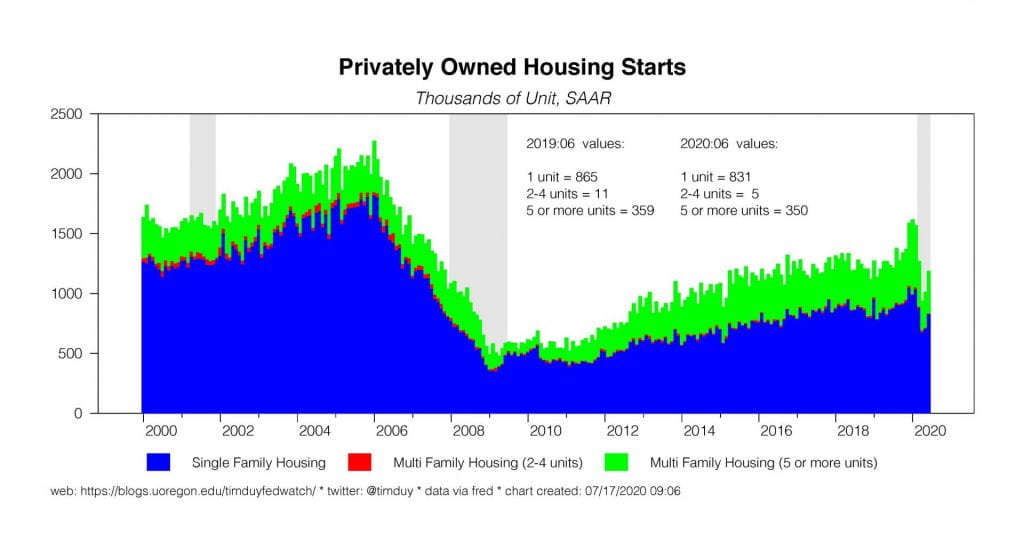

Thursday is a big day. We get the usual jobless claims data; the story there has been one of a very slow decline that is not consistent with a rapid recovery. June retail sales, however, are expect to explode 17.7% higher as consumers continue to make up the ground lost earlier in the year. How much that sticks in July now that Covid-19 cases are on the rise is a big question. We also get the NAHB home builder’s index for July which will be followed by the June housing starts (1.17 million expected) and building permits (1.28 million expected) data on Friday. The housing market has shown considerable resilience; continued strength in the sector would mean the economy would be on firmer footing to rebound when the pandemic eases. The preliminary Michigan Consumer Sentiment number also comes on Friday.

Watch also for the latest Beige Book on Wednesday; it is sure to be depressing. More interesting though will be a speech by Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard titled “Economic and Monetary Policy Outlook.” Sounds relevant.

Discussion

As we move deeper into the second half of the year, we face three big questions. To what extent does the renewed surge in Covid-19 cases slow the economic recovery from the first-wave of shutdowns? How much fiscal stimulus will Congress deliver? What will the Fed do to support the recovery?

There are no easy answers to the first question. Virus numbers are surging across the south and west, but will we see a return to stay-at-home orders or more modest interventions? My instinct is that we will see a mixed strategy of wearing masks coupled with sector specific shutdown such as the closure of bars in Texas, capacity reductions for restaurants, and the shutting of fitness centers. With continued fiscal support though, the economy could weather such a storm. To be sure, growth will be slower than desirable in the near-term, but longer-term growth requires controlling the virus.

How much would this impact Wall Street? In the category of “things that will make people unhappy,” leisure and hospitality is the icing on the cake in the economy. Even though the sector has grown in importance in recent years, it’s valued added was only 4.2% of GDP going into the crisis. The economy can transition away from a shock to this sector. The key is not to allow that transition to translate into cascading shocks to the financial system like occurred after the burst of the housing bubble (see Daly and Quarles above). That’s where fiscal and monetary policy can continue to help. Barring such a major meltdown, I suspect the rally on Wall Street can survive without keeping the bars open.

Given the deteriorating conditions in some states and resulting political impact to Republicans, my expectation is that we see a fiscal support package in excess of the $1 trillion max the White House wants but less than the $3 trillion passed by the House. A key element of any package is that some form of enhanced unemployment benefits will continue, although not with the $600 weekly add-on as before. Via CNBC:

Mnuchin said the White House wants to change rather than extend the enhanced unemployment provision. He did not give details on how it would want to structure aid to unemployed workers.

“You can assume that it will be no more than 100%” of a worker’s usual pay, Mnuchin said. He echoed Republicans who argue the generous insurance deters some people from resuming work because they make more at home than they otherwise would at their jobs.

This is a glass half full sort of situation. Realistically, the full additional $600 a week wasn’t going to last forever. From a market perspective though, a continuation of benefits at 100% for many workers would be supportive. More generally though, if you believe conditions will rapidly deteriorate in (formerly?) Republican strongholds in the next two weeks, I think you should expect the final numbers on the next pandemic response bill to climb higher. Yes, I understand this has the unpleasant implication that a worsening Covid-19 situation is a market positive.

The Fed will continue to lean toward easier policy; see Barkin above. With unemployment expected to remain high and inflation low, the Fed will be under enormous pressure to take further action. I expect that first in the form of enhanced forward guidance and then eventually yield curve control. See what I wrote last week.

There has been some notion of late that the Fed is deliberately moving in the opposite direction by withdrawing stimulus. This idea has gained some traction because the balance sheet has contracted a bit as the repo operations have fallen to zero. I don’t think you should interpret this as an intentional reduction of support by the Fed. It simply reflects better market functioning and more excess reserves such that the repo operations are no longer needed.

Three further points. First, the relationship between the Fed balance sheet and equity prices is murky at best. To the extent that the relationship appears, it is spurious. So I wouldn’t bet that a reduction in the Fed balance sheet resulted in a sustained decrease in stock prices. We already did that experiment. Second, the Fed already committed to sustaining the current pace of asset purchases:

To support the flow of credit to households and businesses, over coming months the Federal Reserve will increase its holdings of Treasury securities and agency residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities at least at the current pace to sustain smooth market functioning, thereby fostering effective transmission of monetary policy to broader financial conditions.

Third, realistically if market conditions deteriorate, the Fed will accelerate asset purchases if they feel necessary. Which altogether gets to the old story of “don’t fight the Fed.”

Bottom Line: If I am cautious going forward, it’s because I am worried that rising Covid-19 cases could turn market sentiment negative. I also worry that another shutdown risks cascading problems in the financial sector. I weigh those concerns, however, against my expectation that the next round of shutdowns will be more limited to sectors that are a fairly small part of the economy, that we will thus not see the general collapse in spending as we saw in the initial phase of the crisis, that we will likely get sufficient fiscal stimulus to limp along at worst, and the Fed will continue its efforts to support the recovery.