If You Don’t Have Any Time This Morning

The pandemic will continue to weigh on the economy but ongoing fiscal support matched by Fed easing will

help ease the pain and support markets.

Bloomberg Opinion

My Bloomberg column last week:

For the Federal Reserve, this time really is different. Having learned a hard lesson in the last recovery — don’t tighten monetary policy too early — the central bank is leaning in the opposite direction. In practice, that means the Fed will not just emphasize actual inflation over forecasted inflation, but will also attempt to push the inflate rate above its 2% target. It’s a whole new ballgame.

Continued here.

Key Data

June retail sales were above expectations and May numbers revised higher. Core sales (excluding gas, autos, food services, and building materials) are solidly above the pre-pandemic trend even though unemployment is in double digits. To me, this is pretty clear evidence that fiscal policy works. Put money in the hands of people who can and will spend it, and they spend it. Looking forward though, renewed shutdowns in states such as California and the general loss of confidence as Covid-19 numbers track higher calls into question the ability of the consumer to sustain this momentum going into the back half of the year. This likely accounts for the softening from 78.1 to 73.2 in the preliminary July release of University of Michigan consumer sentiment. Fiscal policy is crucial here; Congress needs to deliver a package that includes extending enhanced unemployment benefits.

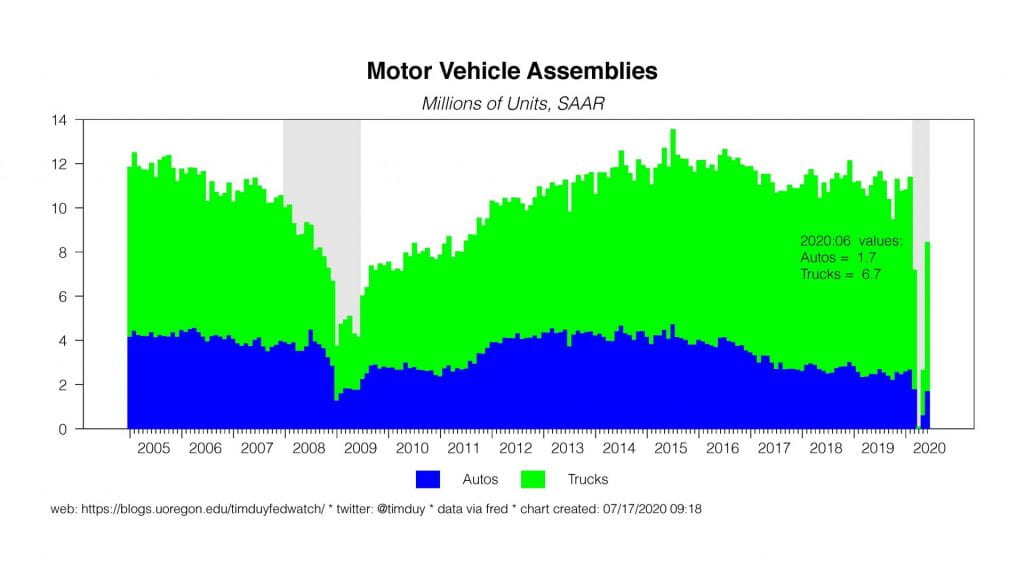

Industrial production jumped 5.4% in June as the lockdowns eased, but remains 10.8% below last year’s levels. The nation’s car manufacturers are ramping up production to meet a rebound in demand. Remember though the initial gains will come most easily. Future gains will be slower.

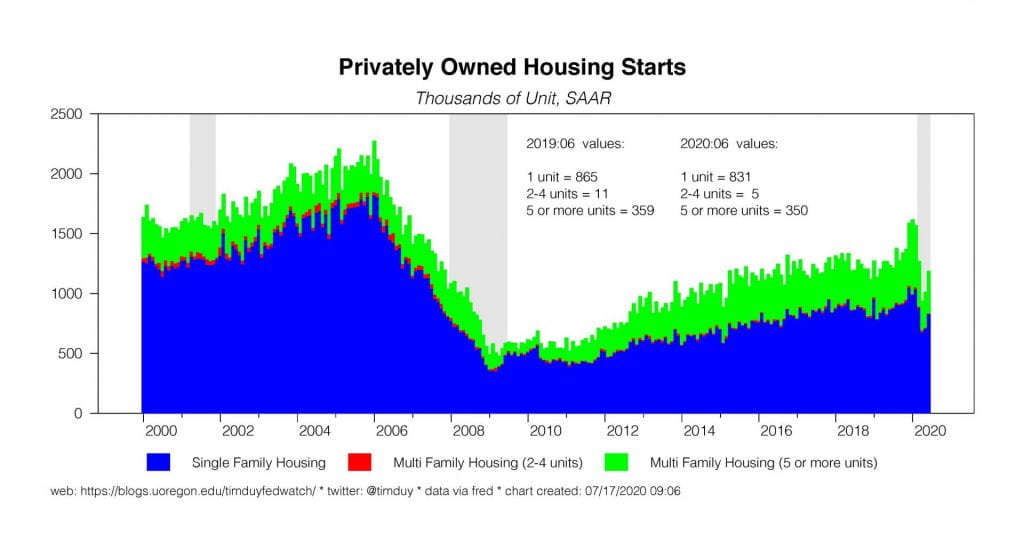

One sector that looks to be having a real V-shaped recovery is housing. Housing starts continued to regain lost ground in June and homebuilder confidence in July to almost its pre-pandemic levels. Unlike the last two recessions, we didn’t head into this downturn with a substantial over-investment in any one sector of the economy such that it was impacting overall activity. If anything, the opposite was the case this time with housing still recovering from lost ground in the aftermath of the last recession while experiencing demographic-driven demand. Housing will provide some much-needed support for this recovery.

The story remains the same as far as initial unemployment claims are concerned. Progress has basically stopped with claims flatlining. Too many firms are realizing that they can’t either stay afloat or retain all their employees given the protracted period of time until the pandemic eases and life resumes to something approaching normal. The case for retaining enhanced unemployment benefits and a new round of PPP remains strong.

Consumer price inflation came in a bit above expectations; see my comments here.

Overall, the data continues to deliver something for everyone. There is enough bounce in the data to see the way forward, there is enough weakness in the data to justify pessimism about the sustainability of that path forward, and there is evidence that fiscal policy works and needs to be sustained.

Fedspeak

Chicago Federal Reserve President Charles Evans came out in support of allowing inflation to drift above 2% before tightening policy. Via Ann Saphir at Reuters:

“I am hard pressed to think of reasons why we would need to move away from accommodative monetary policy unless inflation was well above 2% for an extended period of time, and the economy was just very different from what we are seeing right now,” he said in a virtual event held by the Global Interdependence Center. “That doesn’t seem to be very likely.”

He follows comments by Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard arguing for holding policy steady until inflation reaches 2% in support of overshooting the inflation target:

With the policy rate constrained by the effective lower bound, forward guidance constitutes a vital way to provide the necessary accommodation. For instance, research suggests that refraining from liftoff until inflation reaches 2 percent could lead to some modest temporary overshooting, which would help offset the previous underperformance.

See my comments here for more on Brainard.

While the majority of the Fed is moving toward enhanced forward guidance, some are resisting. Via Greg Robb at MarketWatch:

In a separate interview with Yahoo Finance, New York Fed President John Williams suggested new forward guidance wasn’t needed in the short-term.

Right now, the Fed’s guidance language “is serving us well,” Williams said.

“So we do have some time to think about how we should evolve that guidance as we go forward,” he added.

Williams tends to be a lagging indicator on these sorts of things. Williams also commented on the lack of use of the Fed’s emergency lending facilities, via Reuters:

“This is in fact a measure of success — the existence of the facilities, even in a backstop role, has helped boost confidence to the point where borrowers are able to access credit from the private market at affordable rates,” he said.

The Financial Times also reports on the limited use of the Fed’s programs and notes that it is reducing investor expectations for the growth of the balance sheet. The much-anticipated Main Street Lending program has been a dud. Personally, this is as I expected. This isn’t the Fed’s job and they don’t have any experience in it. Nick Timiraos and Kate Davidson at the Wall Street Journal write that U.S. Treasury officials also worked to limit the attractiveness of the program:

Fed officials generally favored easier terms that would increase the risk of the government losing money, while Treasury officials preferred a more conservative approach, people familiar with the process said.

While Treasury didn’t make the Fed’s job any easier, I think there is a more fundamental problem. Firms with operations that can survive the pandemic are probably both solvent and do not face a liquidity constraint from tight credit. They are already getting the financing they need. Firms that cannot survive the pandemic are insolvent and if you want to sustain them, they need a grant (like what U.S. Treasury Secretary is arguing for PPP loans less than $150,000; see the Wall Street Journal), not a loan, even a long-term, low-interest loan. It’s still a weight on their future profitability and enhances the risk of business failure after the pandemic is over. I suspect the space in-between, firms that both can’t get financing now but are fundamentally solvent and can afford to pay back the loan after the pandemic, is fairly small. Federal Reserve. Chair Jerome Powell though thinks I could be wrong. Via Reuters:

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has said he expects the Main Street Lending Program to come in handy in the fall, when more companies may be financially stressed enough to need to tap it.

Time will tell.

Upcoming Data

Only a handful of major data releases this week. Tuesday we have existing home sales, expected to be 4.86 million for June compared to 3.91 million the previous month. More housing data will come Friday with new home sales for June, 700k expected versus 676k in May. See comments on housing above; this sector has shown remarkable resiliency to date. Thursday we get the usual unemployment claims data. Market participants are looking for initial claims to remain flat at 1.3 million; obviously a substantially lower number would be a ray of sunshine on the bleak labor landscape but such an outcome seems unlikely.

Discussion

The Fed is moving past the emergency response phase of this recession and into the supporting/accelerating the recovery phase. They will continue to fiddle with the lending programs, but I suspect the take-up of those programs won’t accelerate greatly unless the Fed drops interest rate to zero and extends the repayment horizon to 10 or 20 years. I am thinking the Fed will lose interest in the programs sooner or later and adopt William’s position that the lack of use reflects sufficient credit availability. In other words, the Fed did its job saving the financial system; anything else is just a bonus.

It is fairly evident that the Fed is thinking about what comes next. I continue to anticipate the following themes:

- Deflationary forces dominate the landscape, so there is no reason to think about raising interest rates.

- No, really, we aren’t thinking about raising rates.

- Because we know you probably won’t believe us as soon as the economy looks a little better, we are going to have to lock down your expectations with more aggressive forward guidance.

- And, because we kind of screwed up in the last expansion, this time we are not going to pull back on accommodative policy until inflation is actually at 2% and we can be sure we are going to overshoot.

- Overshooting though isn’t part of our policy set yet, but we have been reviewing our strategy and procedures (nudge, nudge, wink, wink).

- If unemployment stays high, we are going to have to do something else, probably yield curve control but not everyone is on board with that yet.

The obvious implication is that interest rates will remain close to zero at the short and medium end of the curve and held down at the longer end. This is going to stress a lot of people out because “interest rates and stocks are telling different stories.” Seriously, like rates haven’t been falling since the mid-80’s while stocks rose? Rates are structurally low now. They don’t need to rise to confirm the gain in equities. Remember what happened in 2018 after the Fed got it into its head they it could raise rates to something closer to “normal.” They had to reverse course.

Another thing to watch for are claims that the Fed is pushing on a string with regards to inflation. I get that story. After all, the Fed didn’t get to 2% in the last cycle, why would we believe them now? And, well, you know, Japan. A couple of responses: During the last cycle, the Fed didn’t really have a strategy for getting to 2% on a sustained basis because they were trying to come in from below, particularly early in the cycle. In effect, the Fed sabotaged itself with excessively tight policy because they were trying to hit exactly 2% not an average of 2%. This was compounded by an adherence to a Phillips curve framework despite persistently low inflation. The Fed is trying to remedy both errors.

Also important is the Fed is sending a signal that they won’t automatically offset fiscal policy. They need to see actual not forecasted inflation. The Fed not getting in the way of expansionary fiscal policy should support inflation, assuming Congress keeps up a rapid pace of deficit spending.

Bottom Line: The virus is dictating the agenda. Until we can control Covid-19, the recovery overall will struggle even if some sectors like housing look promising. We have the fiscal capacity to ease the pain, and will probably continue to use it. The Fed is looking more toward the future and seeing an array of options to support and accelerate the recovery.