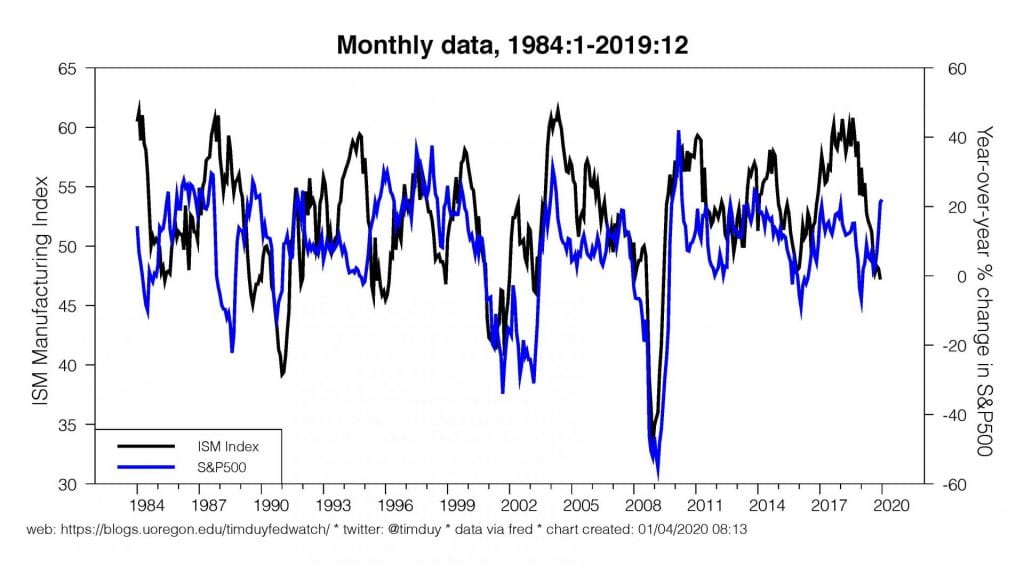

Now that the economy looks to have escaped the clutches of a manufacturing-induced recession, the attention of market bears has turned to that bulwark of spending activity, the American consumer. Not a week passes without a story that households are skating on thin ice and that a consumer-induced recession should be the new focus. In reality though, household spending both stands on a stronger foundation and is more resilient than commonly believed. It’s not the threat to the economy you are looking for.

In a recent Bloomberg article, Lakshman Achuthan and Anirvan Banerji argue that consumer spending power is less than meets the eye. Market participants should approach such fears warily. Consider the opposing view that the consumer is just fine.

First, while nominal wage growth has disappointed, this in part reflects low inflation. Real earning power, in contrast, has been on a tear since 2014:

This, combined with solid job growth and low unemployment both supports the solid consumer confidence numbers we see and provides the basis for spending growth.

Second, remember that retail sales a.) only tell part of the consumer spending story and b.) unless you strip out gasoline sales, energy prices can hide underlining trends. Real person consumption expenditures provides a more comprehensive story of household spending:

With the exception of some gyrations around in 2018, consumption growth has been stuck in the 2% to 3% range since 2016. For all the angst, the underlying pattern of spending has held fairly constant and arguably even a bit high relative to expectations that overall activity settles in close to 2% growth this year.

Third, if households were starved for income to support spending, we would expect the saving rate to be in decline. In fact, the opposite is that case:

The saving rate rebounded after the recession and has maintained an upward trend ever since.

Fourth, while consumers are often described as struggling under the burden of debt, household financial obligations dropped precipitously after the recession and remain near series lows:

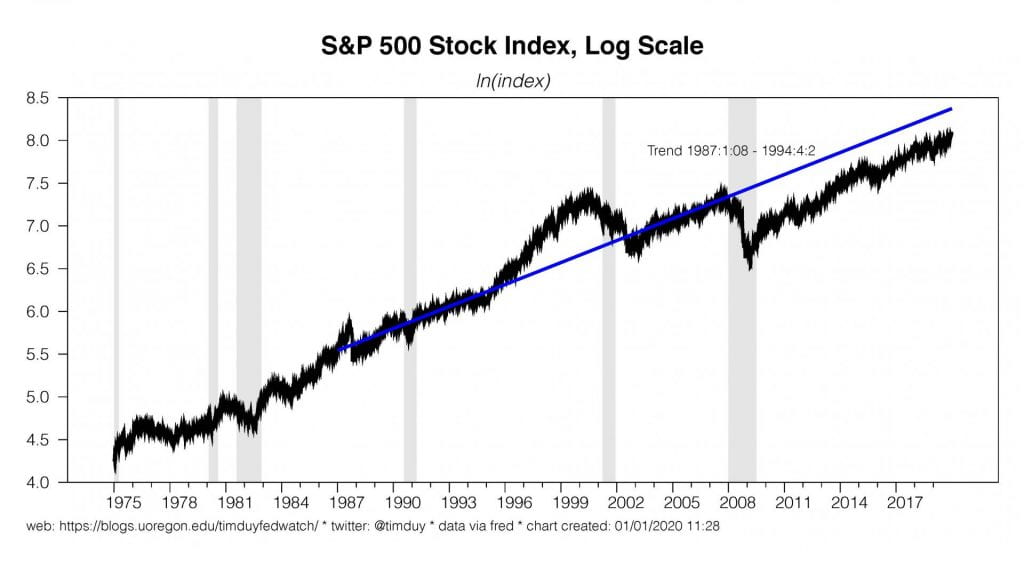

Finally, any talk of consumer spending and recession can’t be separated from the housing rebound experienced this past year:

To be sure, warm weather boosted the December starts numbers, but by that time the reversal of the 2018 downdraft had already occurred. Moreover, homebuilder confidence numbers also confirm the strength of the rebound in the housing market. The housing rebound strikes at the core of the weak consumer story. Panicked consumers on weak financial footing are not going to be driving housing activity higher.

Quite frankly, the rebound in housing should have ended recession talk altogether. While a weak housing market does not always signal a recession (for example, see 1995), recessions are always preceded by housing downturns. Typically, housing starts peak around two years prior to the onset of recession. That means that if housing starts are still climbing, the likelihood of a recession in the upcoming two years is fairly small.

The reality of the situation is many ignore the fundamental strength and resilience of the U.S. economy and hence overestimate the probability of recession. Household are particularly resilient as once spending patterns are set they become very sticky. People don’t change their spending patterns absent a big shock to their income. The big negative shock is generally job loss, which means that a recession is likely to be what causes consumer spending to tank, not vice-versa.

Once you recognize that resilience, you realize why recessions are both rare events and hard if not virtually impossible to predict with any certainty. It takes a large shock to throw the economy into recession. A small shock to an increasingly small sector like manufacturing just lacks to the punch to make it happen.

Bottom Line: I know that it is easy to be seduced by the bearish warnings of market prognosticators. We seem to be hard-wired to be cautious, always worried that we are about to become prey. It is important to keep those fears in check. Years ago I quipped “As long as people have babies, capital depreciates, technology evolves, and tastes and preferences change, there is a powerful underlying (and under-appreciated) impetus for growth that is almost certain to reveal itself in any reasonably well-managed economy.” That lesson is too often forgotten.