Where to begin?

Probably best to first step back to last week’s FOMC meeting. That event concluded with the scene of Powell & Co. running backwards as fast as is possible for central bankers to try to correct the error of the December rate hike. As expected, the Fed downgraded their assessment of the economy and held rates steady. Less expected was the sharp downward revision to the dot plot with now eleven of the seventeen participants anticipating no rate hikes in 2019. The median expectation is for another hike in 2020 and then that’s it for this cycle. Note the median rate path doesn’t even get rates up to neutral. In other words, the Fed no longer thinks containing inflation requires restrictive policy.

That last point resonates as a substantial change to the outlook. The Fed’s models typically don’t work that way. That call for restrictive policy comes from the need to push unemployment to its natural rate to contain inflationary pressures. Those inflationary pressures have apparently disappeared now that the rate forecast has flattened out despite unemployment remaining below its natural rate.

What’s going on here? The persistence of low inflation has finally become too much for the Fed to dismiss, especially now with the economy decelerating. They can’t justify it anymore as a transitory phenomenon so it must be attributable to excessively high estimates of the natural rate of unemployment (which came down again to a now 4.3%) or, more worrisomely, eroding inflation expectations. Powell emphasized inflation concerns in the press conference and acknowledged that the Fed had not met the symmetric inflation target in any convincing way. That’s something of an understatement; if anything, Fed policy has very clearly treated 2% as a ceiling in the actual application of policy.

This from Powell’s press conference is particularly telling:

It’s a major challenge. It’s one of the major challenges of our time, really, to have inflation, you know, downward pressure on inflation let’s say. It gives central banks less room to, you know, to respond to downturns, right. So, if inflation expectations are below two percent, they’re always going to be pulling inflation down, and we’re going to be paddling upstream and trying to, you know, keep inflation at two percent, which gives us some room to cut, you know, when it’s time to cut rates when the economy weakens. And, you know, that’s something that central banks face all over the world, and we certainly face that problem too. It’s one of the, one of the things we’re looking into is part of our strategic monetary policy review this year. The proximity to the zero lower bound calls for more creative thinking about ways we can, you know, uphold the credibility of our inflation target, and you know, we’re openminded about ways we can do that.

I see two big points here. The first is that the Fed suddenly remembered that policy rates remain mired near the zero lower bound. They seemed to forget this point over the last year, too excited by the prospect of raising rates to remember that even at the projected end of rate hikes they would lack the room to mount a traditional response to a full-blown recession. The second point is that fading inflation expectations mean a.) they are “paddling upstream” to hold inflation higher and b.) they have “room to cut” when the economy weakens. My interpretation of this new inflation realization is that the Fed has a fairly low bar for a rate cut; see my latest for Bloomberg Opinion.

Since that meeting, the yield curve continues to flatten and invert with the 10s3mo spread going negative last Friday. An inverted yield curve is a well-known recession indicator. As a market participant, you have a choice. Either embrace that relationship in your analysis or reject it on the basis that any signals from the term structure are hopelessly hidden by the massive injections of global quantitative easing over the last decade.

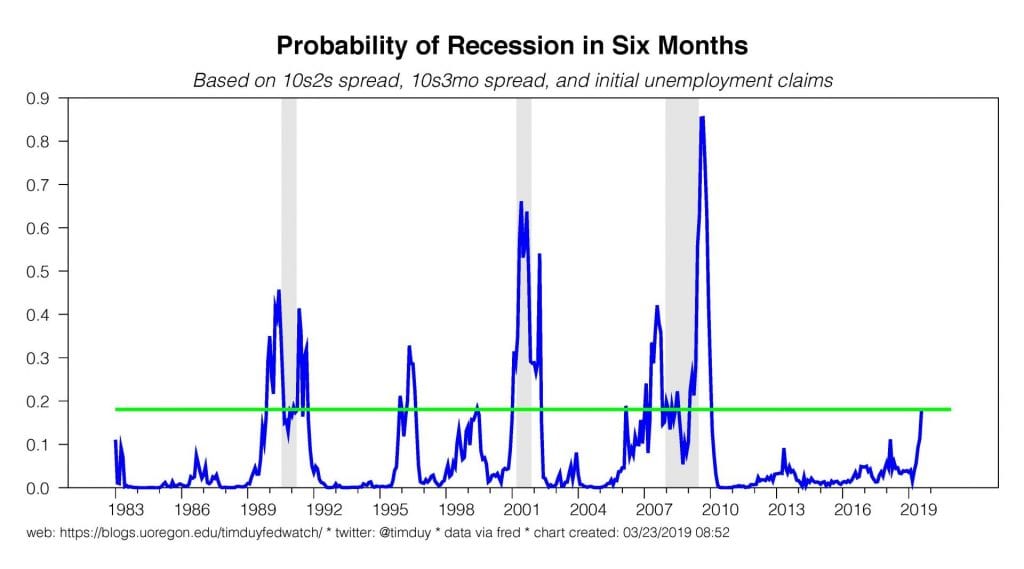

I am going to error on the side of caution and choose the former. Everyone has their pet recession indicator; many are probability models based on some combination of yield spreads and other leading indicators. Most will be raising red flags like this estimate of the probability of recession in six months based on the 10s2s and 10s3mo spreads and initial unemployment claims:

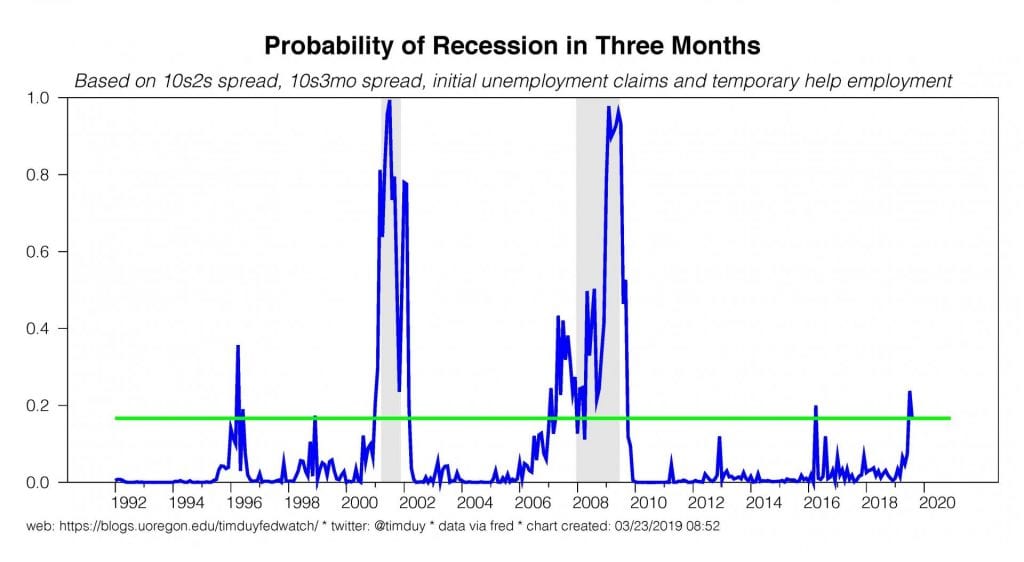

To be sure, the longer into the future, the fuzzier the forecast. If I add in temporary employment claims and narrow the forecast horizon to three months, I get:

In either case I get the same takeaway: The risk of recession has risen to levels that demand attention from the Federal Reserve. In the two cases of similar spikes in the 1990s, a recession was avoided by the rapid response of the Fed in the form of rate cuts. The times that response was lacking, a recession followed.

So now I switch from analyst to commentator: The above leads me to the conclusion that the Fed needs to get with the program and cut rates sooner than later if they want to extend this expansion. Given inflation weakness and proximity to the lower bound, the Fed should error on the side of caution and cut rates now. Take out the insurance policy. It’s cheap. There will be plenty of opportunity to tighten the economy into recession should inflation emerge down the road.

What would delay that rate cut? Data. A yield curve inversion is a long leading indicator. Sure, the data is softer. But soft enough to cut rates? Not necessarily from the Fed’s perspective. Moreover, cutting rates now means admitting the December rate hike was an obvious error. The Fed hates admitting error.

Speaking of errors, the December rate hike is turning into one for the books. Not just on the economic side, but also the political side. I can already hear the howls of the monetary policy community shouting me down with claims of Federal Reserve independence and how nothing has changed in the past two years and that of course the Fed will walk away from the Trump years unscathed. I think that hypothesis is a.) completely wrong and b.) already proven to be completely wrong.

Monetary policy independence is not a law of nature. There is no special 11thcommandment “Thou shalt not interfere with the central bank.” Independence only exists so long as a.) it is an established and followed norm and b.) the central bank continues to deliver results.

The second part is straightforward. The Fed hasn’t delivered on inflation as Powell admitted last week, which by itself is a problem. That problem would be compounded by delivering a recession in an effort to fight a nonexistent inflation problem. You want to stay independent, you have to do your job. After years of watching the Bank of Japan, you would think the Fed had picked up a thing or two on this topic.

On the first part, President Trump shattered the norms last year when he began haranguing the Fed. That didn’t work, or perhaps it even backfired. The Fed would never admit it, but it is hard not to conclude that one factor behind the December rate hike was a perceived need to establish independence. If so, that was a clear case of cutting off your nose to spite your face. On the economic side, there was no cost to taking a pass and coming back to the topic six weeks later. This would have had the political benefit of giving Trump what he wanted. Two birds with one stone, as they say.

Consider the current situation. The Fed is likely to be cutting rates anyways. And now the unimaginable has happened: Stephen Moore is nominated to a spot on the Federal Reserve Board.

I don’t think I need to go into the history here, but if you are new to the game you can check out this by Jonathon Chait and this by Noah Smith. We might as well nominate my cat for that other open spot. And remember the Herman Cain thing? Two years ago, these people wouldn’t have been on the table. Now they are.

You might reasonably say that Moore won’t make it through vetting and the Senate. That’s kind of beside the point. The real issue is the openness with which this administration is willing to place a political operative into the Federal Reserve. Just like any other agency. You should also see it as a blow to Powell’s influence. I suspect that Powell initially had considerable say over the choice of governors. That is how you can explain the nomination of Nellie Liang who, qualified as she is, couldn’t make it out of committee. Now, does anyone think that Powell signed off on Moore? Anyone? Bueller?

My guess is that what happened here is Trump has torn up any agreement he had with Powell to allow the latter to decide on appointments to the Board. And Trump isn’t going to trust Mnuchin, who gave him Powell. So now Trump is going to do what Trump does, and that means nominating people he knows are “his guys.” And once the norms are shattered, can they be rebuilt? What will the next president do?

The game has changed on many fronts, but I am thinking the raw application of political influence is blindsiding the Fed. They should have seen this coming, but I suspect they were too shielded by the central banking community to see it coming.

Bottom Line: I am going to break this into three parts, all market relevant in various ways. First, what I think the Fed is going to do. They are scrambling to recover from the December rate hike and that scramble leaves the Fed positioned to cut rates. Second, what I think they should do. They should cut rates sooner than later; the cost of insurance is low. Third, what I think about the political climate and the Fed. The political climate has changed, and the Fed needs to change with it; don’t buy into the story that the Fed is independent and will walk away from this as the only agency smelling like roses. The failure to adapt is already having consequences, most obviously in who is now considered qualified to lead the central bank.