It’s Christmas, and Mrs. Fedwatch isn’t really keen on me typing away on the computer. Hence, I will need to keep this brief and to the point, at least as much as I can. With that in mind:

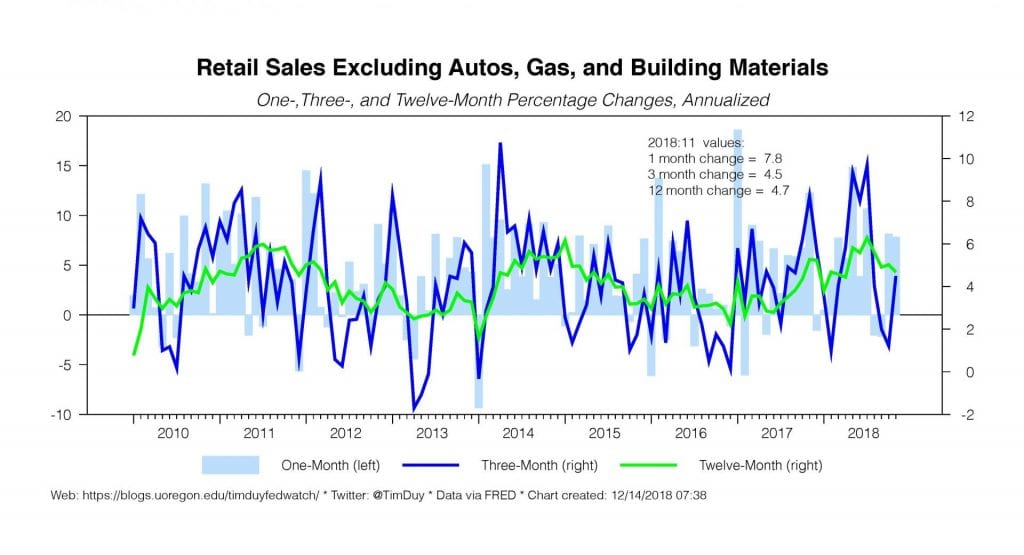

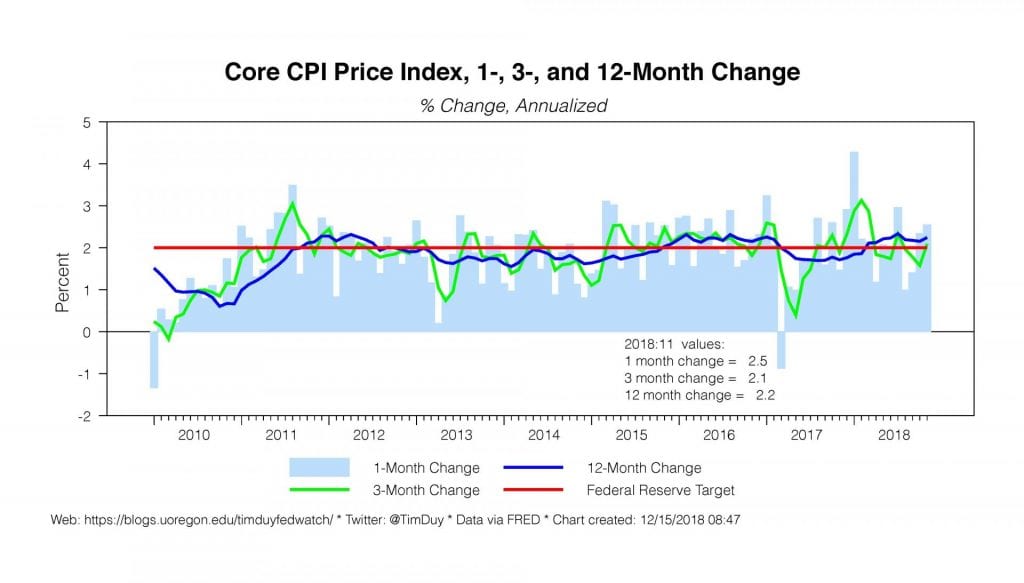

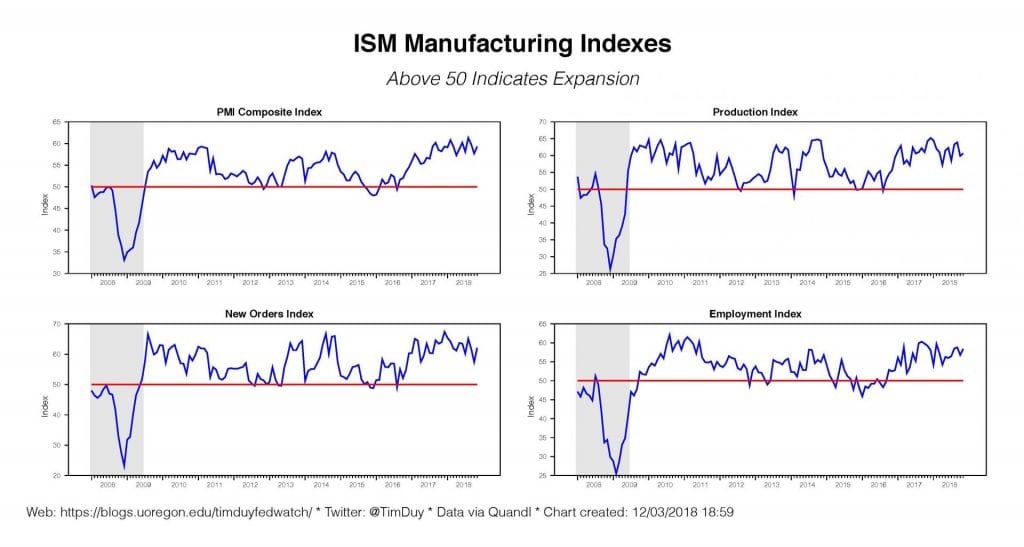

Fed ends the year with a questionable rate hike. The Fed acted as expected and hiked rates last week. The data drove the decision; even with growth slowing, the pace of activity is expected to remain above the rate of potential growth, stoking inflationary pressures. In simple terms, the economy retains too much momentum heading into the economy for the Fed to hold back from pushing closer to their estimate of neutral.

What makes the hike questionable (in my opinion, an error) was that it felt like a model-driven decision much like the December 2015 hike. Both occurred despite market turmoil that had continued too long to be ignored. And both occurred in the context of low inflation. There was no pressing reason for a rate hike other than they insist on defining policy on the back of long-run forecasts and feel compelled to follow-through with that policy.

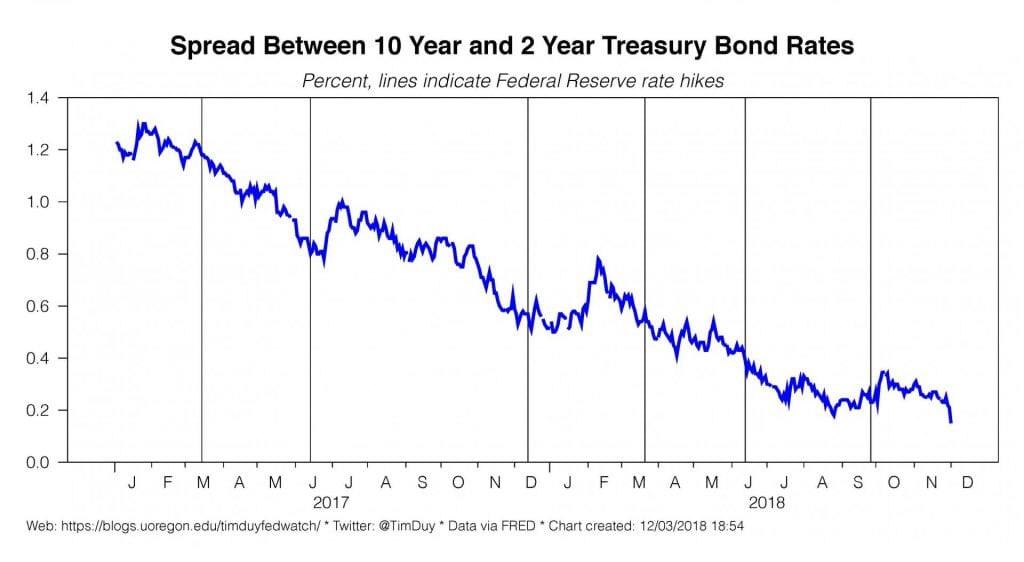

That said, if the hike was an error, it was a recoverable error. I think the Fed will follow the 2016 script and step off the stage for at least the first half of the year if not longer. They now have the yield curve flat as a pancake; continuing to hike rates threatens to invite an outright inversion. Why tempt fate when you can sit back and wait for the lagged impact of rate hikes to make itself evident? They can stop now, stand ready to ease if necessary, and still keep the expansion alive. There is simply nothing in the data that says a recession is right on top of us.

Trump’s war with the Fed was inevitable. We all knew how the Fed would react to a fiscal stimulus shock. A monetary offset was always coming down the pipeline. The Fed never fully embraced the story that tax cuts would induce a supply-side response (a story that looks at odds with the decline in very long-term bond yield back down to 3%), something very clear in the Fed’s forecasts. That monetary offset was destined to anger President Trump.

The Fed isn’t the only thing weighing on markets. I don’t think the Fed is helping with the December rate hike while the forecasts of an intention to tighten policy into the restrictive range only adds insult to injury. That said, equities prices are under stress from a variety of directions: The expected fading of fiscal stimulus (including losing the impact on profits from tax cuts last year), expected slowing growth, tighter profit margins due to tariffs and labor costs, external political factors (Brexit), the US government slowdown, and general Trumpian uncertainty about almost every aspect of US policy. FWIW, it’s reasonable to argue that a bear market without a recession is a buying opportunity.

Trump’s ire with Powell creates a dangerous situation. Trump has reportedly discussed firing Powell as well as Mnuchin, who he blames for hiring Powell in the first place. Even aside from central bank independence issues, it is obviously bad precedent for the President to fire his economic team at the first hint of trouble. What does this say about the reaction of the President to a recession or a real financial crisis? What does this say about the ability of the government to manage the economy in such an event? Nothing good – it says that Trump stands ready to let it all burn down unintentionally because he does not understand policy. It is unquestionably now a real risk for market participants.

I feel we need to place nontrivial odds on the possibility that Trump fires, or at least attempts to fire, Powell. Mnuchin too. Yes, Trump did say nice things about both Powell and Mnuchin on Christmas day. How long is that good will going to last if markets keep slipping? A day? And note Trump’smodus operandi.Threaten to fire repeatedly, say nice things after the news leaks of the threatened firing, and then fire by tweet. Trump never accepts fault for anything, if there is a problem it is always caused by someone else, and that someone needs to be fired. Needless to say, firing Powell would rattle markets.

We don’t know how the Fed would react to an effort by Trump to fire Powell. There is a widely held belief that the President can’t “fire” Powell; at most he can demote Powell from Chairman back to governor. But then Powell’s colleagues could just vote to retain Powell in his role as head of the policy making FOMC. Trump would go ballistic of course and want Powell gone. The Fed could send the whole issue to the courts to be sorted out and, in theory, should they be victorious, enhance the Fed’s independence. But it would come at the cost of protracted uncertainty as the court battle rages.

Trump’s war on the Fed is already damaging the Fed. The Fed will deny vociferously that politics plays any roles in its policy making decisions. That said, central bankers are humans and it seems unlikely to me that they can truly make decisions that are not impacted in some way, even if just subconsciously, by politics. We will never know if Trump prodded the Fed into last week’s rate hike subconsciously; pushing back on Trump would be at least icing on the cake. And if the Fed is forced to cut rates going in the months ahead, they will be accused of caving to Trump even if the data or a Trump-induced market meltdown drives the decision.

Trump is placing the Fed in a no-win situation. I understand that my belief that the Fed has substantial exposure here is someone controversial. I don’t think the Fed can escape the Trump years unscathed. When I say this, the response is that Trump can’t fire the Chair or that he can’t influence the voting FOMC members or that the Chair can just make nice with the Senate.

First, I don’t think Trump cares that he “can’t” fire the Fed Chair. In Trump-world, he hired Powell and can fire Powell. Second, the Senate hasn’t shown much backbone when it comes to standing up to Trump. Third, what wasn’t entirely expected is that Trump can make the Fed do his bidding by creating a crisis that forces a Fed response. Exerting Fed independence in such a situation only puts the economy at risk. Heads they win, tails you lose.

Bottom Line: I not naturally prone to hyperbole, but this whole episode has a distinctly emerging market feel. I of course could be wrong here, but I don’t think that Trump-induced volatility is going to end anytime soon. It will arguably only get worse when a Democratic House of Representatives starts issuing subpoenas. We appear to be caught in a doom loop at the moment with each drop in the stock market bringing about a Trump response that induces another drop in the market. That can’t happen forever of course, but it is not clear that anyone wants to catch the falling knife just yet. We don’t know how long Wall Street can remain under pressure before it bleeds over into Main Street. The Fed can’t stand back and watch that happen; ultimately, they will need to cushion Trumpian uncertainty.

Related reading: