Equity market turmoil continued throughout last week, raising fresh questions about the Fed’s policy path. I don’t believe that Powell & Co. will panic just yet. I suspect they will take a broad view of incoming data and financial indicators and conclude they have little reason to alter their policy path. This will obviously be somewhat disconcerting for already rattled investors.

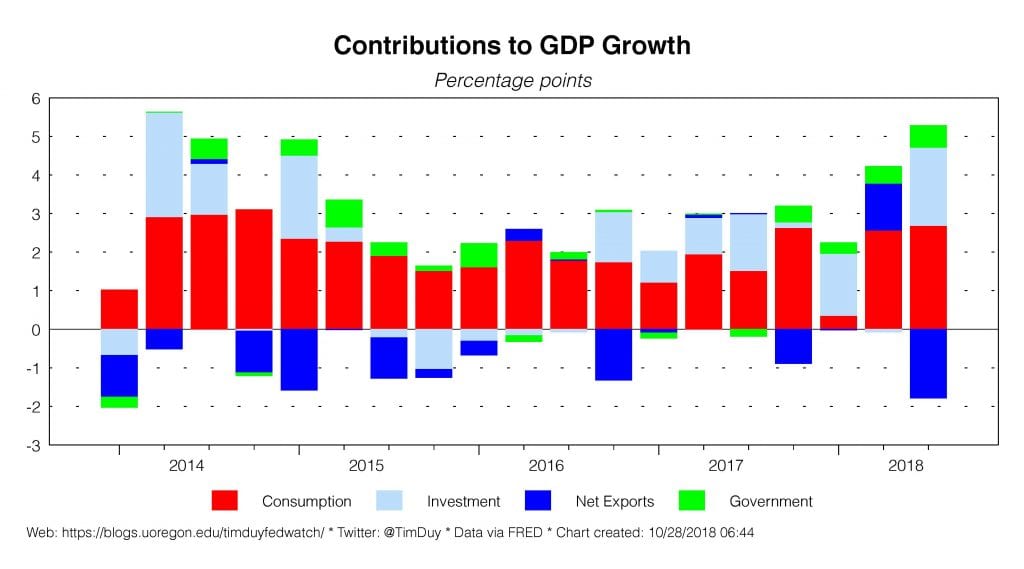

Start with the GDP report. It was generally upbeat with second quarter growth coming in at 3.5%, ahead of expectations for a 3.3% gain. Consumer spending grew at a solid 4% pace. No wonder we are seeing strong confidence numbers. Nothing makes Americans happier than spending, and when they can, they do – in three of the last four quarters, spending growth has registered at 3.8% or higher. With such a sustained, solid pace, I think the Fed would interpret any consumption slowing in the fourth quarter as temporary.

Inventory build contributed 2.1 percentage points to growth, while net exports subtracted 1.78 percentage points. I think we have two things going on here. First, there may have been some inventory building to get ahead of expected tariffs. That would be offsetting – counting as a plus via inventories and a negative via imports. These factors would likely fade out in the fourth quarter. But there was also a -0.45 percentage point contribution from exports, arguably attributable to some mixture slower global growth, retaliatory tariffs, and a stronger dollar. We may be waiting on the fourth quarter to see how all of these factors play out.

A more worrisome aspect in the report was the soft read on nonresidential investment, which contributed a meager 0.12 percentage points, the worst result since the final quarter of 2016. Couple that with the fading core manufacturing orders and you can tell a story that the Trump tax cut boom is fading which – especially when combined with uncertainty created by President Trump’s trade policy – suggests that maybe the capital equipment resurgence is coming to an end.

This is an important space to watch as it cuts two ways for central bankers. On one hand you have a typical demand side story – is this a sign of slowing growth, and, if so, is growth slowing sufficiently to alleviate the inflationary pressures the Fed fears are building? On the other hand, with some central bankers talking up the supply side of the economy as reason to hold rates on the low side, has there been too much supply side optimism?

This is an important space to watch as it cuts two ways for central bankers. On one hand you have a typical demand side story – is this a sign of slowing growth, and, if so, is growth slowing sufficiently to alleviate the inflationary pressures the Fed fears are building? On the other hand, with some central bankers talking up the supply side of the economy as reason to hold rates on the low side, has there been too much supply side optimism?

Housing investment was soft. I don’t have much to add here. It isn’t new – housing hasn’t been a steady contributor to growth for over a year. For those worried about a repeat of the last housing bust, note that the relative lack of substantial rebound in the sector makes for a weak comparison of the two cycles.

Some notable Fedspeak occurred during the past week. Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Richard Clarida presented his outlook and, more importantly, his current economic framework. A few takeaways: First, Clarida sees the risks as balanced and not skewed to the downside as earlier in the cycle. Second, Clarida wants to revive the greatness of the 5-year, 5-year forward inflation guide, an indicator that has been generally downplayed by the Fed in recent years as a measure of inflation compensation, not expectations. Third, Clarida retains his faith in estimates of the neutral interest rates as a policy guide. This places him at odds with other officials such as New York Federal Reserve President John Williams who are downplaying the r-star estimates. Fourth, Clarida sees policy as accommodative and supports further gradual rate hikes. The tone of the speech was on the dovish side in my opinion; barring more significant inflationary pressures, Clarida currently appears likely to resist pushing past his estimates of neutral.

Atlanta Federal Reserve President Raphael Bostic continued to lean hawkish with concerns about what he considers to be a high-pressure economy. He note that high-pressure economies tend to end badly as the Fed tends to follow such periods with a more “muscular” policy stance. Moreover, he worries about the durability of any gains to workers during a high-pressure period, with the implication being that the Fed shouldn’t allow unemployment to fall so much that a disruptive crash is inevitable. More resilient, longer-run gains come not from exceptionally low unemployment, but consistently low unemployment. The upshot for Bostic is that rates need to keep moving higher.

One specific point from Bostic:

Costs are the one area where I have picked up a potential impact from changes in trade policy. Firms in my district are describing an upward shift in their cost structure. However, we have not yet seen a significant pass-through of higher costs into the final consumer space. Inflation remains stable, hovering around the FOMC’s 2 percent objective.

Still, the potential for changes in trade policy to affect the costs of production—through either direct tariffs, supply-chain disruptions, or firms switching to higher-cost routes to import supplies—remains a risk to my inflation outlook.

This matches what we are hearing from firms in earnings reports and is also evident in the Beige Book. There does appear to be substantial cost pressures in the background, and how these pressures evolve is particularly important at this juncture. If they emerge in such a way that the Fed believes they have been too optimistic on inflation, what we are looking at will be fairly typical late cycle dynamic where the Fed feels need to defend their inflation target.

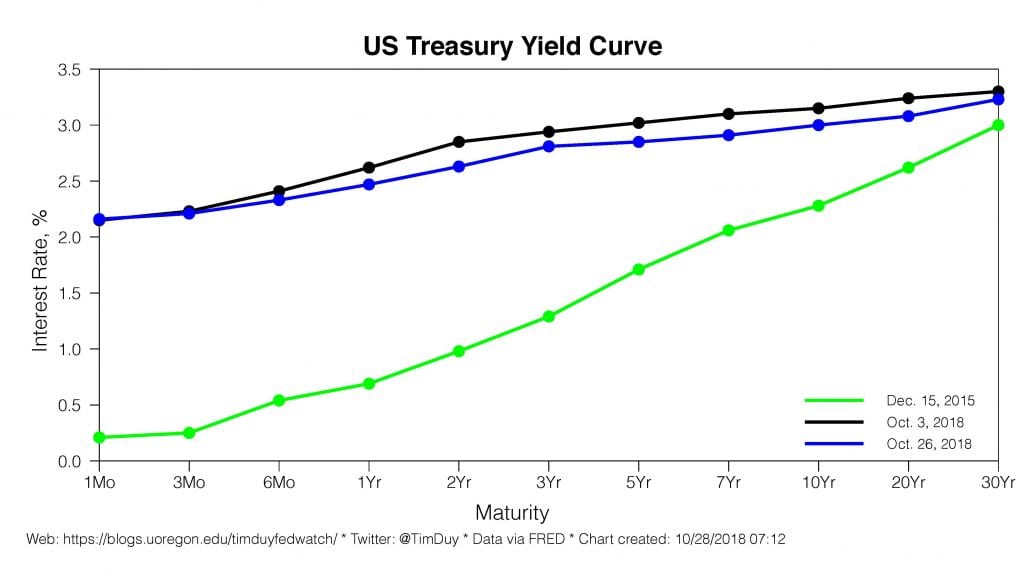

On the chaos in financial markets, we aren’t getting much sympathy from the Fed. I don’t think this should be a surprise. My sense is that central bankers are of course watching the situation, but are nowhere near reacting. I think it is instructive to look at measures of financial pressure in the 2015-16 era. I think the Fed will look at similar indicators and conclude that oil is rising not falling, the dollar is not strengthening as quickly, inflation expectations are not collapsing, and bond spreads remain tight. The general conclusion will be that equity markets got ahead of themselves, and some cooling off is expected and arguably, a good thing for sustaining the expansion.

Treasuries did catch a flight to safety bid. I found it interesting that the long bond, however, held most of the yield gains of recent weeks. That was a bit more resilient that I would have expected if growth concerns were mounting.

Bottom Line: The economy continued to power forward in the third quarter on the back of household spending Flagging investment activity, however, raises some red flags. Overall though nothing to dissuade the Fed from hiking rates. Watch how price pressure evolve in the coming months. If they break higher, a slowing economy will not deter the Fed from hiking rates, at least until it slows enough that Powell & Co. believe the pressure is off – this may require higher unemployment rates. That’s where you need to start more aggressively pricing in the end of the cycle.