This week we head toward an unfathomably bad employment report as we process a grim reality: This is simply no easy way to reopen the economy and an effort to do so before resolving the underlying public health situation may push us back to square one

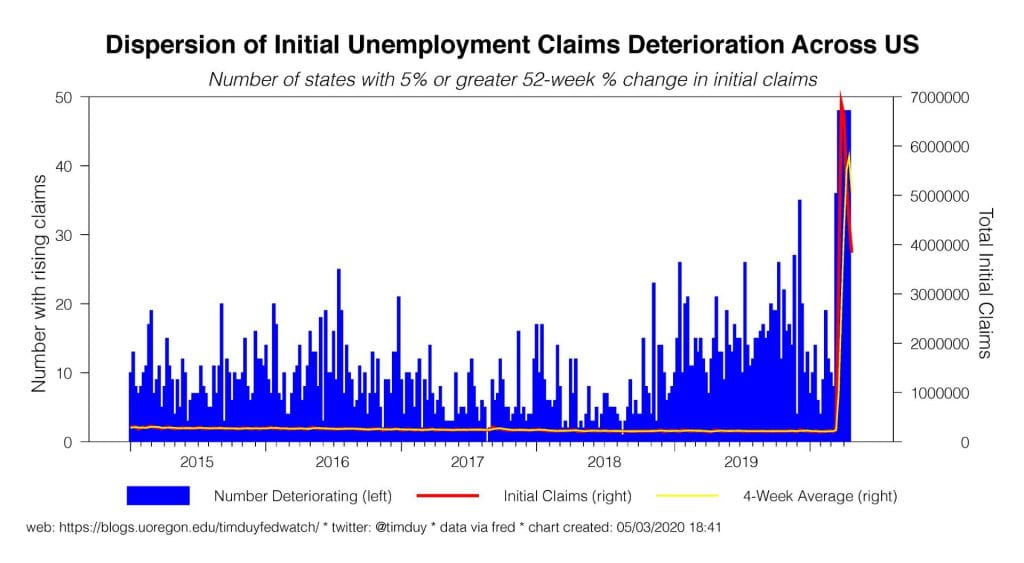

The current situation differs from the past in that we deliberately closed large portions of the economy in an effort to contain the spread of Covid-19. The incoming data should thus be fairly predictable. To be sure, it hasn’t disappointed. Initial unemployment claims were without a doubt the harbinger of the data flow to come. While we look to be on the downside of the initial claims surge, that is kind of the definition of “cold comfort” when the level is ridiculously high:

If you can’t leave the house, you can’t spend. You can’t spend, the consumption numbers collapse:

I thought it was such a clever idea to annualize all of my charts to better connect the monthly changes to the annual changes. Of course, at the time I would not have anticipated an event that make it seem as if consumption had fallen by more than 50%. Annualized numbers aren’t much help here as in the short-run as they overstate what is already a bad enough situation; the 5% year-over-year decline is recessionary all on its own.

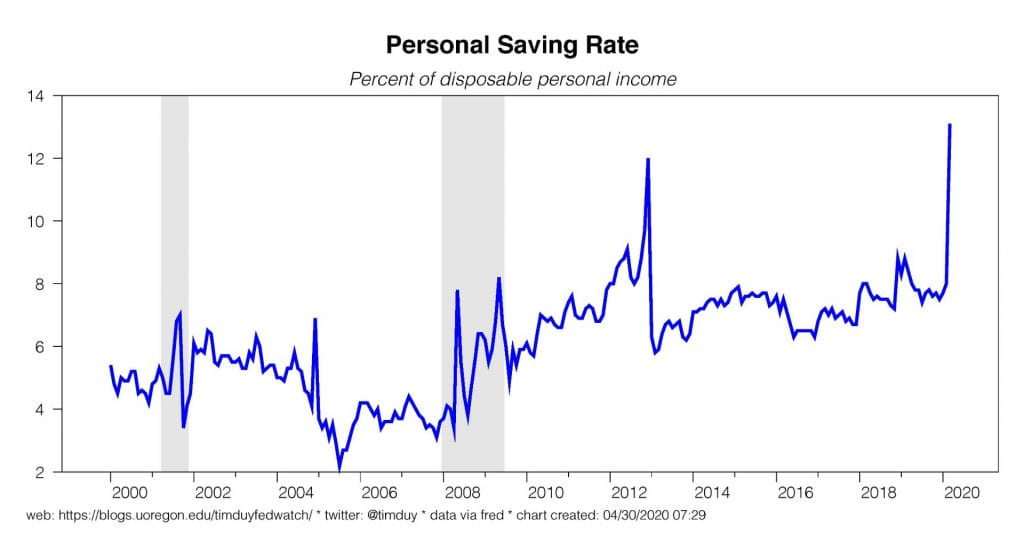

The saving rate jumped in March as should have been expected:

The spending collapse outweighed the decline in income. This should not be taken on face value of evidence that a massive surge of pent-up demand awaits us. The saving rate as calculated here is simply a residual of income minus consumption; the surge in the saving rate is an artifact of the income and consumption patterns, not a deliberate choice on the part of consumers. In subsequent months, we will see incomes collapse which will drive the saving rate back down. Yes, there will be pent up demand that is unleashed when the social-distancing restrictions ease, but it will be far more modest than suggested by this number.

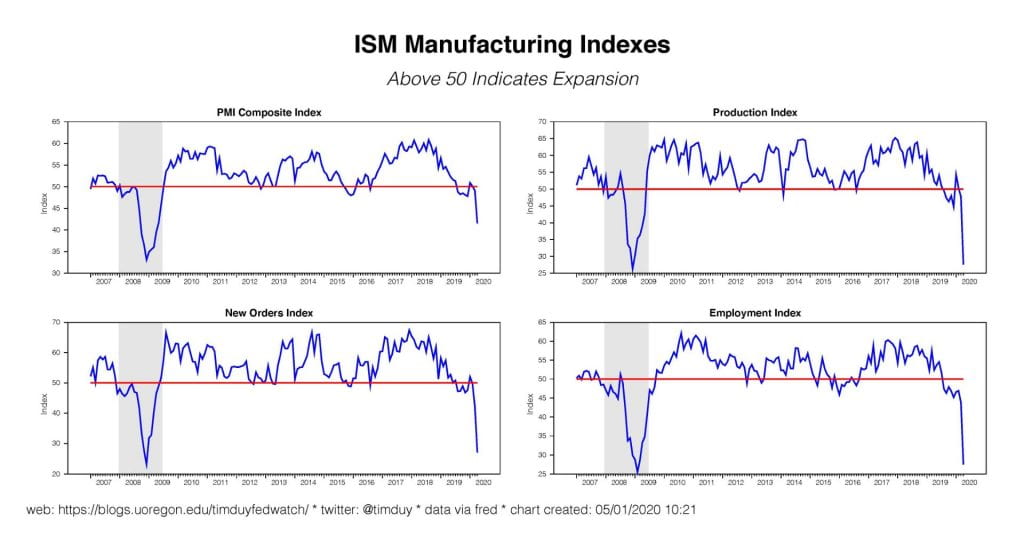

Likewise, manufacturing activity took a hit:

Beware that a declining speed of supplier deliveries boosted the headline number. Typically, slower deliveries indicate tight demand. Now it reflects supply chain disruptions. There was a touch of deflation in core-prices:

Last week, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell expressed confidence that deflation would be kept at bay:

I would say, as long as inflation expectations remain anchored, then we shouldn’t see deflation.

I am somewhat less confident, while there is a resurgence of inflation fears among some segments of the finance community. Hard for me to see that outcome given the demand shock ripping through the economy.

OK, the current situation is bad. Very bad. Still, eventually we need to move forward, right? Yes, but what will “forward” look like? It is becoming increasingly evident that “forward” will be slow and choppy. Restarting the economy looks increasingly difficult with each passing day

We are getting a glimpse of that reality as states trying to reopen are quickly learning that it isn’t about flipping a light switch. From the Wall Street Journal:

The early experience in South Carolina and other states is a sobering portent for the country as a whole, suggesting it will take more than lifting lockdowns for economic activity to rebound.

It also illustrates the limits of policy makers’ influence when residents’ and businesses’ behavior depends on their own perceptions of risk. In many places, activity shut down long before governors issued their stay-at-home proclamations. The data so far suggest it will take a while after orders are lifted for the economy to pick up again.

You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.

Ultimately, I decide when and under what conditions I begin to normalize my behavior. I shut down before Oregon’s Governor Kate Brown ordered it, and I would stay shut down if she reversed those orders anytime soon. The parts of the economy that survive on low margins and high volume – think leisure and hospitality – simply can’t stay up and running if any sizable fraction of people remain unwilling to resume their pre-virus activities. Sure, you can let a restaurant open at 50% capacity, but how many can survive at 50% capacity? Not a lot.

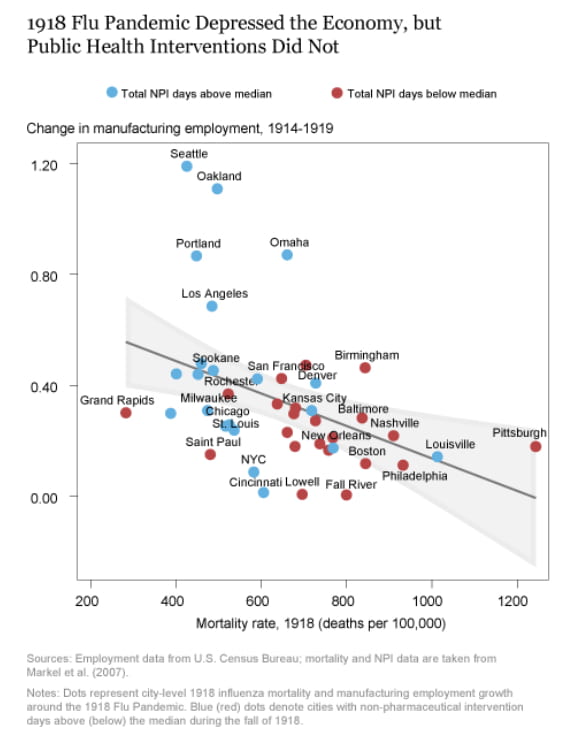

Effectively, the economy is contracting to a new equilibrium that incorporates the threats posed by the virus. We can’t get back to the old equilibrium until we manage those threats. Managing those threats requires a strong, coordinated public health response. The public health policy is the economic policy.

Unfortunately, the U.S. lacks a coordinated, national response. The response is piecemeal, state-by-state. Some states, such as South Carolina above, are learning the hard way that you can’t restart the economy simply by waiving a magic wand. Moreover, such states also risk a resurgence of the virus by reopening prematurely; this would like result in a new round of closures. The first round of closures would become a completely wasted effort.

The lack of a sufficient public health response also means that the Federal aid to support the economy will prove to be insufficient. The intention was correct, but the execution flawed. We see this most clearly in the unemployment insurance situation. The state systems where not capable of handling the influx of applicants and the enhanced benefits will end too soon if the economy is unable to rebound.

The SBA lending program similarly suffered from an overwhelming number of applicants. Moreover, firms are finding it difficult to spend the money due to the requirement that 75% of loans must be used for payroll within 8 weeks: see the Wall Street Journal here. If the economy remains weak, then firms will find they need to fire the rehired workers, so why pull your employees off of unemployment now? The loans will prove most beneficial to firms that didn’t lay off people in the early stages of the shutdowns and could limp along without the loans to begin with. For other firms, the loans can’t compensate for a lack of customers.

What to do? We need a coordinated public health effort sufficient to mitigate the risks of the virus enough to provide a reasonable degree of confidence among the general public, extended aid for workers and firms that is less restrictive and phase out on the basis of economic outcomes not time, and aid for state and local governments. The longer we delay these actions, the less robust will be the recovery.

Bottom Line: The public health response is the most important economic policy. The economy will be stuck at a lower equilibrium until the public is confident in their ability to manage the personal safety. Until that point, we limp along at sub-optimal levels.