Initial unemployment claims edged up last week. This is disappointing but the data is damaged by the failure of California to update its numbers. And as I have argued, the initial claims data appears to have overstated the severity of the recession. I want to explore that point a bit further.

To begin, I have a particular reason to be cautious about the initial claims data. At least in Oregon, following that data resulted in a fairly consequential forecast error. From the latest Oregon Revenue Forecast:

At the time of our previous forecast, the only data available was the tidal wave of initial claims for unemployment insurance. To date Oregon has received more than half a million initial claims. Now, these claims always overstate the level of job loss in the economy, and fail to capture any job gains occurring. However given the sudden stop nature of the pandemic and ensuing recession, our office believed the relationship between the increase in initial claims and job loss would be stronger than usual. This turned out to not be the case. In recent weeks the Oregon Employment Department found that 200-300,000 of the initial claims correspond to categories that are unlikely to result in job loss, at least as measured in the standard monthly employment reports. Such categories include those receiving Work Share, those filing incomplete, duplicate, or invalid claims including PUA claims filed in the regular program, or claims that ultimately resulted in zero or just one week of benefits claimed. The upshot is while our office forecasted job losses of around 20 percent, in reality Oregon lost 14 percent at the nadir in April, and 12 percent for the second quarter as a whole. As such, the initial severity of the recession was not nearly as bad as expected. The economy is tracking considerably above forecast today given the relative starting point for the recovery is higher

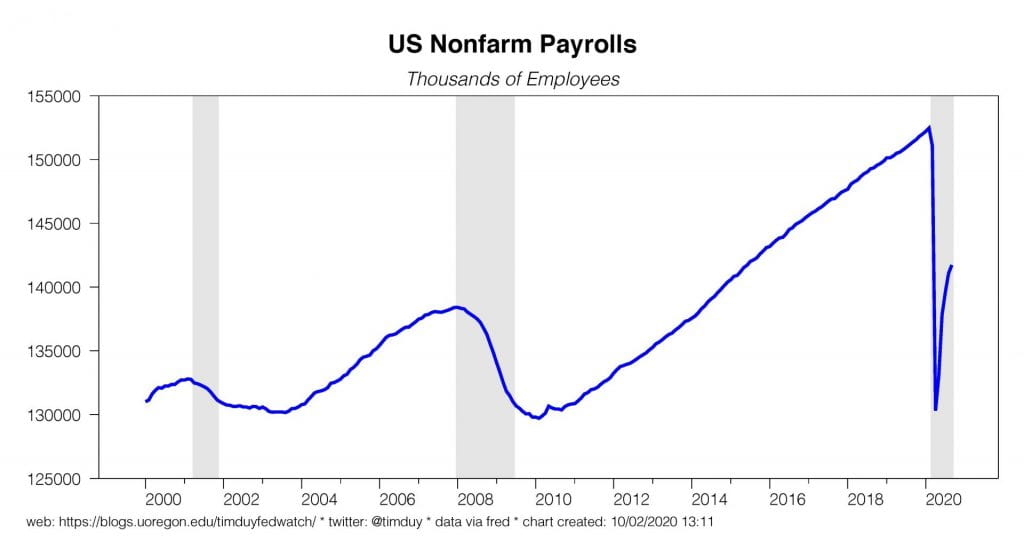

That’s Oregon. What about the U.S.? I find it surprising that I have seen no commentary regarding the fact that the U.S. recorded roughly 50 million initial claims in the four months between March and June yet that translated in a peak to trough drop of just 22 million jobs. The pace of rehiring was either remarkably rapid or it should be a red flag that something is broken.

Consider the scatterplot of claims versus job growth over the past three business cycles, 1990:1 – 2020:1:

Eyeballing the data you can see a kink in the relationship. At around 350,000 claims (average over the month), the level of claims is essentially irrelevant to job growth (measured as y-o-y change). It doesn’t make sense to fit a line through the entire data set, so instead I regressed only on periods where claims exceed 350,000, 152 observations out of 362 total. I think it passes the smell test (R-squared is 0.73):

Now let’s extend the fit to the data since the pandemic recession began:

Using the pre-pandemic relationship, the April pace of claims of roughly 5 million a week should have translated into a year-over-year job loss of 150 million. That’s crazy and didn’t happen. The level of claims has persistently overstated the extent of the actual job losses; the degree of deviation from the past trend has lessened over time although still remained in September. The estimated job loss based on claims was 14.6 million compared to September 2019; the actual loss was 9.6 million.

I can largely eliminate the problem in September by using just data from recession months:

I get a better fit, R-squared is 0.87, but there are only 32 observations and probably isn’t an accurate projection for the last few months as the economy is no longer in recession. I know, I can hear the howls of protest already, but a recession is not all periods in which the economy is below potential but instead only periods where output is falling. Monthly indicators turned in May:

Bottom Line: I don’t know what happens going forward. Maybe when California fixes its data we learn that claims kept dropping in October. Or maybe the employment data is revised downward on a massive scale. Or maybe job growth just flattens. What I am fairly confident of is that the claims data resulted in a degree of pessimism about the economy that was clearly unwarranted. Is the pace of layoffs still elevated relative to last year? Almost certainly yes. But I am not confident layoffs are as high as the initial claims numbers suggest.