The US economy continues to power forward, providing central bankers with plenty of reasons to keep hiking rates. But with inflationary pressures held at bay, the pace of rate hikes remains gradual. Rate hikes will likely continue until policy turns from accommodative to restrictive, but the Fed has jettisoned the “r-star” guide, leaving us to pick apart the data to determine when policy rates have moved to neutral and beyond.

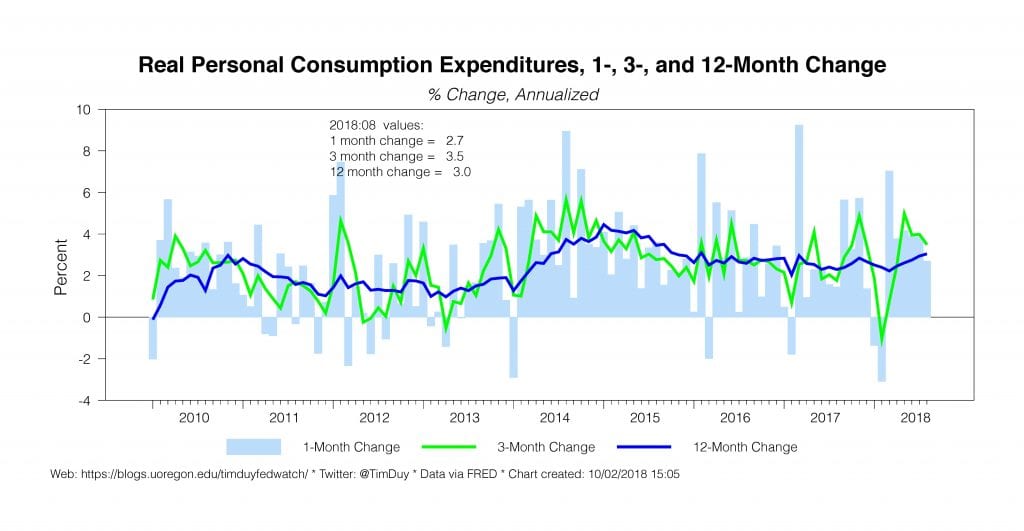

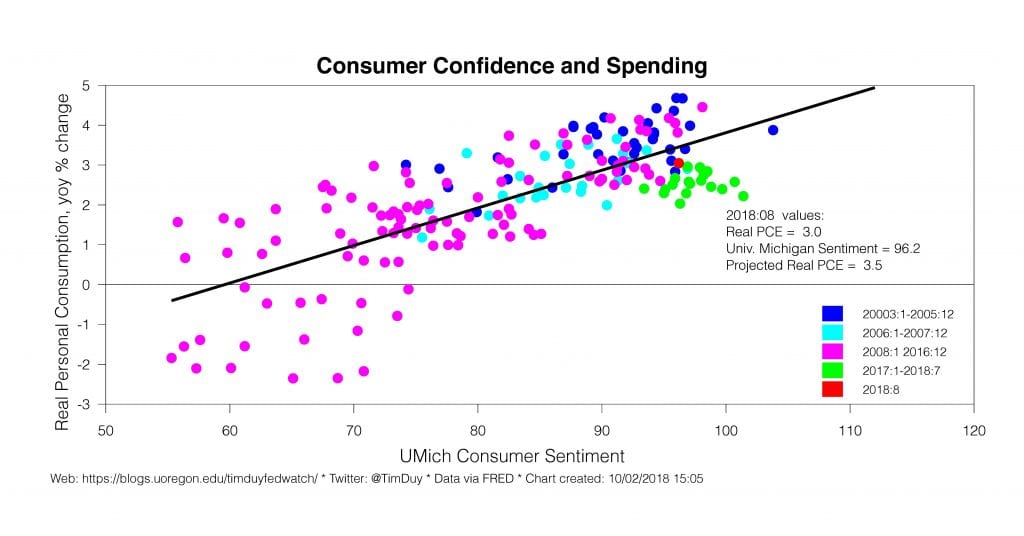

Recent data follows a familiar pattern of general strength. Household spending in August was up 3% compared to a year earlier, the fastest pace since 2016. The spending looks likely to continue on the back of solid job growth. Indeed, consumers appear quite pleased with the situation. The University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment measure rebounded in September while the Conference Board confidence number rose to an 18-year high.

That said, the disproportionate happiness of Republican respondents may render the confidence measures less useful as a guide to consumer spending. Since 2017, spending growth has consistently fallen short of forecasts based on confidence numbers – it is unusual to see persistent one-sided errors in the forecast. That said, even discounting the confidence numbers accordingly still leaves behind a solid pace of spending growth.

Manufacturing activity remains impressive. The ISM manufacturing survey components continue to track along near cycle highs. Interestingly, the export and import components, though off their highs, don’t appear consistent with the anecdotal comments reflecting concerns about the trade situation. In other words, the tariff concerns remain a speedbump rather than a roadblock. And hopefully the new trade agreement with Canada and Mexico will help ease some of the concerns.

While the economy keeps chugging along, inflation remains contained. Although core-PCE inflation met the Fed’s target in September, the monthly gain was a meager 0.4% annualized, pulling the 3-month change down to 1.3%. A tight economy has yet to induce widespread inflation pressures. Nor have tariffs changed the inflation picture yet. Nor have firms used tariffs as an excuse to raise prices aggressively. Now, that doesn’t mean we should count on low inflation going forward, just that some of those prediction may have been premature. Firms may just delay prices changes until the end of the year, at which point we might again see outsized seasonal inflation gains.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell gave a glowing review of the economy when he took to the podium in Boston:

From the standpoint of our dual mandate, this is a remarkably positive outlook. Indeed, I was asked at last week’s press conference whether these forecasts are too good to be true–a reasonable question! Since 1950, the U.S. economy has experienced periods of low, stable inflation and periods of very low unemployment, but never both for such an extended time as is seen in these forecasts.

That doesn’t mean the Fed is gearing up to kill the expansion on the basis that an inflationary outbreak is imminent. That seems unlikely given the apparent flatness of the yield curve. Instead, the Fed is trying to manage the risk that inflation could emerge. Powell takes the middle ground here:

At the risk of spoiling the surprise, I do not see it as likely that the Phillips curve is dead, or that it will soon exact revenge. What is more likely, in my view, is that many factors, including better conduct of monetary policy over the past few decades, have greatly reduced, but not eliminated, the effects that tight labor markets have on inflation.

Powell credits central bankers with controlling inflation expectations, which in turn is a key element in flattening the yield curve:

When monetary policy tends to offset shocks to inflation, rather than amplifying and extending them, and when people come to expect this policy response, a surprise rise or fall in labor market tightness will naturally have smaller and less persistent effects on inflation. Research suggests that this reasoning can account for a good deal of the change in the Phillips curve relationship.

Ultimately, Powell balances the threat of moving too slowly and risking that inflation expectations rise against the threat of moving too quickly and killing the expansion. The result is by now a familiar policy stance:

Our ongoing policy of gradual interest rate normalization reflects our efforts to balance the inevitable risks that come with extraordinary times, so as to extend the current expansion, while maintaining maximum employment and low and stable inflation.

Gradual rate hikes will continue. When will they end? That of course is the million-dollar question. Neither the terms “neutral rate” or “r-star” enter Powell’s speech, a guidepost that he began tossing aside in September and that New York Federal Reserve President John Williams blew up last week. Given the expected path of the economy, though, we can anticipate that policy rates will rise until they become restrictive. Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren predicted such an outcome in his speech Monday:

Federal Reserve policy makers will likely need to move interest rates gradually from a mildly accommodative stance to a mildly restrictive stance

Of course, this information is plain to see in the SEP forecasts. Restrictive policy is the method by which the Fed nudges up the unemployment rate to a level they believe consistent with continued low inflation. And something to watch – in those forecasts, policy remains restrictive even as growth slows.

Bottom Line: Any dovishness you read in the Fed still reflects only that they expect to maintain a gradual pace of rate hikes, likely until policy turns restrictive. In other words, not accelerating the pace of rate hikes. For the latter, they would need to see an inflationary situation that is just not evident.