Prologue

In an earlier piece I documented the Federal Reserve’s failure to consistently hit their 2 percent inflation target and suggest a corrective policy change. Here I explore some of the confusion around the current framework and consider how the Fed can be pursuing a symmetric inflation target yet not see symmetric policy outcomes.

Introduction

The Federal Reserve’s much anticipated conference on strategy, tools, and communication will soon be upon us. Will the conference yield any groundbreaking changes in the Fed’s policy approach? Probably not. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell set a low barfor the outcomes of this year’s strategy review, stressing the likely results would be “evolution not revolution.”

This of course doesn’t mean the Fed will not make meaningful progress. One place where progress should be obtainable is an improvement in the communication of its inflation target. The messaging around inflation and the inflation target has been muddled.

Specifically, the Fed does not appear to be properly communicating its interpretation of the “symmetric” inflation target. The operational meaning of “symmetry” has become confused. The Fed should more clearly differentiate between policy actions and policy outcomes when describing its symmetric target. Under the current framework, symmetric policy responses to inflation deviations do not necessarily imply symmetric policy outcomes in which observed inflation is equally distributed around 2 percent, particularly in the short-run.

Market participants, however, appear to believe that properly executing a symmetric inflation target should yield outcomes of 2 percent average inflation. Fed officials appear to believe this as well. Upon reflection, I don’t think this is necessarily true; persistent deviations from 2 percent are acceptable and possibly even likely within the context of the Fed’s current strategy. The Fed needs to either clearly explain that a symmetric inflation target should not be equated with 2 percent average inflation outcomes or change something about its strategy to bring about 2 percent average inflation outcomes.

The latter option could be achieved with a shift to an “average inflation target” that is version of price level targeting. This may be a bridge too far for the Federal Reserve; this would be more revolution than evolution.

The Original Meaning of Symmetry

Commenting on the December 19, 2018 FOMC meeting, St. Louis Federal Reserve Economist David Andolfatto observed:

…it occurred to be that people might be mixing up the notion of a symmetric inflation target with a price-level target.

If the Fed were to generate symmetric inflation outcomes around a 2% target, those outcomes would be operationally equivalent to a price level target. Andolfatto explains, however, that a symmetric inflation target refers not to the outcomes, but instead “implies the Fed should feel equally bad about inflation being 50bp above or below target.” Then Vice Chair Stanley Fischer noted in the January 2016 FOMC meeting, the time at which the Fed added “symmetry” to the inflation target, that this definition of symmetry was consistent with the understanding of Fed officials:

The proposed revisions would clarify that the Committee viewed its 2 percent inflation goal as symmetric. In presenting the revised statement on behalf of the subcommittee on communications, Governor Fischer pointed out that, in a discussion of the statement in October 2014, participants had expressed widespread agreement that inflation moderately above the Committee’s 2 percent goal and inflation the same amount below that level were equally costly. He noted that the proposed language was intended to encompass situations in which deviations from the Committee’s inflation objective were expected to continue for a time and had the potential to affect longer-term inflation expectations.

Operationally, the symmetry is in the Fed’s response when faced with deviations from target – they treat positive and negative moderate shocks of equal magnitudes with equal but opposite policy responses.In this framework, a 20 basis point shortfall of inflation relative to target will prompt a policy easing of equal magnitude to the policy tightening triggered by a 20 basis point excess of inflation relative to target.

Importantly, symmetry does not imply an effort on the part of the Fed to overshoot or undershoot the target to compensate for past errors. The Chair Janet Yellen made this clear at the March 2016 press conference:

SAM FLEMING. Sam Fleming from the Financial Times. Can I just follow up on this inflation point? Because the numbers have been ticking up, as you said—somewhat, at least. And we’re also, as you said, also at a point where we have quite close to full employment. Is there a risk that we’re heading for an overshoot in inflation, and is there, given the greater symmetry the Fed has been flagging up, in terms of its inflation target, a greater tolerance for a modest overshoot, especially given the long period of undershoots that we’ve been through?

CHAIR YELLEN. So I want to make clear that our inflation objective is 2 percent, and we are projecting a move back to 2 percent. And we are not trying to engineer an overshoot of inflation, not to compensate for past undershoots, so 2 percent is our objective. But it is a symmetric objective, and we certainly don’t seek to overshoot our objective. But some undershoots and overshoots are part of how the economy operates, and our tolerance for those is symmetric with respect to under- and overshoots.

Stepping back to 2016, the Fed’s intentions look fairly clear. Symmetry had a very specific meaning regarding the Fed’s reaction to overshooting or undershooting the inflation target. It simply meant they cared, or would react to such deviations in an equal manner. At no point did they intend that they would deliberately overshoot or undershoot the target to make up for past deviations.

Importantly, this should have comforted market participants that the Fed would not overreact to a shock that pushed inflation above target. But then something happened that the Fed probably didn’t expect – there was no such positive shock. The shocks were all negative. That outcome set the stage for the increasing confusion about the meaning of the symmetric inflation target and what it meant for Fed policy.

It’s Not About Inflation, It’s About the Inflation Forecast

Since the Fed created the inflation target in 2012, inflation has remained on average below inflation. This gave rise to the view that the 2 percent target was really a ceiling. The Fed sought to lessen this concern with the emphasis on the inflation target being symmetrical. Participants in the January 2016 FOMC meetingwere fairly optimistic regarding the gains from symmetry:

…they judged that the revisions were important because they would clarify the symmetry of the Committee’s 2 percent inflation objective and communicate to the public that the objective was not a ceiling. Participants also noted that the proposed new language indicating that the Committee would “be concerned if inflation were running persistently above or below” its 2 percent objective would not require that participants hold similar views about inflation dynamics; in addition, the proposed language would not specify the stance of monetary policy in such circumstances but would afford the Committee appropriate flexibility in tailoring a policy response to persistent deviations from the inflation objective. Moreover, participants generally agreed that the proposed new language should be interpreted as applying to situations in which inflation was seen as likely to remain below or above 2 percent for a sustained period.

St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard, however, saw a potential problem:

…one participant judged that the proposed language could be read as referring to current and past deviations from the inflation objective, and argued that the statement should more clearly indicate that the Committee’s policy decisions were based on expected future inflation.

Bullard felt he needed to dissent on the revised language:

Although Mr. Bullard supported the statement without the changes and agreed that the Committee’s inflation goal is symmetric, he dissented because he judged that the amended language was not sufficiently focused on expected future deviations of inflation from the 2 percent objective. In addition, because the Committee’s past behavior had demonstrated the emphasis it places on expected future inflation, Mr. Bullard viewed the amended language as potentially confusing to the public.

Bullard’s concerns about inflation outcomes versus inflation forecasts now look prescient. Looking at inflation outcomes, the Fed has not met its inflation target in a symmetric fashion; outcomes have tended to fall on the low side of the Fed’s inflation target. This of course has not gone unnoticed. In late 2017,for example, Chicago Federal Reserve President Charles Evans said:

Indeed, actual inflation outcomes in the U.S. have been far from symmetric. As I noted earlier, core PCE inflation has come close to 2 percent only a couple of times since the recession ended in mid-2009, and these periods were far too short to be consistent with symmetry. This performance could easily be confused with a purposeful strategy in which 2 percent is a ceiling.

More recently, Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren said this about the outcomes:

In hindsight, it appears that the 2 percent inflation goal has essentially acted more like a ceiling, rather than a symmetric target around which inflation fluctuates. If the target were symmetric, we would expect to see a more balanced distribution, with a roughly equal number of observations above and below 2 percent. This frequency distribution and its skewing below 2 percent illustrates one of the key reasons to hold interest rates steady at present, as members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) await stronger evidence that we can consistently and symmetrically attain a 2 percent symmetric inflation target, a goal that has clearly been elusive over the past 20 years.

The addition of symmetry with respect to the Fed’s inflation target did not lessen concerns that 2 percent was a ceiling because the outcomes continued to suggest that 2 percent was a ceiling. Moreover, I think the focus on outcomes rather than the forecast has led observers both within and outside the Fed to conclude that the Fed has not effectively met its symmetric inflation target. Evans and Rosengren above both think they outcomes are not consistent with the symmetry. Nor does Powell, at least as of the December 2019 press conference:

BINYAMIN APPELBAUM. Binya Appelbaum, the New York Times. You’re about to undershoot your inflation target for the seventh straight year. Your new forecasts say that you’re going to undershoot it for the eighth straight year. Should we interpret the dot plot as suggesting that some members of your Committee believe that policy should be in a restrictive range by the end of next year? If so, can you help us to understand why people would be advocating restrictive monetary policy at a time of persistent inflation undershoots?

CHAIRMAN POWELL. Well, we—as a Committee, we do not desire inflation undershoots. And you’re right, inflation has continued to surprise to the downside—not by a lot, though. I think we’re very close to 2 percent, and, you know, we do believe it’s a symmetric goal for us. Inflation is symmetric around 2 percent, and that’s how we’re going to look at it. We’re not trying to be under 2 percent. We’re trying to be symmetrically around 2 percent. And I don’t—you know, I’ve never said that I feel like we’ve achieved that goal yet. The only way to achieve inflation symmetrically around 2 percent is to have inflation symmetrically around

2 percent, and we’ve been close to that but we haven’t gotten there yet, and we have not declared victory on that. So that remains to be accomplished.

And I don’t feel that we have kind of convincingly achieved our 2 percent mandate in a symmetrical way. Now, what do we mean by “symmetrical”? What we really mean is that we would look at—we know that inflation will move around on both sides of the target, and what we say is that we would be equally concerned with inflation persistently above as persistently below the target.

This exchange is fairly revealing. Powell believes that the Fed has not hit convincingly hit its mandate because inflation outcomes have not been symmetrical around 2 percent. But then he shifts gears and interprets the symmetric objective not about past outcomes, but instead about policy reactions (equally concerned) which hinge on the inflation forecast (inflation persistently above as persistently below). So which is it? Outcomes or forecast?

This is an important distinction because a symmetric objective with regards to the inflation forecast does not necessarily imply that the actual outcomes will be symmetric around the target yet some Fed officials, including Powell appear to believe that the persistently low inflation implies they are not meeting their objective. This in turn leads to a great deal of confusion. If they all agree they have not met the objective, then why hasn’t policy shifted accordingly? Shouldn’t the Fed be pursuing a more dovish strategy?

A Symmetric Target Does Not Necessarily Imply Symmetric Outcomes

I think the predominant view of Fed officials and market participants is that given the Fed’s stated symmetric inflation target, the actual inflation outcomes should be symmetric around the target. Yet it seems to be that this outcome is almost really a special case. If inflation was at 2 percent and future shocks were distributed equally around 2 percent, and the Fed responded equally to those shocks such that inflation would return to 2 percent, then the actual future outcomes would be symmetric around 2 percent.

But what if the starting point was below the 2 percent target, as was the case when the Fed formalized the inflation target? In that case, the path of inflation would approach target from below, and the shocks to inflation would be equally distributed above and below that path. If the Fed did not attempt to overshoot the target, as is the case in the inflation targeting framework and was the intention described by Yellen even after the addition of symmetry, the resulting outcomes would be distributed below 2 percent. To be sure, the distribution would approach 2 percent over time. Moreover, presumably after reaching 2 percent then future outcomes will be symmetric. Still, you need to get to 2 percent first. We should have realized that if the Fed was approaching the target from below, the actual outcomes would likely be below target for a possibly long time.

Hence, the fact that the inflation outcomes have not yet been distributed symmetrically around 2 percent does not necessarily mean the Fed has not adequately pursued their stated policy. They meet this objective if they consistently followed a systematic policy with regards to the inflation forecast, which means that they adjust policy in a symmetric fashion as the forecast changes.

Under the current framework, the Fed would not be pursuing their strategy if they did not react to inflation above target as they have reacted to inflation below target. The lack of above target inflation, however, has made it difficult to prove that this is the case. Still, Fed officials have said they would react symmetrically if inflation was above target. Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard recently said:

Of course, it is not entirely clear how to move underlying trend inflation smoothly to our target on a sustained basis in the presence of a very flat Phillips curve. One possibility we might refer to as “opportunistic reflation” would be to take advantage of a modest increase in actual inflation to demonstrate to the public our commitment to our inflation goal on a symmetric basis.For example, suppose that an unexpected increase in core import price inflation drove overall inflation modestly above 2 percent for a couple of years. The Federal Reserve could use that opportunity to communicate that a mild overshooting of inflation is consistent with our goals and to align policy with that statement. Such an approach could help demonstrate to the public that the Committee is serious about achieving its 2 percent inflation objective on a sustained basis.

Brainard is suggesting that a persistent overshoot is consistent with the symmetric inflation target. If a shock were to push inflation above 2 percent, it is reasonable to believe that the future outcomes of inflation would be symmetric above 2 percent as inflation returns to 2 percent from above. The Fed would thus be meeting its objective yet inflation in that instance would be persistently above 2 percent. Unfortunately, the Fed has not yet had an opportunity to prove that this is how they would in fact behave.

It thus appears that outside of the special case where inflation starts at 2 percent and is subsequently subject to symmetric shocks, the Fed is unlikely to experience symmetric outcomes even if they are pursuing their symmetric inflation objectives. To achieve symmetric outcomes regularly, they would need to define the relevant time horizon and be willing to engineer compensating overshoots and undershoots relative to the target. In other words, something along the lines of my recent suggestion:

The Federal Open Market Committee reaffirms its symmetric inflation target of 2%. In practice, the FOMC believes that it will have met its target if over the past five years the distribution of inflation outcomes is evenly distributed around 2%. Operationally, if the distribution of outcomes during the past two and a half years falls below 2%, the FOMC will adopt a policy stance intended to generate offsetting inflation outcomes over the next two and a half years to achieve its 2% target. The normal range of inflation outcomes is expected to be 1.5-2.5%.

This though is effectively a price level target, not an inflation target. In other words, if they want outcomes that are symmetric around 2 percent, they need a fundamentally different policy strategy.

From this perspective, Fed officials create a substantial amount of confusion when they emphasize they are not meeting their symmetric inflation target in a convincing fashion. I think they lack a policy framework to actually produce that outcome in any convincing fashion. If they want that outcome, they need a different policy framework. Until then, they shouldn’t complain about the outcomes because it suggests they are willing to make policy that is not consistent with their current framework.

Lack of Symmetric Outcomes a Potential Policy Error

The persistent undershooting of inflation that I think is a consequence of the Fed’s symmetric policy when inflation begins from below target is creating not just a communications challenge but also possibly a more substantial economic challenge. The Fed believes that sustained deviations from the inflation target will eventually impact inflation expectations. Moreover, some believe this is already the case. For example, back to Evans:

Why might inflation expectations have drifted down? The FOMC’s 2 percent inflation target is a symmetric one—that is, the Committee is concerned about inflation running either persistently above or persistently below 2 percent. One concern I have is that the public instead thinks the Fed views 2 percent as a ceiling that it aims to keep inflation under.

There is no single highly reliable measure of that underlying trend or the closely associated notion of longer-run inflation expectations. Nonetheless, a variety of measures suggest underlying trend inflation may currently be lower than it was before the crisis, contributing to the ongoing shortfall of inflation from our objective.

GREG ROBB. I just wanted to press a little bit about, what is the story the Committee— you know, when you get in the discussion today and yesterday about inflation, what kind of is the story that emerges?

CHAIR POWELL. So there are a bunch of different stories. There’s no real easy answer. One of them is just that the natural rate of unemployment is lower than people think. That’s one way to think about it, that there’s still more slack in the economy. Another is that expectations play a very—inflation expectations play a very key role in our framework and other frameworks, and, you know, there is the possibility that some people discuss of expectations being anchored but below 2 percent. And so, either way, inflation itself has kind of bounced around a little below 2 percent…

If persistently low inflation is eroding inflation expectations, re-anchoring those expectations at 2 probably will be difficult if the Fed’s framework is likely to yield persistently below 2 percent inflation when approaching the inflation target from below. The Fed needs an overshooting outcome to stabilize inflation expectations, but such an outcome is not possible within the current framework. Instead they seem to be waiting for a positive shock of significant size and persistence to prove they have a symmetric objective.

This creates another communications challenge. When Fed officials lament about the possible of falling inflation expectations, they imply a willingness to change policy accordingly. But they don’t have a policy strategy that allows for such change. The existing policy strategy is met as long as the inflation forecast anticipates achieving 2 percent inflation over the medium term. Remember, the Fed can’t have a forecast above 2 percent in the medium term because that implies deliberate overshooting that is not possible within the Fed’s current framework.

Conclusions

The proper interpretation of the Fed’s inflation symmetric inflation target is that it refers to the Fed’s reaction to inflation deviations. The Fed’s reaction function is the same for equal deviations above and below target. Policy will be set to achieve 2% inflation from above or below in an identical timeframe. This does not mean that the actual outcomes will be symmetric around 2 percent. The distribution of outcomes will depend on the timeframe and the whether the Fed is starting from below or above target.

The fact that we have not experienced symmetric outcomes around 2 percent, however, has been a great source of angst and confusion even if the framework was not designed to guarantee such outcomes. To guarantee such outcomes, the Fed would need to define the time horizon and actively seek inflation overshoots or undershoots as needed. Neither element currently exists and hence symmetric outcomes are likely special case and the lack of such outcomes does not by itself prove the Fed is not pursuing it inflation target in a symmetric fashion.

From a communications standpoint, the Fed should clean up its inflation story by acknowledging that in the absence of deliberate overshooting, the current framework may be successfully implemented and yet the outcomes are not symmetric. To be successfully implemented, the Fed needs only to symmetrically react to deviations from target. The lack of above target outcomes leaves them unable to prove that they are reacting in a symmetric fashion.

Currently, some Fed officials lament the failure of inflation outcomes to be symmetric around target. This in turn raises expectations that the Fed will change policy to yield different outcomes. But such a policy change would not be consistent within the Fed’s interpretation of its symmetric policy objectives. Bullard early on recognized the potential for this problem.

There is reason to believe, however, that the current framework does not exclude the persistent deviations from target than may destabilize inflation expectations. If this is a concern, then the Fed will need to move toward a price level targeting framework. Such a framework, however, requires deliberate overshooting and undershooting. It is not clear the Fed is ready to accept such a policy shift.

In short, either the Fed needs to improve its inflation story to be consistent with the policy framework or change the policy framework to match the inflation story. If inflation expectations are in fact still anchored at 2 percent, they probably should continue to emphasize the inflation forecast while deemphasizing the fact that inflation outcomes are not symmetric. Indeed, they should acknowledge that depending on the timeframe and starting point, the outcomes are not likely to be symmetric. This would help keep the inflation story consistent with the policy framework. Alternatively, if inflation expectations are slipping, they need to revise the policy framework accordingly.

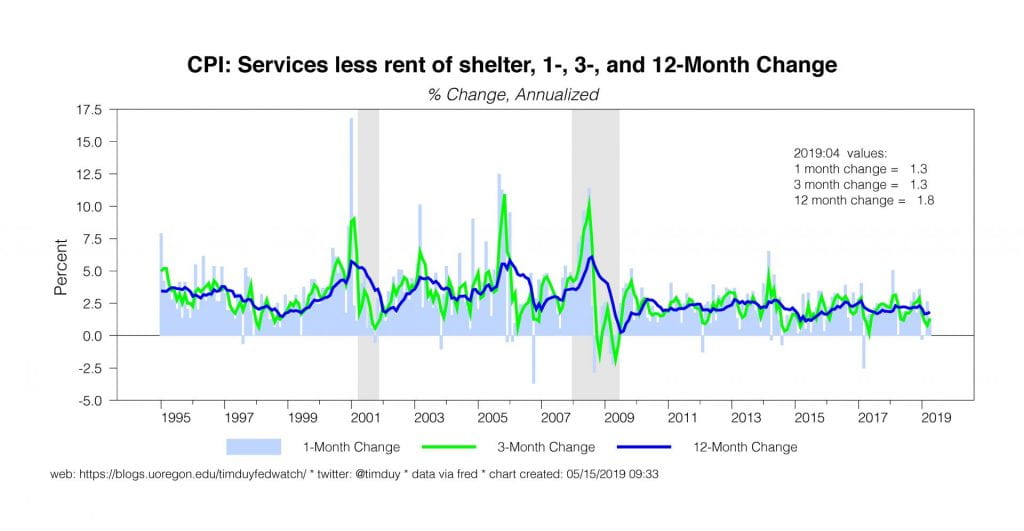

Used cars (not unrelated obviously to the overall weakness in the auto sector) and apparel helped drive the declines. The Fed believes the recent weakness of inflation is temporary and as such is resistant to cutting rates without a compelling story on the growth side of the equation. Continued weakness in the inflation numbers into the back half of the year, however, would lower the bar to a rate cut.

Used cars (not unrelated obviously to the overall weakness in the auto sector) and apparel helped drive the declines. The Fed believes the recent weakness of inflation is temporary and as such is resistant to cutting rates without a compelling story on the growth side of the equation. Continued weakness in the inflation numbers into the back half of the year, however, would lower the bar to a rate cut.