The US economy hit it out of the park in October. Rapid economic growth continues to fuel a labor market that delivers the enviable combination of job growth, labor force growth, and now faster wage growth. So far, this also continues in a low inflation environment. The Fed, however, doesn’t believe that situation will continue forever in the absence of tighter monetary policy. Expect the rate hikes to continue. Furthermore, I think you can make an argument that the labor market is close to the point where inflationary pressures will intensify. Something that everyone seems to think can’t happen anymore.

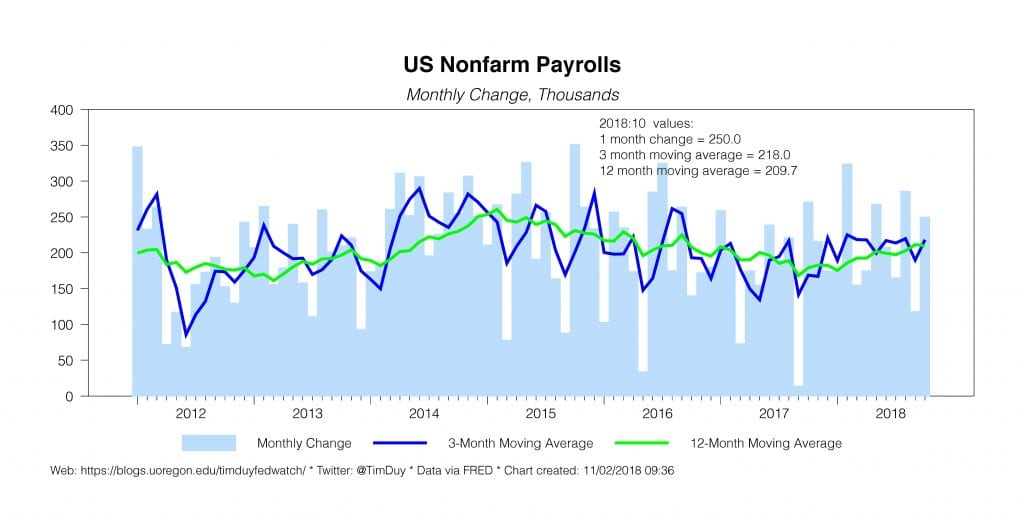

Nonfarm payrolls rose 250k, a solid above-consensus pace of job growth. Both the three- and twelve-month moving averages are above 200k. Fairly impressive growth for an expansion that is over nine years old. The pace still exceeds the Fed’s estimate of sustainable growth after the cyclical forces driving labor force growth give way to demographics.

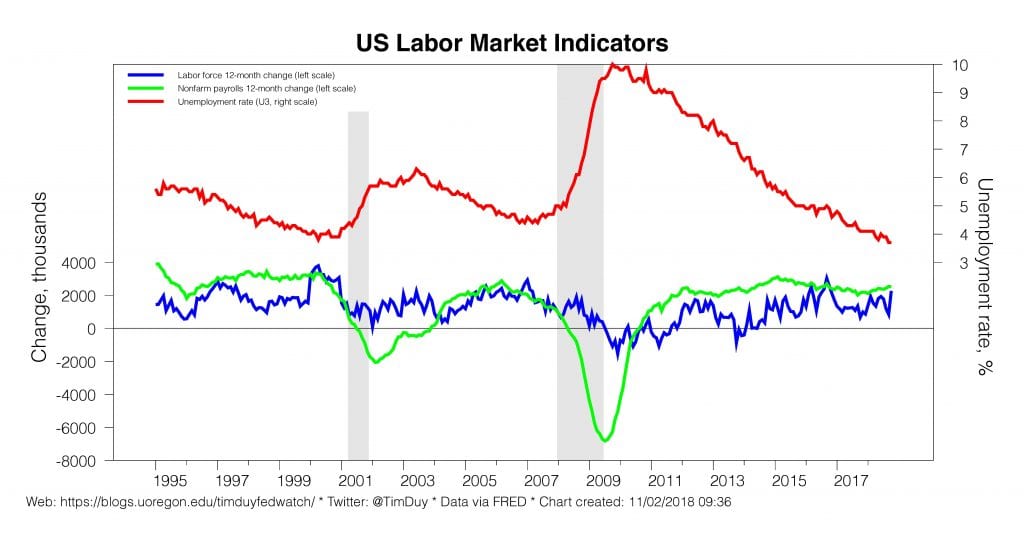

That day, however, is not yet at hand. Labor force participation ticked up, which helped hold the unemployment rate at 3.7%. Remember, the Fed anticipates this rate to hold through the end of the year, a bet that looks better this month than last. At least in the near-term, central bankers are labor force optimists.

The labor market does not look likely to sputter anytime soon either. The leading indicator of temporary help employment maintains steady growth, and we all know that initial unemployment claims are not sending out any warnings.

Wages grew 3.1% over the past year; over the past three months, the pace of gains has been 3.4% annualized. It would seem that wage growth appears to be kicking in, albeit at a low unemployment rate than the previous expansion.

In contrast, real wage growth has been trending sideways around 1% since the unemployment rate hit roughly 5.5%. This number is fairly consistent with productivity growth. Recall Federal Reserve Vice Chair Richard Clarida:

A sustained rise in inflation-adjusted, or “real,” wages at or above the pace of productivity growth is typical in an economy operating in the vicinity of full employment, and we are starting to see some evidence of this. I certainly hope it continues. Now, some might see a rise in wages as leading to upside inflationary pressures, but here, again, the experience of earlier cycles is instructive. In the past two U.S. expansions, gains in real wages in excess of productivity growth were not accompanied by a material rise in price inflation.

Of course, this time may be different, and as with growth, the job market could perform better or worse than the baseline outlook. However, for now, the increase in wages has been broadly consistent with the pickup in productivity growth that I have just discussed, and a rise in the still-low rate of labor force participation among the prime-age population provides scope for the job market to strengthen further without generating inflationary pressures.

Over the past year, nominal wage growth has been creeping up in tandem with underlying inflation to hold real wage growth around 1%. In other words, I think you can make an argument that we are at or beyond full employment with enough pressure on the economy that we see both faster wage growth and faster inflation. In other words, what I am seeing is that the world pretty much works out as you might expect.

If nominal wage growth continues to rise, the increase will need to be felt somewhere in the data – either faster inflation, faster productivity, or tighter profit margins. This is the space to watch. Obviously, the worst-case scenario is higher inflation, the best is higher productivity growth, and tighter profits margins fall somewhere in between depending on who you are in the economy.

I don’t know yet how this will play out. What I do know is that central bankers are very comfortable with the flat Phillips Curve story, almost complacent. Essentially, they have been surprised so many times by how low they can push unemployment that they don’t really trust their ability to estimate the natural rate of unemployment and are now defaulting to a dovish scenario that allows them to maintain a gradual pace of rate hikes despite fairly hot growth. There don’t appear to be many skeptics left among central bankers. My experience is that when everyone believes the same story, it’s time to get a new story.

Bottom Line: Jobs data gives no reason for the Fed to think their job is done; rate hikes will continue.