Another rich example of indigenous cultural survival (even if showing influences from European traditions over time) can be found in Mesoamerican musical forms. We will use this page to assemble materials that may be useful to music teachers or to those who might not teach music per se, but who might wish to enhance a language or a literature class with elements of ethnomusicology.

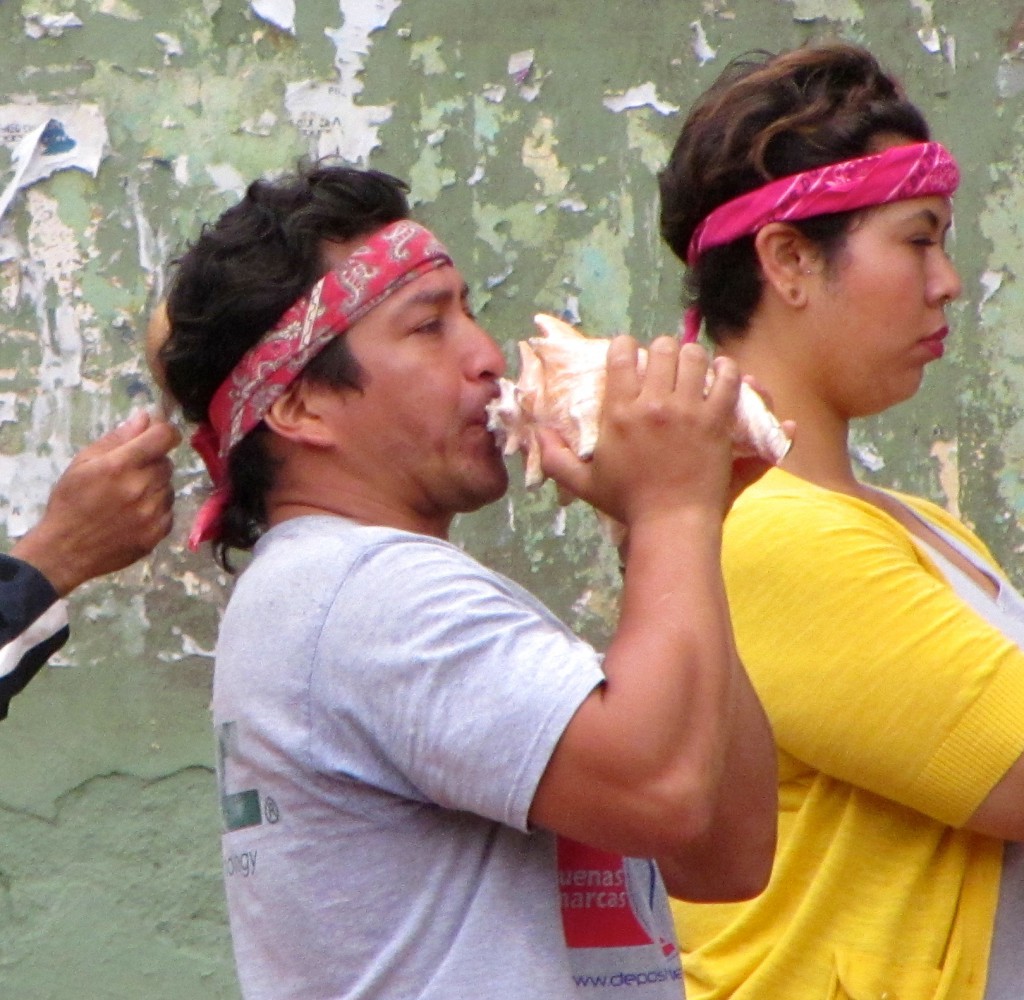

Below is a photograph taken in Oaxaca on 3 July 2014 of a local man blowing a conch. He was taking part in some type of religious revival ceremony where a small group had incense and other objects, and they were bowing to the four cardinal directions, consciously trying to connect with pre-Hispanic ways.

The Nahua teponaztli was log that was hollowed out from underneath and then cut with an H-shaped opening. The two projecting tongues of the H were struck with rubber-tipped sticks. The image above is an old teponaztli similar to many found in Mexican communities until recent times.

Murals

Murals in the Maya zone include images of huge trumpets, the subject of an illustrated study by Roberto Velázquez Cabrera, published on line in Spanish, “Hom-Tahs de Bonampak.”

Museum Artifacts

- Museo Rufino Tamayo, Morelos #503, has in its collections some artifacts that could be helpful for a study of indigenous musical traditions.

- The historical museum at the Santo Domingo Cultural Center also has some items that could be photographed for use in a study of indigenous music.

Classic-era flute from Veracruz with a double pipe and female and male figurines sitting on top. Museo Rufino Tamayo. (S. Wood, 2010)

The decorated conch shown above, from Monte Albán, Classic Period, has carvings showing priests presenting an offering of a human cranium on an altar, an image of the deity of rain, a person blowing a conch, a representation of the surface of the earth (monster-like), and the head of a serpent (also associated with the earth’s surface).

The teponaztli shown above has, on its ends, figures (such as this eagle) that appear to have song emerging from their mouths. Museum of Natural History, New York. (R. Haskett, 2012)

A singing jaguar(?) carved onto the end of a teponaztli. Museum of Natural History, New York. (R. Haskett, 2012)

The Nahuas had no stringed instruments until they were introduced into Mexico by Europeans. Melodies came largely from flutes and whistles, and percussion came from drums (teponaztli and huehuetl, the latter a standing drum struck with the hands) and rattles. Bones (sometimes human bones) were also notched to serve as raspers.

Nahua Songs

Pre-Columbian Nahua songs, at least as they survived a century after European contact, retain a distinctly indigenous flavor even as they also refer to the Spanish invasion and seizure of power and incorporate Christian religious influences. For a free, online English translation of Nahuatl-language songs by John Carl, visit FAMSI’s site, “The Flower Songs of Nezahualcoyotl: Ancient Nahuatl (Aztec) Poetry.” This material may or may not have been sung in what is now the state of Oaxaca, but we do know that Nahuas settled in Oaxaca.

Colonial and Nineteenth-Century Music

Music and dance forms in New Spain (colonial Mexico) frequently preserved — and reinvented — indigenous themes. In the image above, from Joaquín Antonio de Basarás y Garaygorta, Origen, costumbres, y estado presente de mexicanos y philipinos (1763), lam. 3, 118, we see the Dance of the Emperor Moctezuma. Note the band playing on both the right and left, and the use of headdresses and feather adornments.

Music and dance regularly accompanied theatrical performances, which is the subject of a wonderful online essay by Diana Taylor, “Scenes of Cognition: Performance and Conquest,” with wonderful illustrations.

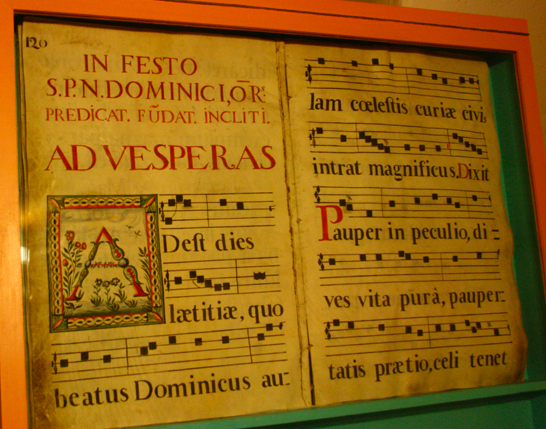

In 2009, on display in Oaxaca, were dozens of recently discovered sheets of music spanning a three-hundred year period. Some trunks (baúles) with this music inside were discovered in San Bartolo Yautepec, much to the delight of ethnomusicologists studying the evolution of musical forms in Oaxaca over the centuries. For an article (in Spanish) and photos, see: http://www.iohio.org/esp/fest2009.htm.

Poster about the demonstration of music from the trunks of sheet music discovered in Yautepec. (S. Wood, 2009)

Early Twentieth-Century Photographs

Musicians in some Oaxacan community ca. 1930s or 1940s. Photographer unknown. Slides in WHP collections.

“Pedro es el maestro que sabe…,” a villancico; Archivo de la Arquidiócesis de Oaxaca (Photo, R. Haskett, Oaxaca, 2011)

Free Concerts Today

Orquesta Pasatono is a Oaxacan ensemble (below) that plays a fusion of Mixtec and European musical traditions. They have given our former NEH Summer Scholars musical demonstrations. This year we may simply attend one of their public performances on the stage just south of Santo Domingo, the Pañuelo, which is assembled for special fiestas in the open air. Concerts are free.

Susan Harp is a local Oaxacan singer who includes songs in Otomí, Nahuatl, Mixtec, and Zapotec as a part of her repertoire.

The marimba was introduced from Africa to the Americas in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. According to Wikipedia, “traditional marimba bands are especially popular in Guatemala where they are the national symbol of culture, but are also strongly established in the Mexican states of Chiapas, Tabasco, and Oaxaca.”

European musical influences continue in Oaxaca. The Basque restaurant, El Asador del Vasco, on the southwest corner of the zócalo, has a band of musicians who come to entertain in their interpretation of the Basque style of Spain.

A restaurant on the pedestrian street, Macedonio Alcalá, called the Hostería Alcalá, sometimes has performers in the evening who conjure up a very old European or Spanish colonial flavor.

Street Musicians

A high percentage of street musicians are indigenous men (though not all are male) who are playing accordions, which is an instrument brought to Mesoamerica by the Europeans.

Oaxacan Artistry Today

Mare Advertencia Lirika

Mare Advertencia Lirika is a rap artist from Oaxaca. In the following linked videos taken by Vinny Civarelli Jr., she gives an introduction on the emigration of rap music into Mexican culture. Her beginnings start with interests in graffiti art in and rap music soon after. Mare uses rap music to create an social identity that she could not find within her culture. Her lyrics are socially conscious and aware of the political events around her. She was featured in a documentary, Cuando Una Mujer Avanza (When a Woman Steps Forward) by Simon Sedillo.

Articles

- Mexicolore’s discussion of How Music Came to the World, a book about the divine origin of music among the Aztecs.

- Mexicolore’s report about a concert in 2009 at the British Museum, “Music at the Royal Courts of Spain and Mexico“

- Mexicolore’s brief exploration of the association of animals with musical instruments

- A free, full-text PDF with multiple authors, Music Archaeology: Mesoamerica, is a special issue of the journal The World of Music 49:2 (2007), with articles emphasizing Maya and Aztec musical artifacts and information drawn from manuscripts: http://www.mixcoacalli.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/both_wom2007-2.pdf

-

“A Visual Research Experience: The Ceremonial Songs of Concheros,” is a full text essay in Spanish with illustrations about conch blowers in weather-related dances and songs in modern-day central Mexico.Gonzalo Sánchez S. is one of the authors in the World of Music special issue above, but he has also published some full-text essays about ancient Oaxacan musical traditions (with images) in Academia.edu, such as: “Sounds of Death and Life in Mesoamerica: The Bone Flutes of Ancient Oaxaca” and “Los_artefactos_sonoros_del_Oaxaca_Prehispanico.“

- John A. Donahue, “Applying Experimental Archaeology to Ethnomusicology: Recreating an Ancient Maya Friction Drum through Various Lines of Evidence,” full-text study published by FAMSI.

- Cameron Hideo Bourg, “Ancient Maya Music Now with Sound,” M.A. Thesis (with images): http://etd.lsu.edu/docs/available/etd-11162005-171011/unrestricted/Bourg_thesis.pdf

- “Misteriosa música prehispánica,” http://www.puntodincontro.com.mx/articoli/cultura06072013-sp.htm (with an image of a teponaztli, Aztec drum)

- “Ofrecerán charla sobre las características de la música prehispánica,” http://www.elporvenir.com.mx/notas.asp?nota_id=680025 (with an image of turkey-shaped? flutes)

- “Estudian polifonía en la música prehispánica,” http://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/2013/06/26/906075 (with six images)

- Spanish-language wikipedia site about the Mixtec ethnomusicologists and orchestra, Pasatono, of Oaxaca, whom we may get to hear in a free, open-air concert during the Guelaguetza celebrations in July: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pasatono

- Wikipedia Site, Maya Music (with images): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_music

- Flawed, but still interesting site at Berkeley about Maya music: http://oldweb.geog.berkeley.edu/ProjectsResources/MayanAtlas/MayaAtlas/instrument.htm

Audio-Visuals

- Mexicolore’s page on Aztec music includes a video of a demonstration of the teponaztli wooden drum and the conch shell; the page also contains images from codices and many wonderful links relating to ethnomusicology of Mesoamerica

- Christopher García is an acclaimed musician who specializes in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican musical instruments and forms: http://christophergarciamusic.weebly.com/index.html

- Rey Ortega playing re-creations of various types of Maya flutes: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cWjOaZFXo3s

- Steve Turre playing a shell as part of a jazz ensemble: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cRTXJHzL3s8&list=PLbH4KrFkeYTH6bWHaMRDX707mY7R8Scoy

- Tommy Adolfsson, a conch player in Sweden: https://myspace.com/tommyadolfsson

- Jim Berenholtz, performing ethnomusicologist with a specialization in Mesoamerica, provides from free sound clips on his website (scroll down a ways): http://www.jimberenholtz.com/em/xo4.html

- John Burkhalter, ethnomusicologist with Mesoamerican expertise, offers images, links, and video clips on this website: http://tlacatecco.com/tag/mesoamerica/

- “History and Evolution of Latin Prehispanic Music,” a website with interesting images

- Video of a lecture by Vanessa Rodens, “Sonidos del pasado: investigaciones sobre la música maya,” hosted by the Universidad Francisco Marroquín, Guatemala, from 2008 (1 hour and 2 minutes)

Additional Resources

Please see our pages on Dance and the Guelaguetza.