Foxes

Foxes (kitsune 狐) are another of the most famous and best-loved of yōkai. From time immemorial they’ve been credited with shape-shifting abilities and the power to bewitch or even possess humans, which makes them feared as yōkai. But their status as servants of the Shintō harvest god Inari also makes them objects of reverence. Their association with Inari helps explain why they’re one of the most common motifs in senjafuda; this connection is explored in depth on the page about collectors and foxes. This page, meanwhile, will concentrate on more overtly yōkai-esque depictions of foxes.

This includes the two slips above. The first (also discussed in connection with yōkai and parades) depicts a fox wedding procession, or kitsune no yomeiri 狐の嫁入り. Early modern weddings included a procession escorting the bride from her parents’ house to her new husband’s house, ceremonially demonstrating how a bride was thought to be leaving her old family behind and joining her new one. Children’s stories extended this practice to other creatures, with stories of mouse weddings and monster weddings featuring the same kind of procession. Foxes, too, were thought to have wedding processions, but given their magical nature their ceremonies were attended by eery signs: rain from a clear sky. This unusual but real phenomenon is still called “a fox wedding procession.” In the first slip above the procession is depicted at the bottom of a two-chō slip, in delicate sketchwork. The bride is in a palanquin being carried on poles in the center of the parade of attendants. More attendants at the back of the train carry a chest containing her trousseau, while attendants in the front carry large paper lanterns.

The second slip also shows a fox parade, or rather the front end of it. We can see the lantern bearers, assorted attendants, and at the right edge of the slip a palanquin with a foxy face peeking out through the window. The procession is cutting behind a shrine gate, which frames the name of the business being advertised by this slip: the Unohi-za, a small theater that stood in the Shukuin-chō area of the city of Sakai, south of Osaka. Note that this slip, while found among the Starr senjafuda, does not have the chō outlines visible in the background that a multi-chō senjafuda normally would (compare with the first slip). It may in fact simply be a flyer for this theater.

Trickster Foxes

The five slips below highlight two aspects of the fox as magical being. One is its proclivity for enchanting humans for their own amusement. The other is its connection with Inari worship. Often when foxes are depicted in their capacity as messengers of the god, their mischievous nature is downplayed, but not here. In each case these foxes are playing their tricks on or very near shrine grounds. And in fact the stated theme of the 1927 series from which the first four come is: “Famous Inari Festivals of Edo and People Being Bewitched by Foxes.” In the senjafuda imagination, at least, there’s no distinction between godly foxes and trickster foxes.

The first slip celebrates the Toyokawa Inari shrine in Akasaka, Tokyo (the name of the shrine in each slip is written on the banner on the left side of the scene). It shows a man playing a game with three foxes. The two foxes on either side of the man, holding a rope with a loop in it, are dressed as women, suggesting the man thinks he’s amusing himself with geisha. The fox in the center, in its animal form, has one paw raised in a gesture echoed by the man’s hands, suggesting that this fox is the puppeteer.

The second slip celebrates the Gōriki Inari shrine. Here a pair of men have stripped to their loincloths and are about to face each other in sumo wrestling. The fox in the background with the fan is the referee about to start the match, and two more foxes are sitting “ringside,” ready to enjoy the match. This shrine seems to have been associated with feats of strength; it boasts a large stone said to have been lifted in a demonstration of strength by Sannomiya Unosuke, a famous early 19th century strongman. This may explain why the foxes here have selected sumo for their entertainment.

The third slip celebrates the Hikan Inari shrine in Asakusa. Here too one of the foxes seems to be orchestrating the action with raised paws. Another is seated on the back of a man who has clearly been convinced he’s a horse. His friend marches next to him like a samurai’s attendant, but he’s holding an Inari shrine banner instead of a spear.

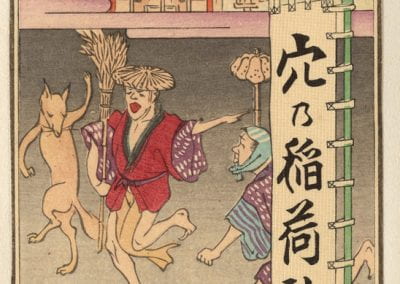

The fourth slip celebrates the Ana no Inari or “Burrow Inari” shrine, so called because it was built over a fox burrow; today the shrine is known as the Hanazono Inari. The fox at left has bewitched two peasants into thinking that they’re samurai retainers on parade. The one on the left is holding his broom like a spear, while the other man has placed a kabocha atop a pole in imitation of the decorative finials used in processions. The loose loincloth is an appropriately comic touch, showing just how deluded the men are.

The fifth slip is unrelated to the first four but similarly shows foxes working mischief in full view of a shrine gate. Here foxes have enchanted two senjafuda pasters into thinking they’re having their hair dressed by professional barbers. The slip is discussed in further detail on the “Collectors and foxes” page.

In each case, what’s worth noting is how harmless these foxes’ pranks are. Some foxes of legend use their powers in more vicious ways, but these foxes are hurting nothing more than their victims’ dignity. It’s all in good fun, at least in these slips.

Foxes in Kabuki

The first two slips below show magical foxes in the more dramatic form that’s typical of their appearances in kabuki plays, where their shape-shifting abilities are utilized to add an air of the uncanny to gloriously melodramatic plots.

The first slip has to do with one of the best-known fox stories in Japan, that of Genkurō the fox. It’s told in the classic 1747 play Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees (Yoshitsune senbonzakura 義経千本桜). The play follows medieval warrior-hero Yoshitsune as he flees to safety when his brother, the shogun Yoritomo, seeks to destroy him. Yoshitsune sends away his mistress, the dancer Shizuka, and asks one of his retainers, Tadanobu, to watch after her; Yoshitsune gives Shizuka a drum as a keepsake. Yoshitsune eventually finds temporary refuge in Hiraizumi, where Shizuka catches up with him, Tadanobu still watching over her. Then another Tadanobu shows up, and it’s revealed that the Tadanobu following Shizuka was in fact a shape-shifting fox. In a famous series of transformations between human, humanoid fox, and fox forms, the fox Tadanobu tells how long ago his parents were caught and their pelts used to make the drum that Yoshitsune gave to Shizuka. The fox has been seeking the drum ever since, out of loyalty to his parents. Touched by his filial piety, Yoshitsune gives the fox the drum, and also gives the fox one of his own names: Genkurō. The fox Genkurō rejoices and promises to watch over Yoshitsune in battle forever after. The play’s combination of heart-tugging filial piety narrative and unnerving yōkai effects have made it a favorite of audiences since the 18th century.

This slip is sponsored by a rakugo performer, Kokontei Shinba, and it’s called kitsunebi 狐火, or fox-fire, the mystic flames that are seen dancing in the air near foxes when they’re at their most yōkai-esque. In stage presentations of the Genkurō story, the robes worn by the actor playing the fox are decorated with kitsunebi, much like the robe worn here. This slip appears to depict the dancer Shizuka, instead of the fox, but she’s wearing the fox-actor’s robe and her right hand is held in a position meant to suggest a fox’s paw. She’s holding a warrior’s helmet, a reference to a scene in the play where the fox Tadanobu sets up a suit of armor by a tree and Shizuka places the drum on top for a head, then dances before it as if it were her master.

The second slip is part of a series in which each slip presents two smaller images, each approximately of a size and shape to suggest matchbox labels, against the distinctively striped curtain used on the kabuki stage. Here the lower image is of a kabuki actor, while the upper image shows a fox surrounded by kitsunebi. The writing on the upper image identifies the actor and the role: Ichikawa Ichizō 市川市蔵 in the role of Ogasawara Haito in the play The Ogasawara Disturbance (Ogasawara sōdō 小笠原騒動). In the play, Haito saves a fox, who later comes back to protect Haito.

The third slip above depicts a kabuki play that has nothing to do with foxes. The play is the famed Wait a Moment! (Shibaraku 暫), a showcase for the actors in the hereditary Ichikawa Danjūrō line. The costume, with its oversized sleeves emblazoned with the actor’s family crest three concentric squares, is particularly famous. This slip shows a fox taking the place of the actor; in fact it’s a paper fox puppet of the type discussed on the “Collecting and appreciating” page. As such it doesn’t relate to a stage depiction of a shape-shifting fox, but rather approaches the intersection of senjafuda, kabuki, and fox beliefs from a different angle.

Fox Priests

The votive slip below relates to a shape-shifting fox popularized not in kabuki but in kyōgen, a comic theater tradition dating back to the medieval period. The fox is known as Hakuzōsu and features in a play called Fox-Catching (Tsurigitsune 釣狐). The play centers on a man who traps foxes. A shape-shifting fox assumes the form of the man’s uncle, a priest called Hakuzōsu. In this guise he tries to put a stop to the trapper’s activities by scaring him with tales of fox yōkai. But when it sees the deep-fried rat the trapper has been using as bait for his traps, the fox can’t help himself: he takes the bait (an excerpt from this passage in the play can be viewed here). In this way the play, like most kyōgen, moves through a series of comic reversals between hunter and priest/fox, ending in a stalemate (the fox manages to escape from the trap).

The slip below is part of a series called “Shadows of the Stage” that shows scenes from plays in silhouette—the viewer is being challenged to recognize the play and the scene from a mere shadow on a screen (this series is also discussed on the “Cats” page). This slip shows the fox from Fox-Catching in profile, wearing a monk’s robes and hood and carrying a walking stick, but in an intermediate stage of transformation revealing its true nature as a fox.

The motif of a fox in priestly garb was taken up by artists in other media, too. The next two images above also show Hakuzōsu, but in three-dimensional form. They’re netsuke 根付, a form of personal accessory once common in Japan. Early modern clothing didn’t have pockets in the same way modern trousers and shirts do. Instead, one often placed small personal items such as the ubiquitous pipe and tobacco in small pouches with cords attached; the cords were then passed through one’s sash, so the pouch would hang suspended. A toggle was attached to the end of the cords to catch on the sash and keep the item from falling. These toggles, netsuke, developed into highly sought after miniature carvings in wood, ivory, coral, or other material. And just like senjafuda (another miniature art form), many netsuke drew on popular stories for their artistic motifs.

The first netsuke above shows Hakuzōsu in much the same way as in the senjafuda: fox-faced, but in humanoid form wearing priestly robes and hood and leaning on a staff. Here the fox is facing downward—perhaps gazing hungrily at a deep-fried rat? The second netsuke shows the same subject, but with an ingenious twist—the face actually rotates. On one side (shown in the photo) is a human priest’s face, and on the other is a fox’s muzzle. The carver has cunningly created a netsuke that, like its fox subject, can shape-shift.

The fourth item above is also a netsuke, and at first glance it too may seem to depict Hakuzōsu, but a closer examination reveals something else. This is a man in a fox mask, and what appears to be a priestly hood is a rain-hood made of straw. Whether this relates to another story or is simply a playful image is unclear. But it, like the other two netsuke, suggest an even more personal connection with yōkai than in senjafuda. As articles of attire (in theory, at least) these netsuke would have been something a possessor used and handled on a daily basis, and thus an opportunity for self-expression on a very personal level, like a keychain or smartphone case for a modern person. The appearance of yōkai in netsuke further attests to their centrality in early modern culture (and in modern representations of early modern culture).