Collectors and foxes

Foxes are easily the most common yōkai in the Starr collection of senjafuda, but they do not always appear in their yōkai form.

Foxes in Japanese folklore and popular culture have three main aspects. One is as normal animals; the occasional golden or reddish fox seen in senjafuda may be acknowledgments of this. Another is as shape-shifting magical foxes; these are the classic foxes or kitsune of yōkai stories. The third is as servants of the god Inari, protector of agriculture and harvests. Like shape-shifting foxes, Inari-servant foxes are usually depicted as white, and are often accompanied by balls of flame or other indications of supernatural potency. Stone statues of foxes are usually found in front of Inari shrines, and Inari ema often feature illustrations of foxes.

It is in this capacity as Inari’s familiars that foxes most frequently appear in senjafuda. This seems to be an acknowledgment, as well as a survival, of senjafuda’s historical roots in Inari worship. Inari was a particularly popular god among the commoners of Edo, with small shrines in many neighborhoods of the city. One popular form of worship was the senjamairi 千社参り or “thousand shrine pilgrimage,” a visit to as many Inari shrines as one could find. Sekioka Senrei argues that this practice became so intertwined with early votive-slip pasting that the name of the one came to be used for the other: thus senjafuda, or “thousand-shrine slips.”

Originally, then, harifuda may have been most frequently used in pilgrimages to Inari shrines. In a classic example of early modern self-reflexivity, a frequent motif in kōkanfuda is Inari worship. We see shrine buildings, shrine gates, and most of all Inari foxes. Sometimes these are in the (relatively) realistic form of the familiar stone statues of foxes that one would find at a shrine. Sometimes they are in the doubly self-reflexive form of Inari foxes depicted on Inari shrine ema (in turn depicted on senjafuda). And sometimes they are in the form of live foxes leaping or flying about in ways that suggest god-derived power. It is these last that remind us of the close connection, or lack of any clear distinction, between yōkai foxes and divine foxes. The same iconography of dancing flames and white fur that marks an Inari fox is used in stage productions to signify shape-shifting foxes (as in the play Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees).

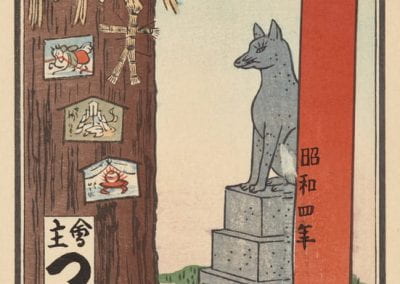

The first slip above depicts a stone fox statue next to the gate to an Inari shrine. The tree in the left foreground has a straw rope with white paper strips hanging from it to indicate that it’s a sacred tree. Three ema are hanging from the tree, as is a straw doll. The doll adds a spooky touch, since it was believed that one could curse somebody by nailing a straw doll representing them to a sacred tree at midnight. The shrine gate has a senjafuda pasted to it that says “first slip,” indicating that this is the first image in a series. The bottom of the gate has “graffiti” that gives the date: 1929.

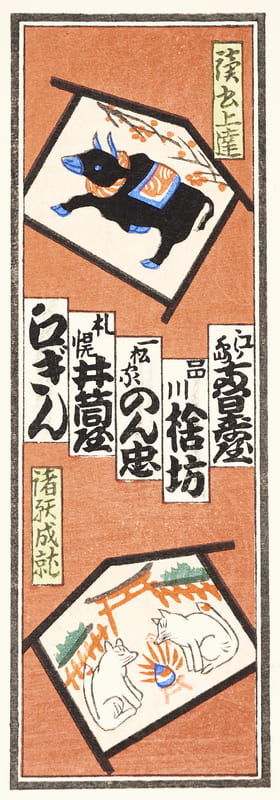

The second slip above comes from a series depicting ema. The ema are labeled with the particular blessing they are meant to request, rather than the name of the shrine they belong to (which a viewer was presumably meant to recognize). The top ema in this slip shows two divine foxes flying near the top of a shrine gate surrounded by red and blue wish-fulfilling jewels; it promises answers to “all requests.” The bottom ema shows a fox next to rice plants, with a wish-fulfilling jewel over its back; promises a “bountiful harvest.”

The third slip belongs to the same series. The bottom ema shows two foxes seated in front of a shrine gate. Between them is a flaming wish-fulfilling jewel. The ema is labeled “fulfillment of all requests.”

The fourth slip is also from the ema series. The bottom ema shows two foxes with a flaming wish-fulfilling jewel between them. The ema promises “exorcism of fox possession.”

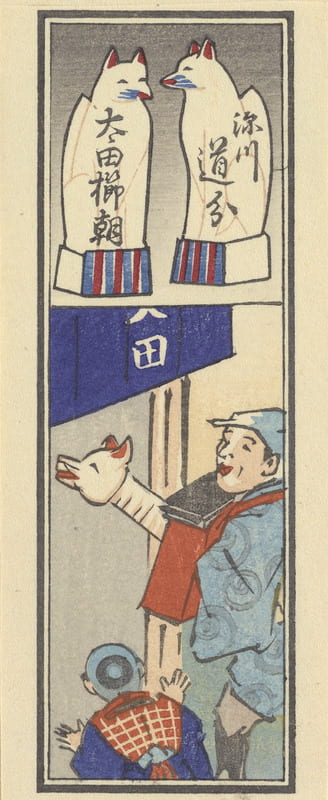

The images below are perfect examples of the use of foxes in senjafuda in an Inari context. They’re selections from a large set of one-panel slips depicting different Inari shrines. At the top of each slip is a pair of shrine foxes; the distinctive blue and red stripes on the base mark these as clay figurines (Imado-yaki 今戸焼) sold to worshipers. One of these bears the name of the shrine being referenced, and the other the daimei of a senjafuda practitioner; an unusual feature of this design is that the daimei are presented in the same calligraphic style as the shrine name, rather than in the distinctive senjafuda calligraphy usually used. This creates a pleasing symmetry and thematic equivalence between shrine and worshiper. Beneath these is an illustration connected in some way with the shrine. Not all of the illustrations feature foxes, and the ones that do use them in a variety of ways, all depending on the viewer’s knowledge of the shrine and the lore connected with it.

From left to right:

The slip for the Sankō Inari in Ningyō-chō shows a pair of anthropomorphized cats, a mother and child, no doubt in reference to this shrine’s reputation for helping worshipers find lost housecats.

The slip for the Chōei Inari in Ikegami shows a divine fox appearing on a cloud to the medieval Buddhist cleric Nichiren; the shrine is connected to the headquarters of Nichiren’s sect, the Ikegami Honmonji, and the Chōei Inari is considered Nichiren’s protector.

The slip for the Michiwake Inari in Fukagawa shows a street entertainer amusing a child with a fox puppet.

The slip for the Tamahime Inari in Asakusa shows a fox dressed up as a princess (Tamahime means “jewel princess”).

Other reminders of the close connection between yōkai foxes and Inari foxes can be seen in the two images below.

Above is a scene of two men who have been taken in by foxes who are pretending to be hairdressers. The man on the right is gritting his teeth while the fox-barber pulls his topknot tight. The man on the left is admiring the fox-barber’s handiwork by holding mirrors in front of his face and behind his head—or so he thinks. The “mirror” behind his head is actually an ema that reads Ryōgoku, an Edo neighborhood. The box and brush in the bottom right corner identify these men as senjafuda enthusiasts on a pasting excursion, probably to one of the Inari shrines in the neighborhood—one of their slips can be seen on the crosspiece of the shrine gate in the background. Perhaps to get back at the men for their impudence, the shrine’s fox guardians have bewitched them.

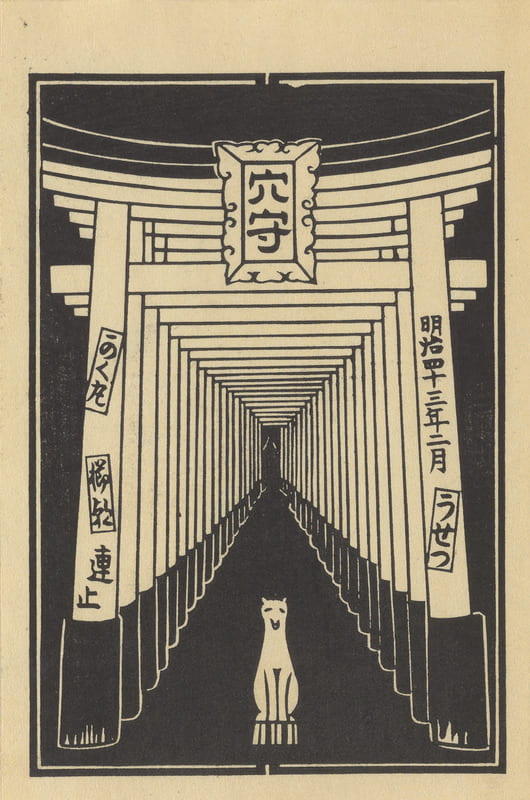

The scene above shows a stone fox statue in front of a series of shrine gates belonging to the Anamori Inari in Tokyo. The placement of the statue is unexpected, since typically such statues are found in pairs flanking the gate, not blocking the worshiper’s way like this. The fox’s inscrutable stare combines with the monochrome design of the print to lend an air of otherworldliness to an otherwise ordinary encounter.