Tattoos in print

Just as senjafuda collecting circles overlapped with circles of collectors of other materials (such as matchbox labels), senjafuda-based social networks often overlapped with other kinds of organizations. We’ve noted elsewhere the close relationship between senjafuda collectors and supporters of the Kanda Shrine Festival. On this page we look at the intersection of senjafuda culture with a very different kind of group: tattoo lovers.

Most visitors to this site will no doubt have heard of the Japanese practice of full-body tattooing: gloriously detailed images of gods, heroes, or monsters surrounded by waves, cherry blossoms, or other background designs that can extend over as much of the body as the individual likes. Complete coverage of back, buttocks, thighs, arms, and chest is not rare among people sporting such tattoos, and they can often involve several colors, although blue (or bluish-black) and red are usually prominent in color schemes.

While tattooing in various forms goes back into antiquity in Japan, the tattoos we’re talking about are a phenomenon that really begins in the 19th century—curiously, right around the time that senjafuda were becoming an object of exchange and collecting. And, like senjafuda, they owe a great deal to woodblock-print culture. The practice was in fact inspired by characters in the Ming-era Chinese vernacular novel Shuihu zhuan (in Japanese, Suikoden), or The Water Margin, which had been the focus of growing scholarly and popular interest throughout the 18th century in Japan. In the early 19th century, it was translated into accessible Japanese, igniting a popular vogue for Water Margin-alia in prints, plays, and other kinds of adaptations. Several of the book’s heroes are described as having large decorative tattoos on their backs, which gave the illustrator of the translation, Katsushika Hokusai, the chance to come up with dashing tattoo designs for the page. But it was Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 in the 1820s who really brought the full-body tattoo into fashion with a full-color print series of Suikoden heroes, many of whom (in his rendition) sported precisely the kind of blueish full-body tattoos that we now associate with Japan. In other words, Japanese tattooing as we know it was inspired by the illustrations in the translation of a Chinese book.[1]

Like any art form, tattoos were meant to be displayed, and were most sought by men who could display them: men whose jobs involved manual labor, and who therefore might legitimately work half-naked in hot weather. It was a plebeian art form, in other words—much like senjafuda. And just as senjafuda survived into the modern era among people most invested in preserving and reviving the past, tattooing also came to be imbued with a sense of tradition and nostalgia. This made it a perfect motif for senjafuda. And since yōkai were a perfect motif for tattoos…

Above are two slips from a series spotlighting arm tattoos. The album in which these are found has eight such slips; whether this represents the complete series is unknown. The first slip above shows a tattoo of a hannya mask with the striped prop often used by noh actors using this mask . The second slip shows a thunder god on his cloud (for more on both these motifs see the page on oni). The combination of fierce (yet elegantly rendered) tattoo and knotty arm muscles nicely conveys the appeal of tattooing.

Note that aside from the tattoos themselves and the daimei in the green square top left, the slips are identical. This is the case with all the slips in this series (well, in some the kimono is blue with a white pattern rather than white with a blue pattern—but the pattern itself is identical; incidentally that pattern is the logo of the senjafuda group that made these slips). The result effectively suggests how a tattoo can express an individual’s personality, making him stand out in a crowd.

In addition to the daimei, each slip in this series bears another legend: “To Ōkame.” This was a senjafuda collector who was also a tattoo enthusiast, a member of a group called the Chōyūkai 彫勇会 or “Tattooed Braves Association.” This group was founded in 1902 by a group of people sporting tattoos by the same master tattooer; they met regularly to show off their tattoos and celebrate tattoo culture. There seems to have been significant overlap in membership between the senjafuda collectives and the tattoo fans, as the slips below show.

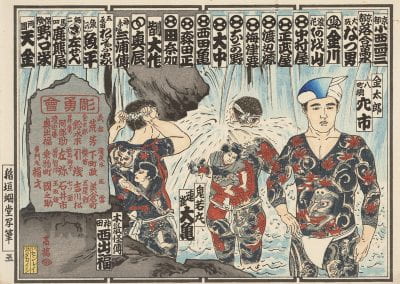

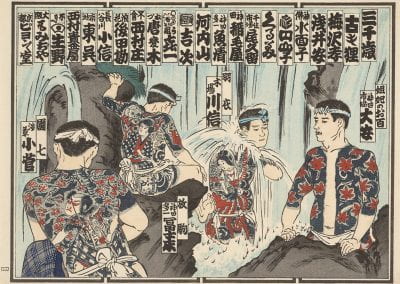

The two slips above are from another series involving Ōkame. This one is dated August, 1916, and shows tattooed men bathing at a waterfall—both a traditional ascetic practice and a great opportunity to display their tattoos. This is part of a longer series showing eighteen men in a panoramic view of the pool; all are in the Starr collection. The set is reproduced and annotated in Miyamoto Tsuneichi’s Senjafuda.[2] They include a typically ferocious assortment of motifs; note the hannya mask motif again.

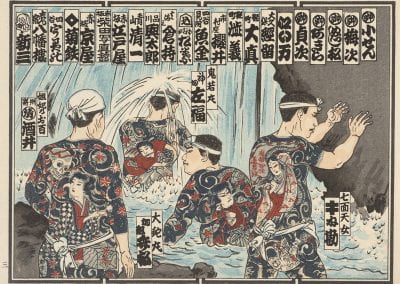

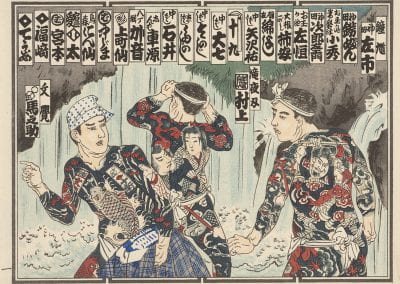

The slips above are from a set commemorating a later outing of the Chōyūkai, this one in 1925, to Ōyama. Among the motifs can be seen an assortment of demon and tengu masks, a mitsume (three-eyed monster), Shōki quelling a demon, skulls come to life, and a monster cat, among other strange and wonderful scenes. Is this a collection of yōkai? Is it a collection of tattoos? Is it a collection of senjafuda? Is it self-expression on the part of the tattoo artist, the men undergoing his needle, the senjafuda artist, or the collectors commissioning the slips—and how many of the men are playing multiple roles in this exchange? This series is a brilliant evocation of the interplay of social networks, collecting, nostalgia, amusement, riddling, print culture, and occasional eros at work in senjafuda.

This series is further discussed on this Kanda local history blog (Japanese only), which notes that Frederick Starr knew members of the Chōyūkai through his senjafuda activities. In 1932, at his request, he was invited to one of their gatherings, where he was able to observe dozens of tattooed men in the flesh.