Yōkai, individually

In the “Yōkai, collectively” section we explore ways in which yōkai are presented en masse, in large arrays that hint at a wide and crowded world of supernatural creatures. The idea there is to convey a sense of the variety of yōkai found in the early modern imagination as represented in senjafuda and other artifacts of woodblock-print culture. Along the way we explore some of the overarching concepts scholars have used to make sense of yōkai, in particular Michael Dylan Foster’s concepts of pandemonium and parade.

In this section, we focus on a select few yōkai that are well represented in the UO collection of senjafuda. The idea here is to get to know these creatures a little better while exploring the range of ways they’ve been used in senjafuda. Some of the yōkai best known to fans today appear in only one or two slips in the collection. By the same token fans might be surprised at which yōkai get the most attention from senjafuda collectors. A consideration of why this might be will help us to better understand the significance of yōkai in Japanese culture as a whole.

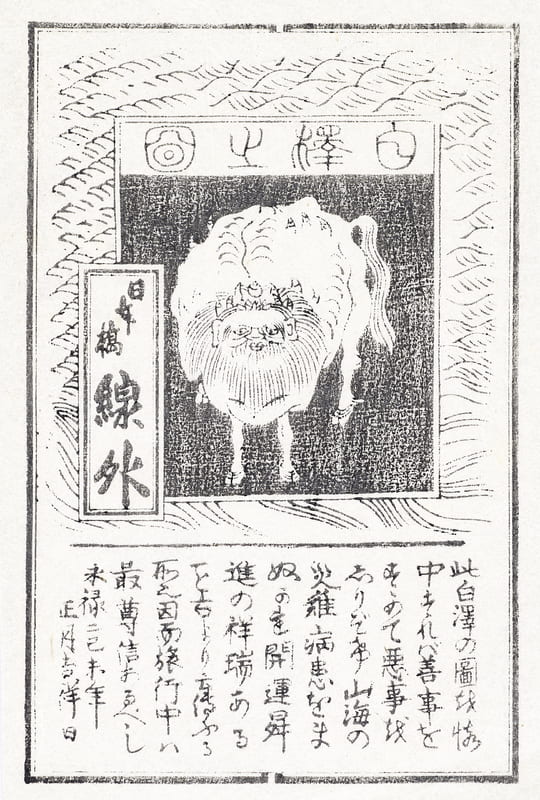

The slip above depicts a hakutaku 白澤 (Ch. baize) (“whitemarsh”). In Chinese tradition it’s one of several magical creatures that are thought to manifest themselves when a ruler’s reign is just. The hakutaku is envisioned as a horned creature with extra eyes on the side of its body; it can understand and speak the language of humans, and is sometimes depicted with a human face. In the Edo period printed amulets showing a hakutaku were sometimes carried to ward off danger. This slip reproduces one. The text beneath the image (dated 1559) is part of the original charm, and promises that whoever carries this picture of a hakutaku next to his or breast while striving to do good and shun evil will be preserved from all the calamities of mountain and sea, protected from illness, and guided to good fortune.

The original amulet is an example of how yōkai in early modern Japan could have significance beyond just entertainment—in this case, the hakutaku offers protection in exchange for faith. The senjafuda, in reproducing this amulet, is appealing to the antiquarian tastes of the modern collector, offering a piece of early modern religious culture. On another level, as a printed votive slip reproducing a printed amulet, this is woodblock-print culture in its latter days celebrating woodblock-print culture in its earliest days.