Tengu

Tengu have a very long history in the Japanese imagination of the supernatural. Like tsukumogami, they’re in some ways more closely associated with medieval tales, so they don’t always show up in early modern yōkai group portraits (note the absence of a tengu on the sugoroku board). But older tengu stories continued to be told, and tengu imagery was preserved in masks, ema, and other religious paraphernalia. And as discussed on the “Collectors and tengu” page, tengu played an important part in the senjafuda practitioner’s self-image, making them a frequent appearance in senjafuda. The beautiful but enigmatic slip above is a further example of that, showing a scroll containing (among other writing) the names of some senjafuda groups, partially contained in a wooden box marked “thousand shrine pilgrimage.” Bundles of simple daimei fuda meant for pasting are scattered around, and in the background is a small decorative tengu mask affixed to a wooden plaque, making it seem as if all the senjafuda activities represented by the various items are taking place under the tengu’s watchful eye.

More examples of the self-reflexive use of tengu in senjafuda are explored on the collectors and tengu page. This page will mostly concentrate on instances when tengu are being depicted for their own sake.

The slip above shows a tengu’s face (or the mask of one) on what’s identified as a charm against cholera (korori 虎狼痢) originating in Osaka. The tiny hat is part of the tengu’s garb as a yamabushi; the combination of priestly imagery and the tengu’s stern, forbidding visage no doubt made it a fitting image for banishing disease.

The word tengu is usually written with characters that mean “heaven’s hound” 天狗, and as Michael Dylan Foster notes,[1] ancient references to tengu did seem to connect them with dogs, but that association was soon lost. Medieval depictions of the tengu associated them with crows, and early modern depictions usually envisioned them as red-faced priestly men with long noses. Proverbially associated with the quality of arrogance, they can be mischievous or downright violent.

Tengu are almost always presented in the garb of a Buddhist priest, specifically a yamabushi 山伏 or “hider in mountains.” Yamabushi were familiar yet mysterious figures in the medieval and early modern religious landscape: they lived on mountains and engaged in ascetic practices reputed to give them magical powers. Despite their religious lifestyle they appear in stories as social outsiders, figures of mischief or outright menace, characteristics shared by tengu. In popular stories and plays tengu came to be conflated with yamabushi, as each was thought capable of transforming into the other.[2]

The relationship between tengu and Buddhism goes far deeper than appearance. The defining characteristic of tengu in medieval legends is their opposition to Buddhism. Haruko Wakabayashi explains that tengu “were identified with ‘ma,’ the enemy of the Dharma or the temptations of passion and desire that hinder one from attaining ōjō [rebirth in the Pure Land].”[3] But in medieval narratives, what appears at first to be evil or inimical often later proves to be good, a manifestation of Buddha’s mercy, disguised, an expedient means to lead people toward salvation. In the case of tengu, antagonism to Buddhism is often transformed into a kind of perverse sponsorship of Buddhism. In the kind of paradox that medieval storytelling revels in, tengu are both threats to and protectors of Buddhism. They’re both priests and anti-priests.

Tengu and Mount Kurama

The tengu’s duality (or non-duality!) is perhaps best expressed in the legend of the tengu of Mt. Kurama, one of the most famous of all tengu stories. It emerged in the medieval period as an outgrowth of the story of Minamoto no Yoshitsune, a twelfth century warrior who helped his brother Yoritomo defeat the Taira warrior federation and establish their own Minamoto as the supreme power in the land. After Yoritomo established himself as shogun he turned on Yoshitsune, leading to events chronicled in plays such as Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees (discussed in relation to shape-shifting foxes elsewhere on this site).

Tengu enter Yoshitsune’s life when he’s a young boy. With the country under the domination of the Taira, Yoshitsune, as the scion of the rival Minamoto federation, is a potential threat. He’s sent to the monastery on Mt. Kurama to be raised by priests, but while there he knows only persecution from the young Taira boys who are his fellow acolytes. And despite his piety, young Yoshitsune is more cut out to be a warrior than a monk: he takes to practicing martial skills alone in remote mountain vales near the temple. In some versions of the story these vales are merely spooky, but in many versions they’re described as the abode of tengu, who take the boy under their wing and train him in the martial arts. His future success as a warrior, then, is in many legends credited to supernatural aid.

The most influential presentation of the Yoshitsune-tengu legend is the 15th century noh play Kurama tengu 鞍馬天狗. The play begins with the boy Yoshitsune, ostracized by the other acolytes, encountering a mysterious yamabushi, himself shunned by the priests on the mountain. The boy is kind to the yamabushi, and this human connection leads the yamabushi to reveal himself as the Great Tengu of Mt. Kurama, and to take Yoshitsune under his protection. The Great Tengu sends servant tengu (called “leaf tengu” or konoha tengu 木葉天狗) to begin Yoshitsune’s training, and then finally trains the boy himself, promising him protection and aid ever after. By the end the tengu is revealed to be firmly on the side of good (Yoshitsune is in every way a hero)—but the play never lets us forget that tengu are also threatening, monstrous figures who “live in enmity of men,” as the play puts it.

The magnificent triptych above is a depiction of the Yoshitsune-tengu encounter as legends imagine it happening. Entitled “Yoshitsune on Mount Kurama,” it’s by Utagawa Yoshikazu, the same artist who created the yōkai sugoroku board discussed elsewhere. In the right panel we see the Great Tengu of Mount Kurama (here called Kurama Sōjōbō, after Bishop’s Vale, the spot on the mountain where the play has him first encounter Yoshitsune): he’s the white-haired mountain of a man seated in front. He’s given human features, but his left hand, covered by his red robe, makes for a shape suspiciously reminiscent of the long red nose seen in other depictions of tengu (such as the senjafuda at the top of this page). The Great Tengu is surrounded by other named tengu (the play lists several tengu who fly here from other holy mountains all over the country); two are presented in more crow-like guise, while one is shown in human form. In the center panel we see the boy Yoshitsune (here identified by his boyhood name of Ushiwakamaru) sparring with several unnamed leaf tengu. The leaf tengu are depicted as having the wings and beaks of ravens (but with monstrous teeth in their beaks). Yoshitsune, who seems to have already learned to fly from the tengu, is besting them easily. In the left panel, looking on admiringly, are three warriors who will come to serve or aid Yoshitsune in various capacities (and figure in various stories and plays). From left they’re Kijirō Sachitane, Hitachibō Kaizon, and Kisanta Seietsu.

The diptych above shows the same encounter as it appears on the noh stage. At left is the Great Tengu, and at right is the boy Yoshitsune. Yoshitsune is played by a child actor wielding a halberd (naginata) instead of the sword shown in the triptych. The tengu is played by a mature actor in a mask and red wig. The mask is of the variety known as a beshimi 癋見, and it shows a grimacing, bearded face that’s close to human but meant to suggest a god or demon. This, rather than the long-nosed mask familiar from later eras, is what is used on the noh stage for tengu. The actor also hold a fan made of feathers, an accessory also found in depictions of Daoist wizards and understood to be a magical item allowing flight and other feats. The print is by artist Tsukioka Kōgyo 月岡耕漁 (1869-1927), known for several series of prints that, like this one, depict noh actors in costume acting out scenes from plays. His prints combine a documentary approach, paying close attention to details of costuming and posture, with a subtle sense of stylization—here the figures seem to be floating in a grayish-blue void, drawing the viewer’s attention to the vibrant color of their robes and the tension of their confrontation. The Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art holds around seventy noh prints by Kōgyo; two more are discussed on the “Oni” page.

The three senjafuda above all relate to the Kurama legend in some way. The first depicts a tengu as presented on the noh stage, most likely from the play Kurama tengu. The intentionally muted colors of this slip show a sense of restraint appropriate to a noh-related slip, and if anything only serve to elevate the impact of the costume, mask, and feather fan.

The second shows two crow-beaked tengu facing off in a sparring match. The slip, from the late Edo period, seems to be incomplete. A heavily muscled red arm extends into the frame from the right, holding a fan in the manner of a referee; presumably the scene continues to the right to reveal the identity of the referee (the Great Tengu? another yōkai?), but this is all we have. The referee’s fan suggests an improvised sumo match during an outing to enjoy cherry blossoms (note the petals wafting gently through the scene); the play Kurama tengu is set during cherry blossom season. This slip was designed by ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Yoshitsuya 歌川芳艶 (1822-66).

The third slip shows what appears to be the figures set atop a Kanda Shrine Festival float. Here the boy Yoshitsune balances on the Great Tengu’s forearm. Note that Yoshitsune is armed with a fan rather than a sword or halberd here, and that while the tengu’s costume and fan resemble that used on the noh stage, his nose is long and his face is red, unlike the beshimi mask. For more discussion of slips showing the Kanda Festival floats, see the page on “Yōkai, collectively.”

Tengu Masks

As noted above, tengu were often depicted with crow-like beaks and wings, and just as often with human features. On the noh stage they were depicted as supernatural beings, but with fairly human-looking faces. However, during the early modern period it became standard to depict tengu with red faces and long noses, and masks of this design became standard parts of popular religious observance. Long-nosed tengu masks are by far the most frequent way in which tengu appear in senjafuda. This is to say that while some senjafuda depict tengu themselves, far more depict tengu masks, or festival floats or other mock-ups utilizing tengu masks (and some of these are meant to depict the god Sarutahiko, who has come to be represented with a tengu mask, rather than tengu per se).

The first slip above is a classic view of the standard tengu mask as mask: red, long nose, bushy white facial hair. The strap by which the mask would be attached to the wearer’s head is visible, suggesting it’s ready to be donned and used, perhaps in a festival setting. The mask sits atop a drum and a ceremonial spear stands in the background; both would also be used in a festival parade or dance. Interestingly, the artist’s signature on this slip is the same as on the slip showing the tengu from the noh stage above.

The second slip is part of a series showing ema (discussed further on the origins and offerings page); the ema here shows two tengu masks, one in the crow design and the other of the long-red-nose type.

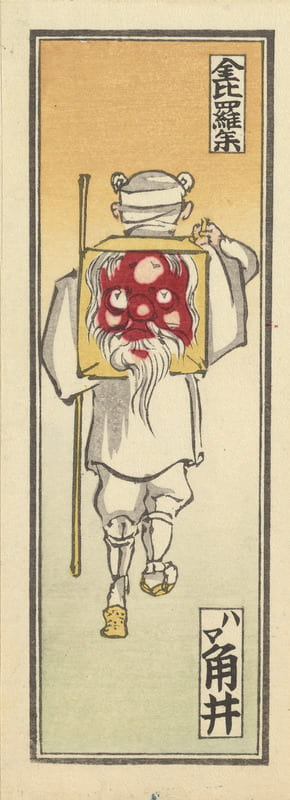

The third and fourth slips show one particular use of the long-nosed tengu mask. Here oversized masks are mounted on frames and worn as backpacks. The white clothing on the people carrying these curious items marks them as pilgrims; in fact, pilgrims to the Konpira Shrine on Shikoku customarily carried such backpacks on their way to the shrine. The sight of white-clad pilgrims walking away while a tengu glares back at the viewer was immortalized in landscape printmaker Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重’s depiction of Numazu in his Fifty-Three Stages of the Tōkaidō series in the 1830s.

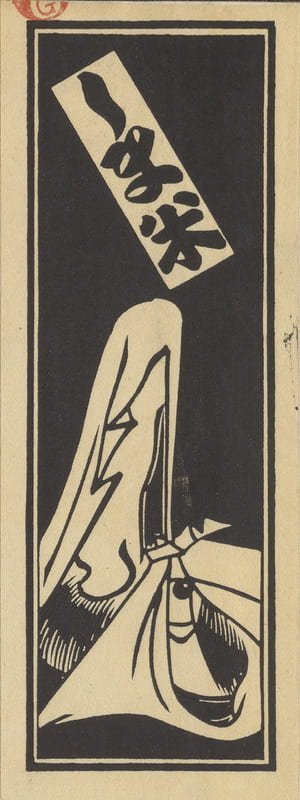

The fifth and sixth slips use the tengu mask for its obvious phallic properties. The fifth represents a failed attempt to wrap the mask in a cloth; the side of the nose and part of the beard can be glimpsed in a way that seems vaguely obscene. The sixth is even more graphic. It sets the tengu mask next to another familiar folk-art mask, one variously known as Okame, Ofuku, or Otafuku. Regardless of the name, this mask depicts a smiling, round-cheeked young woman and is used in various comic contexts. Here the slip is showing the two masks placed in such a way as to accidentally-on-purpose suggest sex.

For many more examples of the use of tengu in senjafuda, see the page on “Collectors and tengu.“

References

[1] Michael Dylan Foster, The Book of Yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015), pp. 130-39.

[2] See further discussion in Carolyn Anne Morley, Transformation, Miracles, and Mischief: The Mountain Priest Plays of Kyōgen (Cornell University East Asia Program, 1993).

[3] Haruko Wakabayashi, The Seven Tengu Scrolls: Evil and the Rhetoric of Legitimacy in Medieval Japanese Buddhism (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2012), p. 19.