Kappa

Kappa are among the best-known yōkai today, both in Japan and abroad—they’ve even made their way into the Harry Potter mythos. At least in modern Japan, they have a relatively stable and easily identifiable set of characteristics: they live in water, have shells on their backs, like cucumbers, and on top of their head is a dish filled with water. If the water spills out of the dish, they’re weakened. As Michael Dylan Foster notes, the early history of the kappa concept is complex, incorporating a variety of legends about aquatic creatures from all over Japan, but by the late Edo period we can see a relatively stable imagination of the kappa in prints and books.[1] The sugoroku gameboard discussed elsewhere is a good example. The Starr-related slip above is another.

Despite their popularity in both the early modern and modern periods, kappa are noticeably scarce in the University of Oregon’s senjafuda collection. The Starr Collection contains very few compared to other kinds of yōkai, and while (as we’ll see) the Shōbundō Collection contains more, they’re mostly postwar. Those parts of the Shōbundō Collection that overlap with the Starr Collection, period-wise, are similarly free of kappa. It’s not easy to know exactly why this is, but one possibility suggests itself if we take a closer look at the kappa on the sugoroku board.

The “Kappa of Bandō Tarō” is pretty much everything a modern yōkai fan might expect—with one important exception. And this exception is significant for understanding how in modern Japan yōkai have been transformed from figures of menace to (mostly) harmless cartoon character-like beings. The kappa on the sugoroku board is not harmless, if you look closely: in its right hand it’s holding a baby, and with its left hand it’s extracting that baby’s internal organs.

The popular Edo period image of kappa held that they were particularly interested in extracting a victim’s shirikodama 尻子玉 or “butt-ball,” a mysterious piece of human anatomy that is only heard of in connection with kappa (maybe it only exists so kappa can seek it). It may be that what the Kappa of Bandō Tarō is extracting is the shirikodama itself, although from the size and shape of the extraction it seems more likely to be a group of organs accessed after removing the shirikodama. While this proclivity of the kappa’s was such common knowledge in the early modern period that it was thought fit for a children’s game, it has passed quietly out of the mythology of modern kappa.

This may be simply because the image of a sharp-clawed water creature disemboweling its victim from below is too violent and grotesque for modern sensibilities. But there may be a second reason why this aspect of kappa has been deemphasized in modern Japan. In early modern Japan, kappa were metaphorically associated with male-male sexuality. In early modern Japan, sexual relations between males were in many cases recognized or even celebrated. But over the course of Japan’s “modernization” along Western lines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the West’s repressive attitude toward homosexuality came to be adopted in Japan, and sex between males came to be stigmatized.[2] Did this ultimately lead to a revision of how kappa came to be imagined? And do lingering associations with what was now deemed a socially unacceptable form of sexuality explain why there are so few in early 20th century senjafuda? After all, if anybody in the 1920s might be expected to know what kappa had once signified, it would be senjafuda collectors.

The first slip above appears in multiple copies in the Starr Collection, no doubt because it’s one representing Starr himself. It depicts a toothy and sharp-clawed kappa carrying a huge cucumber on its back. The two daimei at the top say “Starr” and “Gonzales” (Manuel Gonzales, Starr’s traveling companion), while the text above the kappa’s knee says “America.”

The second slip above is also connected with Starr; his name is one of three daimei “written on” the paper lanterns at bottom right. The other two names are Maebashi Han (short for Hanzan, Starr’s interpreter) and Setchō (Ōta Setchō, a calligrapher). The slip depicts, not a “real” kappa, but a man in a kappa costume, putting on a lively skit on what appears to be a festival stage. The kappa is being “caught” by Ebisu, one of the Seven Lucky Gods of Japanese popular belief; a god associated with fish and fisherman, Ebisu is often depicted in the act of catching a large fish. If Starr was notorious for his love of kappa (as his newspaper interview suggests), then this slip may be figuratively staging a kappa dance to welcome Starr to a senjafuda collectors’ meeting. Would it be going too far to imagine this is an image of Starr getting “hooked” on senjafuda?

The third slip, too, depicts not a “real” kappa but—probably—a fake one. The scene is a drinking party, and on the right a turtle (presumably not magical) has drawn eyes on a red lacquered dish and put the dish on its head to startle its drinking companions. Since “a turtle with a dish on its head” is a pretty good thumbnail description of a kappa, the slip may be inviting the viewer to see a visual pun on a kappa here. If the “kappa” on the right is a fake, its drinking companions are “real” yōkai, two shōjō 猩々. These are creatures ultimately derived from Chinese myth (Ch. xingxing), and are often depicted as red-haired boyish-faced creatures that understand human speech; they’re particularly fond of sake. Shōjō-turtle pairings are not unknown in late 19th century art; this one features a drinking party that has clearly gotten a bit out of hand. A label affixed to the album identifies the artist as Kawanabe Kyōsai, famous for his yōkai art and also a self-described shōjō (the term is also used sometimes to refer to a heavy drinker), but the signature doesn’t seem to be Kyōsai’s.

As noted above, kappa images are far more common in postwar senjafuda, as evidenced by the Shōbundō Collection. Below are four examples.

As Foster notes,[1] kappa illustrations have proliferated in postwar Japan due to a number of manga featuring kappa, and the kappa’s adoption as the mascot of a popular brand of sake. These uses have helped a (mostly) sanitized version of the kappa to regain its central place in the popular yōkai imagination. The slips above conform to this postwar vision of the kappa.

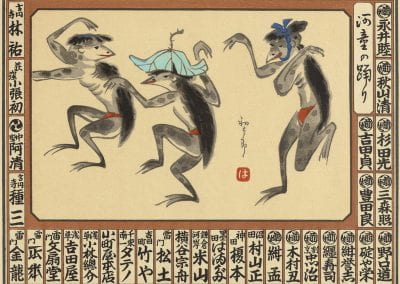

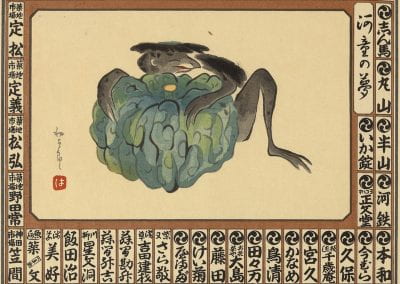

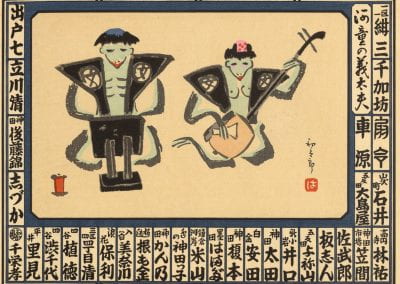

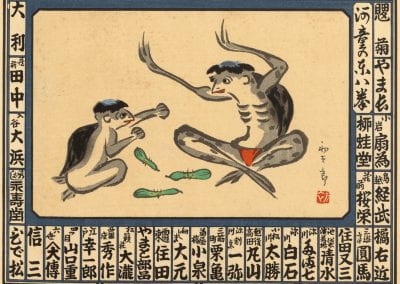

They’re from a set of six slips made in 1961 as “Six Views of the Kappa at Rest.” In the first image, “The Kappa’s Dance,” three kappa are dancing with abandon; one has a bandanna tied around his head, while another is wearing a lily pad as a hat. The red loincloths are a colorful (and modestly risqué) touch. In the second image, “The Kappa’s Dream,” a kappa is napping with his arms around a huge kabocha—dreaming it’s a gigantic cucumber, perhaps? In the third, “The Kappa Chanter,” an obviously female shamisen player accompanies a gidayū (dramatic) reciter. In “The Kappa’s Hand Game,” two kappa play a variant on rock-paper-scissors with cucumbers as the stakes. There may be a further yōkai reference here, as this version of the game, called “fox-fist,” involves a fox, a hunter, and a landowner as the three options. The hunter beats the fox (because he can shoot it), but loses to the landowner (because the landowner can lord it over the hunter). The landowner can lord it over the hunter, but can be enchanted by the fox.

As an imagination of the daily life of a yōkai, these senjafuda correspond nicely to the oni series discussed elsewhere on this site: the yōkai’s life is like ours, but maybe a little more carefree. As depictions of kappa they’re expertly drawn humorous sketches—and, let’s be honest, a little kitschy. As such, they’re perfect examples of modern kappa.

References

[1] Michael Dylan Foster, The Book of Yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015), pp. 157-67.

[2] Gregory M. Pflugfelder specifically discussed kappa imagery in 19th century Japan in Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600-1950 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 197.