The world of senjafuda

Senjafuda 千社札 literally means “thousand-shrine slip,” a term that refers to the phenomenon’s roots in religious pilgrimage. An alternate term used by scholars and collectors is nōsatsu 納札, “donation slip.” To understand what senjafuda are today requires understanding a little about what they used to be in the past.

Senjafuda were originally slips of paper that a pilgrim would paste on a temple or shrine wall or gate, a practice some people still follow today. Slips used for pasting are typically white with black writing that identifies the paster by a pseudonym—called a daimei 題名—and occasionally other elements (such as a house crest or shop logo). Originally senjafuda for pasting could be handwritten, but usually they were woodblock-printed. Senjafuda for pasting were made in a variety of sizes and shapes.

As senjafuda became collector’s items, made for exchange rather than pasting, the size was standardized at about 15 cm (5 in.) high by 5 cm (2 in.) wide. Slips made for exchange can feature complicated pictorial and/or design motifs rendered in full color, but they retain traces of their origins in pasting slips by including the daimei of the person or name of the group that sponsored or commissioned them. As works of art, therefore, senjafuda typically combine both pictorial and verbal elements, with the writing being an integral part of the overall composition.

Similarly, many senjafuda designs came to exceed the standard size, but they were always conceived of in terms of the standard single slip. When used as a unit of size, the slip is called a chō 丁. A single design may therefore occupy two, four, or even larger numbers of slips (i.e., 2 chō, 4 chō, etc.). The design may be formally interrupted by the borders of its individual component slips (meaning it can only be fully appreciated by setting several slips side by side), or it may be continuous, with the edges of the component slips being depicted as if sticking out from behind the design. Part of the fun of senjafuda is how they play with the restrictions imposed by their small size.

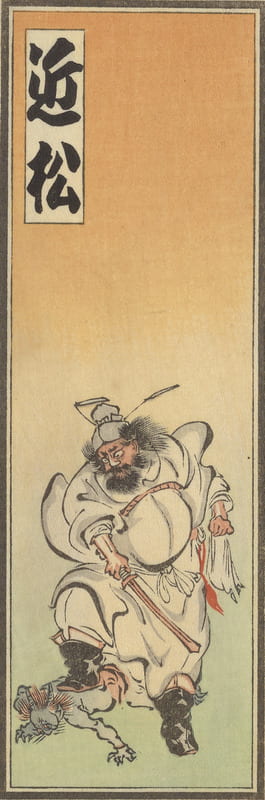

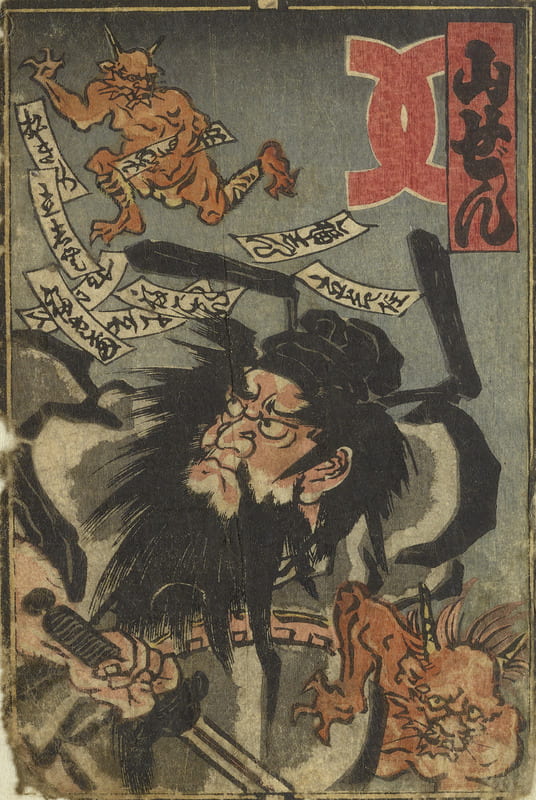

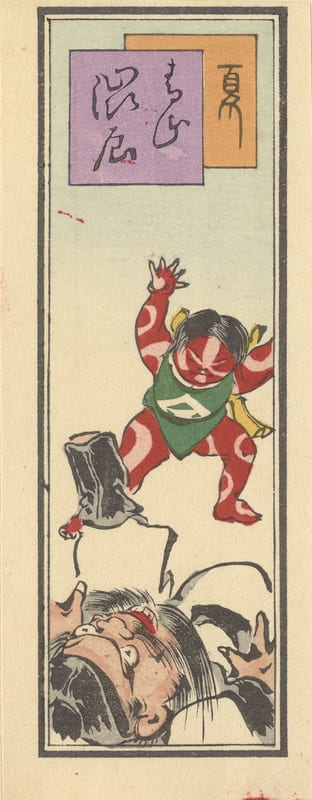

Below are three slips each depicting the same motif: Shōki (Zhong Kui in Chinese), a mythical queller of demons. From left, the first is a standard one-chō senjafuda depicting Shōki treading on an oni. The sponsor’s daimei (“Chikamatsu”) may be seen in a block on the top left. Next is a two-chō senjafuda showing Shōki wrestling one oni while another flees in the background; the sponsor’s daimei (“Yamazen”) may be seen in the top right. Note that the edges of the two component slips may be seen peeking out from behind the main design, an indication that this may be thought of as comprising two slips. Third is another two-chō senjafuda showing Shōki chasing away an oni; in this case the edges of the two component slips can also be seen in the center of the composition, dividing the background while Shōki and the oni leap across the frames, so to speak. The brushwork in the third slip is not quite as fine as in the second, but the way the figures cross between the component slips lends the composition a dynamic quality that the second one lacks.

Alternatively, a single slip may contain a self-contained design but be designed as part of a larger group or series of related motifs. This kind of senjafuda can be appreciated as individual works of art but also collectively, as ensembles. Both large multi-slip images and single-slip series are typically produced as group efforts, commissioned as the collective self-representation of a club of senjafuda aficionados. One of the fascinations of senjafuda is the glimpse they give us of social networking among the groups that commissioned, collected, and sometimes pasted senjafuda.

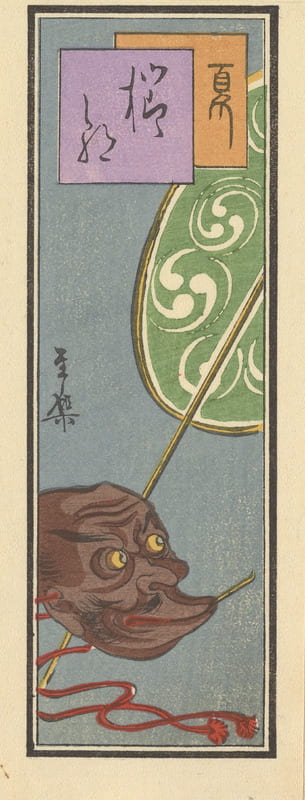

Below are three slips from a series of seasonal motifs. The purple square at the top of each slip contains the daimei in calligraphy; the orange square behind it identifies the season. The slip on the left (“summer”) shows Shōki being startled by Kintarō (a boy of legendary strength who figures in medieval folk tales). The one in the middle (“summer”) shows a large fan and a mask (possibly a beshimi mask from the noh theater, often used for monsters). The one on the right (“autumn”) shows another mask, a hannya or demoness from the noh theatrical tradition, with a striped cane often used as a prop by actors wearing this mask. Each slip may be appreciated on its own or collectively, as part of a playful representation of seasonal motifs (in which yōkai play only a small part).