Night parade of a hundred demons

Anecdotal accounts of demons and monsters parading through the streets of Kyoto at night can be found in sources as far back as the early 12th century, but the modern visual imagination of this phenomenon is generally traced to a painting scroll in the collection of the temple of Daitokuji. This so-called Daitokuji Shinjuan scroll is traditionally attributed to Tosa Mitsunobu (1434-1525) and is known as the Hyakki yagyō emaki. It may have been based on an earlier model, now lost, and scholars have used other early depictions of the night parade to speculate as to what this earlier model might have looked like. Nevertheless most later depictions seem to have been made with the Daitoku Shinjuan scroll in mind. Michael Dylan Foster discusses the Daitoku Shinjuan scroll in The Book of Yōkai, pp. 45-6.[1]

And there were a lot of later depictions. Many scrolls were made during the Edo Period, and the imagery they contained also made its way into woodblock printed materials. This is, of course, the period when the modern conception of yōkai took shape, but it’s worth noting that the hyakki yagyō illustrations seem to have been treated as a special subset of yōkai. The title of these works refers, of course, to demons (oni 鬼), but while a few orthodox-looking demons appear in the Daitoku Shinjuan and other versions, many of the monsters that populate these scrolls are tsukumogami 付喪神, everyday objects that have gained sentience, sprouted limbs, and taken to frolicking with the demons. Other denizens of these scrolls don’t seem to have stable identities beyond these scrolls, but are nonetheless recognizable as hyakki yagyō monsters due to their specifically medieval costumes. (So distinctive are the monsters from this genre of illustration that some people argue they shouldn’t be considered yōkai at all, but a separate category; since we’re using the term yōkai so inclusively for this digital exhibition we won’t insist on a distinction.)

Many excellent examples of the later scrolls have been reproduced and annotated (in Japanese) in the catalog for a special exhibit at the Mitsui Memorial Museum in 2013.[2] Another Edo-period scroll has been digitized and made accessible online by the Hyogo Prefectural Museum. Note how the artist has utilized the horizontal scroll format to delightful effect: the viewer is treated to a continuously unrolling panorama of monsters. The perfect fit between parade motif and picture scroll is no doubt partly responsible for the many versions of this theme.

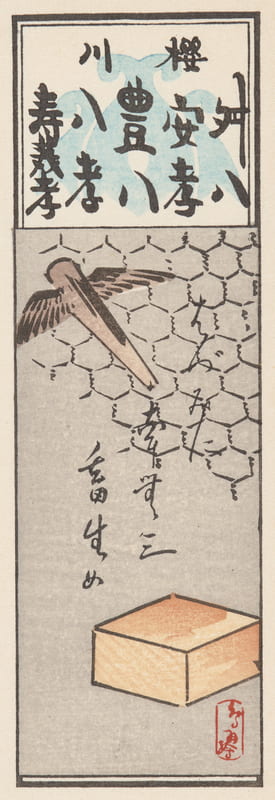

The renfuda format also has obvious potential for depicting processions—just think of the frequent depictions of Kanda parade floats discussed elsewhere. So it’s no surprise that the hyakki yagyō motif shows up. The UO collections contain five one-chō slips that are clearly connected with this theme. Four are obviously from the same series, which raises the possibility that it might have been a complete senjafuda “scroll” of the night parade. The other seems to come from a different series.

The first slip below depicts a red-skinned demon in a courtier’s hat, running or leaping toward the left. He carries a spear on his shoulder. This figure is a standard feature of hyakki yagyō scrolls, and in fact the writing in the ball of flame above him says “hyakki yagyō.” The next four slips also depict figures identifiable from hyakki yagyō scrolls. The figure carrying the ensign with red streamers is probably a monster-fied shoe (as indicated by the black, blue, and yellow shoe tied to its neck). The blue-bodied monster with what looks like a red-handled brush for a head is a monster-fied hossu (used by Buddhist clerics to shoo flies); the same slip shows a woman with a coiled snake for a head, a less frequent feature of hyakki yagyō scrolls. The red, white, and blue streamers attached to a pole (carried by the last demon) are a heihaku, a ceremonial offering used in Shintō rituals. The final slip shows two animated musical instruments: a biwa 琵琶 and a koto 琴.

Some of the best known adaptations were made in the Meiji period by Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-89), a painter and print designer particularly known for his fine touch with the grotesque. Kyōsai seems to have done just about every kind of work an artist of his era could do; see the Enma section for examples of how Kyōsai’s art showed up in senjafuda.

One of Kyōsai’s most fascinating creations was a woodblock-printed book called Kyōsai’s Illustrated Account of a Hundred Demons (Kyōsai hyakki gadan 暁斎百鬼画談), published in 1889, just before Kyōsai’s death. If the Night Parade of a Hundred Demons motif is tailor-made for the scroll format, what is the artist to do if he’s working for book publication? Kyōsai’s solution was to design this as an accordion book: when closed it looks almost like any other book (and can thus be stored alongside other modern books—convenient for those who don’t have a scroll-chest handy), but when unfolded it allows the reader to experience the continuous horizontal format of a scroll. The Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art’s copy of this work may be viewed below. The copy in the Gerhard Pulverer Collection of the Freer Gallery of Art is also available for viewing online, and makes for an interesting comparison.

It provides fascinating context for the hyakki yagyō senjafuda presented above. For one thing, all the figures except the snake-headed woman can be found in Kyōsai’s book. For another, it allows us to place the senjafuda in context as fellow woodblock-printed adaptations of this medieval motif, taking their subject out of the hand-painted world of the scroll and introducing them to the mass-produced world of the modern book, using the techniques of ukiyo-e.

Kyōsai’s book simulates a scroll not just in its horizontal format: it begins and ends with depictions of rolled-up paper, the ends of an unrolled scroll. Note that this trick is also used in the senjafuda “hell scroll” discussed elsewhere on this site. Then the viewer enters a parlor on a rainy night, where a group of people are telling scary stories to each other by candlelight. Food and drink and tobacco are in evidence, marking this as an improvised party. The mist descending over the man adjusting the lamp marks a transition, presumably, into the world of the story being told around the brazier. From this point on we’re in the world of the hyakki yagyō—but it begins with a twist. We first encounter an army of animated skeletons charging into battle. We soon see that their opponents are a horde of nearly indescribable monsters—demons, clearly. From then until nearly the end of the scroll we encounter a recognizable assortment of hyakki yagyō monsters. Note that Kyōsai has reversed the normal movement of the hyakki yagyō scroll—rather than following the procession as it moves to the left, the viewer encounters the procession head-on, as it moves to the right. Coupled with the opening battle scene, this suggests we’re moving through an onrushing horde of demonic reinforcements. The onslaught is only brought to an end by the red sun at the end of the “scroll,” rising to scatter the parade; the sun’s role as savior here may remind us of the way the senjafuda “hell scroll” ends with a bodhisattva’s intervention.

Yasumura Toshinobu has written a full commentary (in Japanese) on Kyōsai’s book.[3]

Tsukumogami are often shown in a hyakki yagyō context, and perhaps for that reason they often have a medieval feel to them rather than a contemporary (i.e., early modern). That is, the objects shown are often those more familiar to medieval viewers than those in Edo, and their clothing or accoutrements are more appropriate to the 12th or 15th century than the 18th or 19th.

Of course, tsukumogami aren’t limited to night parades—Noriko Reider has discussed the broader category of tsukumogami stories and illustrations in the medieval period.[4] And they often appear in early modern yōkai stories and illustrations, too—we’ll see some examples in the boardgame and senjafuda yōkai series sections of this site. Below are some slips that focus exclusively on tsukumogami.

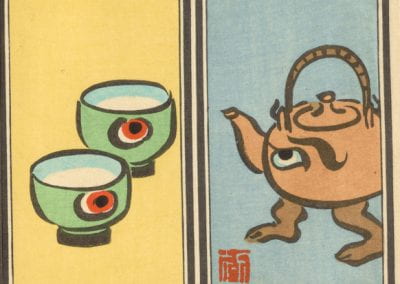

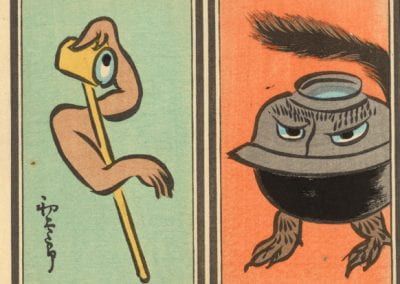

The first four slips below are from a thirty-slip series contained in the Shōbundō Collection. The entire series focuses on tsukumogami, and like these the objects that have become animated are ones that an early modern viewer would still have been familiar with from everyday life. This “modern” sense is complicated, however, by the fact that these slips were made in the early 1950s—they’re expressing a sense of nostalgia for a period when these objects, which by the 1950s might have seemed old-fashioned, still felt new. The art style, however, seems to owe as much to manga as to ukiyo-e, lending these a touch of mid-century modernity to go with the nostalgia. (Of course, in the early 21st century “mid-century modern” is itself an object of nostalgia…)

From left we have: a pair of teacups that together make a set of eyes; a teapot with legs and face; a ladle; a kettle; a shamisen 三味線 holding a plectrum and a songbook; a folding fan wielding itself; and a large mortar and pestle of the type used to make mochi. Note that each pair of slips goes together: the teapot naturally inclines toward the teacups, the ladle would be used to scoop water from the kettle into a teapot, a shamisen player would also have carried a fan (or the shamisen might be used to accompany a second performer who uses a fan as a prop), and the pestle of course is used with the mortar. The viewer might further notice that the kettle’s legs are furry and it has a tail, too; this tells us that it’s not a tsukumogami proper, but a shape-shifting tanuki (see a more orthodox depiction of this tanuki-kettle motif on the sugoroku board).

The final slip is from the Starr Collection and depicts a smaller pestle; there was a vogue for pestle tsukumogami with wings in the 19th century (see also the pestle on the sugoroku board).

The Shōbundō Collection contains another fascinating series that presents yōkai in what seems to be a type of parade (seen above). It consists of six 4-chō slips, each of which has two illustrated panels. Each panel shows one yōkai in silhouette, seen through a backlit paper door. Two of these slips are above. They date from the late 1960s, but the motifs are reminiscent of the vogue for “shadow pictures” (kage-e) in the mid-19th century. Most of the yōkai in this series are presented in profile (perhaps a requirement of the silhouette) and in movement; together they create the illusion of an indoor outbreak of monsters. Perhaps staying behind closed shutters was no protection from the night parade after all.

References

[1] Michael Dylan Foster, The Book of Yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015).

[2] Dai yōkai ten: Oni to yōkai soshite Gegege (Mitsui Kinen Bijutsukan, 2013).

[3] Yasumura Toshinobu 安村敏信, Kawanabe Kyōsai—Kyōsai hyakki gadan 河鍋暁斎 暁斎百鬼画談 (Chikuma Gakugei Bunko, 2009).

[4] Noriko T. Reider, “Animating Objects: Tsukumogami ki and the Medieval Illustration of Shingon Truth,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36.2 (2009).