On this page we are assembling materials that may be useful for the design of curriculum that takes a look at gender structures, relationships, meaning, and performance.

Gender Complementarity

Prehispanic Mesoamerica has been theorized by scholars who see a greater degree of gender balance or gender complementarity between males and females. But hierarchy is also found. There is no consensus as to whether a parallelism was more notable than hierarchical differences. Oaxacan ruler lists, as painted in codices and lienzos, are especially notable for the couples who appear to have a shared rulership or at least a shared status.

- See this example from one of the lienzos of Tequixtepec, where the couple sit on a shared jaguar mat, a symbol of their authority and/or high status.

- Stephanie Wood, “Gender and Town Guardianship in Mesoamerica: Directions for Future Research,” Journal de la Société des Américanistes, 84:2 (1998)

- Geoffrey McCafferty, “Gender Roles,” a full text article posted to Academia.edu

- Shannon M. Peterman (student?), “Effects of Spanish Colonization on Native American Women in South and Mesoamerica,” part of a historiography course, 2013

- Hannah Plumer, “Gender in Mesoamerica: Interpreting Gender Roles in Classic Maya Society,” AnthroJournal, 2011

- The “boying” and “girling” of Mesoamerican children is discussed in Mesolore tutorials about clothing, hairstyles, and (men’s) jewelry

- Mesolore also asks questions on Facebook about why Malinche wears red shoes in many codices and what that might have meant (reproduced below in case the link disappears)

Nahua Gender Ideology

The Nahuas reside primarily in central Mexico, and have for hundreds of years, but they also had colonies in what is now the state of Oaxaca. If you would like to take a look at a range of vocabulary that highlights male and female roles, status, occupations, etc., in the Nahuatl language, follow this search in the online Dictionary.

Masculinity

Many people stereotype Mexican culture as “macho,” notably or even excessively masculine. For those with an interest in gender and the Mesoamerican cultures and their histories, it might be interesting to explore gender constructs in prehispanic cultures and how those constructs changed with colonization by Europeans — a colonization that lasted (overtly) for three hundred years, and really continues to the modern day if one accepts the presence of neo-colonialism (with its U.S. influences, among others).

- “Machismo” in Wikipedia

Lucha Libre

The Lucha Libre wrestler is pervasive in popular culture across Mexico. Colorful masks characterize a prominent component of the costume of these luchadores (fighters), and for some observers, there is an appreciation for anonymity and the working-class struggle.

- Javier Pereda and Patricia Murrieta-Flores have posted a copy of their essay, “The Role of Lucha Libre in the Construction of Mexican Male Identity,” on Academia.edu

- Evan Pereda, “Mask and Masculinity: Culture, Modernity, and Gender Identity in the Mexican Lucha Libre films of El Santo,” free full-text essay on IngentaConnect

- Some luchadores, called “los exóticos,” maricones, or jotos (terms for gay men) wear drag. These figures add nuance to the masculinity of the lucha libre phemomenon. See the Wikipedia article as a start.

One can also find online an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe with a lucha libre mask, a feather aura, and a woven snake belt like that associated with the goddess Coatlicue. It is an art piece created by Guadalupe Rodríguez in 1995. She titled it “La Luchadora,” (The Fighter), probably as a reference to her perception as one who works on behalf of those who are less fortunate in life.

Marianismo and Femininity

- “Marianismo” in Wikipedia

- “Latinas and Modern Marianismo,” Huffington Post (2013)

- Carmen Román, “Machismo and Marianismo: New Models for Old Patterns,” Time-2-Track blog (2012)

Muxes

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec, state of Oaxaca, is known for having a “third gender” (as some call it). People who fall somewhere on the continuum between male and female are referred to as “muxes” (pronounced MOO-shays). Some say they are “men” who think of themselves as “women.” Since the culture of Tehuantepec is Zapotec at its heart, one might find a study of the muxe (said to be a Zapotecization of the Spanish word mujer, woman) interesting for understanding gender constructs in that indigenous society and how they have evolved with contact.

- Marc Lacey, “A Lifestyle Distinct: The Muxe of Oaxaca,” New York Times (2008)

- “Stunning Portraits of Muxes — Mexico’s Third Gender” ColorLines (2013)

- Wikipedia article on the “Muxe“

- “Mexico’s Third Gender,” a 22-minute video on YouTube in Spanish with English subtitles

- “Queer Paradise,” a 2.27 minute video on YouTube about muxes and expressions in Zapotec, also other labels for similar gender typing in other parts of Mexico, in Spanish with English subtitles

Mexican Female Icons

Female icons in Mexican ethnonationalism are actually very abundant. How they are represented and what they mean to men and women are open to interepretation. Just a few to follow across Mexican history are:

- Marina/Malintzin/Malinche — a Nahua woman who was “given” to Hernando Cortés, worked as his interpreter in the conquest march, and had to bear his child). She has has been vilified by some for giving Spaniard the keys to the kingdom, while others assert that she was a slave who had no choice. Some see her as a “mother of mestizaje” (mixed heritage children, symbolic of “all” Mexicans).

Lienzo de Tlaxcala detail, shows Malintzin interpreting as Cortés and Xicotencatl meet and arrange their alliance. Shot from a facsimile in the Fundación Bustamante, Oaxaca. (R. Haskett, 2009)

Many images of Malintzin appear in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala and other indigenous-authored manuscripts. In sixteenth-century records, even those authored by Nahuas (defeated by the Spaniards and Tlaxcalans) she is treated with great respect. We also see her carrying a bundle and resting in one scene, possibly a reminder that she was a slave to Cortés, even though she was probably of noble origins.

Curricular unit: “Doña Marina: Cortés’ Translator,” Women in World History, with primary sources (Cortés, Bernal Díaz del Castillo), teaching strategies, lessons, document-based question, bibliographyk, printable versionsl, credits, and short essays on the topic

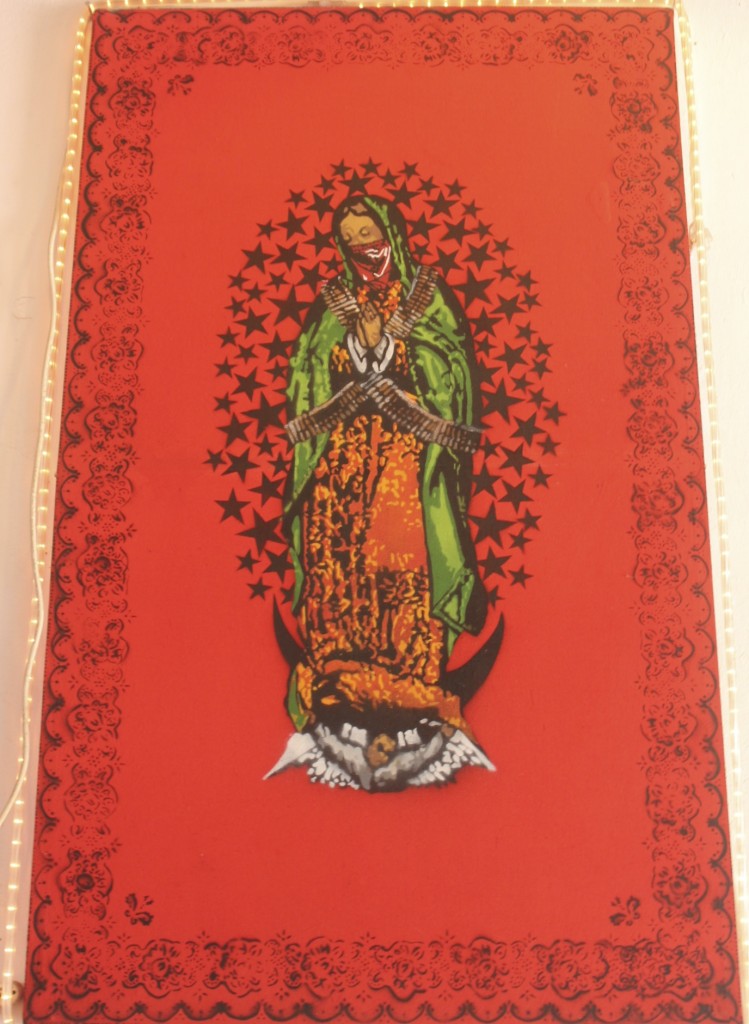

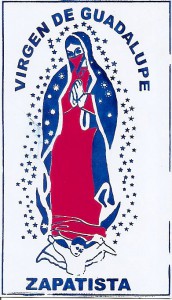

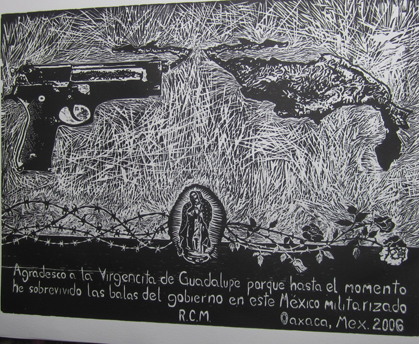

- Virgin of Guadalupe — this is the name for the Virgin Mary of Christianity, who is believed to have made an apparition in Mexico in 1531, speaking Nahuatl to an indigenous youth, Juan Diego (now officially a saint in the Catholic church), and who is said to have brown skin (“la morena”). Her indigeneity might be perceived as ironic. Was her apparition symbolic of God’s approbation of the Spanish conquest and colonization of Mexico, as some believe? Was she promoted to try to win the indigenous people over to the new faith? How has she come to be associated with the underdog? The Virgin of Guadalupe, for many, is also the supreme representation of marianismo (purity and moral strength).

“Tonantzin” means “Our Mother” (a reverential expression) that Nahuas used to refer to their goddesses and to the Virgin Mary (Guadalupe) after contact with Europeans. To follow the links in the Spanish-language, visit Red Mexicana de Arqueología.

Pinterest has an image of a Mother Earth/Tonantzin (literally, “Our Mother,” in the reverential). This links the Virgin of Guadalupe with an indigenous goddess.

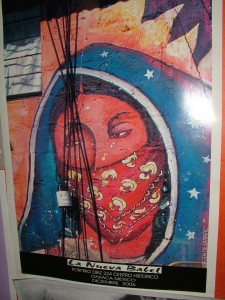

Virgin of Guadalupe transformed into the Virgin of the Barricades commemorating the 2006 social movement in Oaxaca. By Wons and Line. (R. Haskett, 2009)

Here’s a representation of the Virgin of Guadalupe in a piece of street art from 2014 by a “Mr. Skelleton,” with the caption, “Pueblo Rebelde” (rebellious community or rebellious people). Image thanks to Noé Riojas:

For an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe surrounded by a quincunx flower arrangement reminiscent of maize, see the online photo relating to the “Día de la Tierra” (Earth Day) in Cuernavaca and Amecameca, Mexico. And, for more about the quincunx, see our STEM page, and the astronomy subheading.

See also Xicana artist Melanie Cervantes’ art piece with the Virgen of Guadalupe as “Mother Earth.” The figure is a campesina (rural indigenous woman) with an aura made of maize cobs and two serpents at her feet.

“Lupita” (the nickname of the Virgin of Guadalupe) painted affectionately on a Volkswagen bug, Oaxaca. (Photo, S. Wood, 2009)

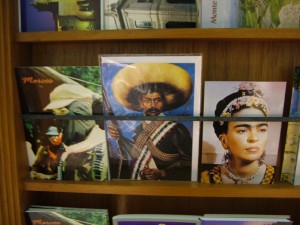

Mexican icons, the Virgin of Guadalupe and Pancho Villa, side by side. Women’s Art Collective, Oaxaca, 2010. (S. Wood)

- Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651–1695) was a Hieronymite nun who became famous for her intellect and her writings. In a time when a woman’s literary practice was rare, she has been a much celebrated female exception. Wikipedia has a biography of her. EDSITEment! offers lessons about her sonnets in both English and Spanish. Dartmouth college has a complex website devoted to Sor Juana, Oregon State offers a timeline, and Luis M. Villar has compiled an extensive bibliography about her.

Some like to think Sor Juana was a lesbian, as is suggested by the film, Yo, La Peor de Todas/I, The Worst of All (the complete film is available on YouTube). Others reject the idea emphatically. The whole debate reveals strong feelings about the possibilities of homosexuality in history and today. But, as David Foster writes in his book, Latin American Writers on Gay and Lesbian Themes, “What really matters is that, in spite of the extreme limitations of her time and society, she managed to communicate her elusive feelings with sensitivity and talent and to provide a testimony of resistance to male prerogatives” (1994, 197). It is for that reason, primarily, that she has become a Mexican icon and a global feminist icon.

- La Adelita is a prototype of the female in the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Wikipedia has an article about this figure, including lyrics to a famous song about her. The song can also be heard on YouTube in many renditions. “Adelita” was the name of a woman much romanticized in this famous ballad about the Revolution, and the name has been extended to the generic women revolutionaries of that period, as “Las Adelitas.” Women in the Revolution of 1910 played many roles, from fighting (rare), to supplying troops, cooking, washing, nursing, and providing or selling sex to the men, and more.

Classic “Adelita” image (probably not really her name). Click here or the fuller image. Photo of images for sale, Mexico City, 2002. (S. Wood)

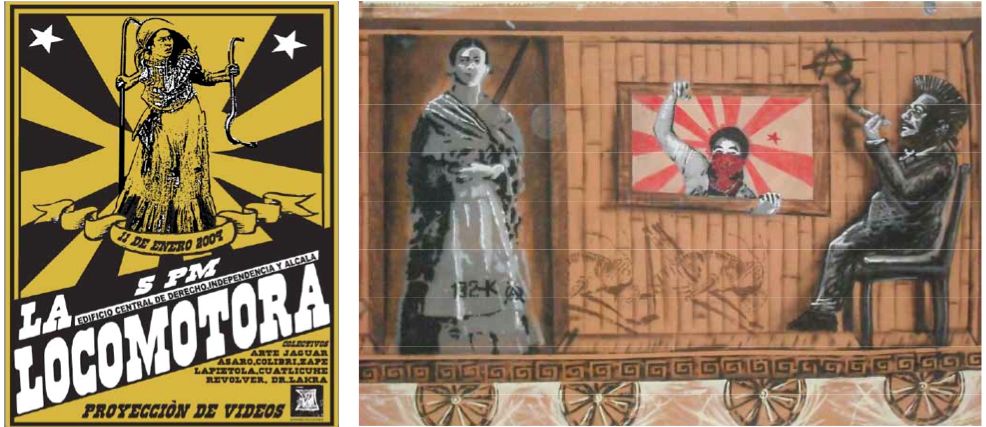

Adelita with a face mask, associated with the social movement in Oaxaca, 2006. By Beta, of ASARO. (From an interview with an ArteJaguar visual artist on YouTube.)

Adelita in a take-off from the historical photo (left) and a version of Frida’s self-portrait as an “Adelita” revolutionary (right). (Photos, ASARO)

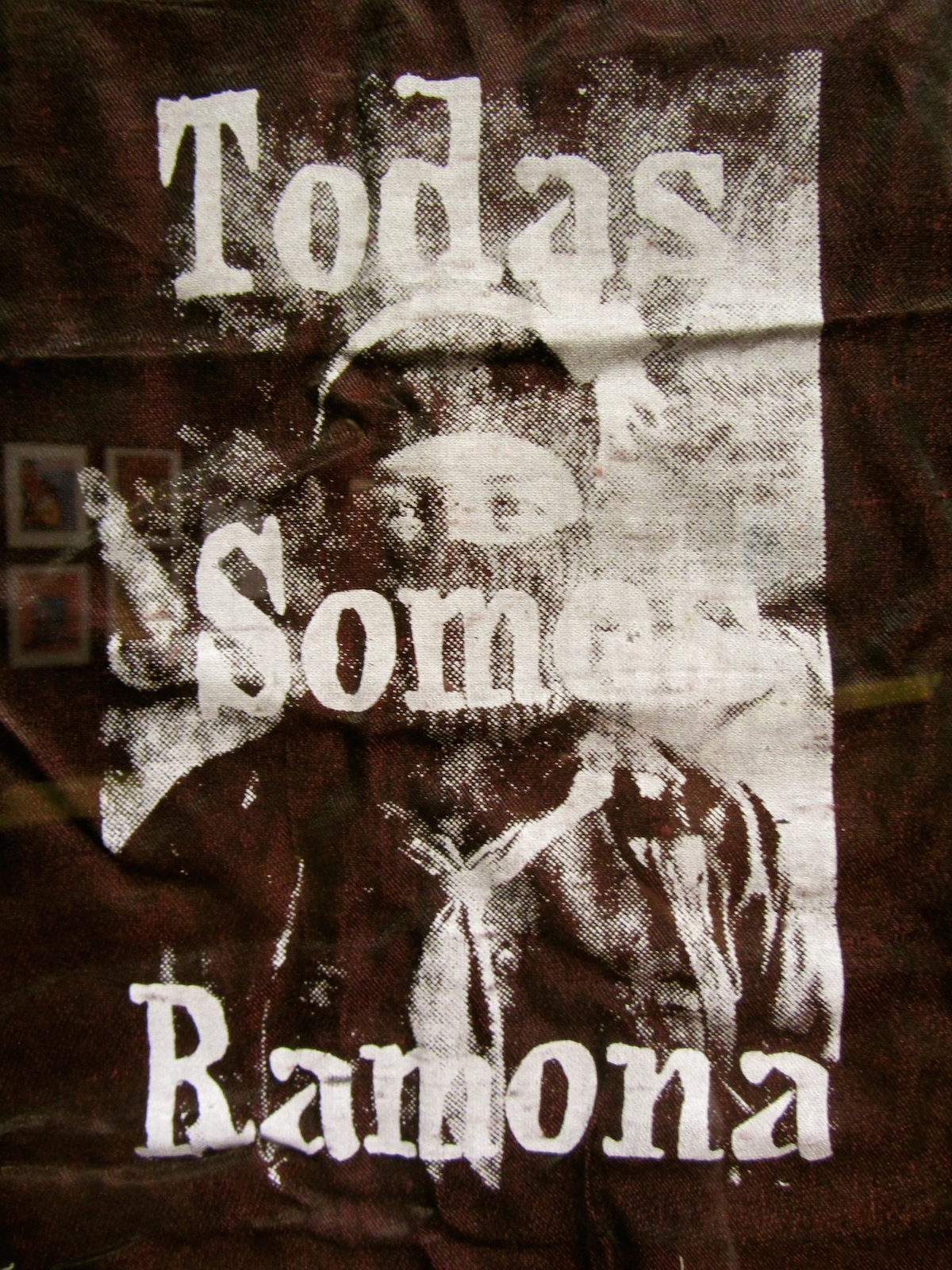

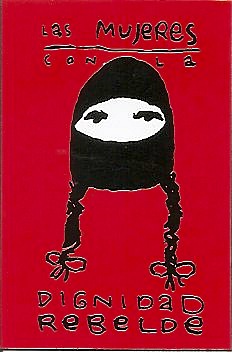

- Comandanta Ramona (1959–2006) — A more recent revolutionary female figure is “Ramona,” a Tzotzil Maya leader of the Zapatista movement in Chiapas in the 1990s, born near San Andrés Larrainzar. A Wikipedia page is dedicated to her story. Nicole Morales wrote an article about her, “Adventures in Feministory: Comandante Ramona,” in Bitch Magazine in 2011, which is still free on line in full text. Murals have been painted with her image (usually wearing a red scarf over her nose and mouth) or a black knit ski mask. Here is another painting of her. She also wore a red-on-white, handwoven huipil (indigenous women’s blouse) and was known to carry red roses (also symbols of the Virgin of Guadalupe). When she passed away, an obituary published in Argentina shows her holding lilies, instead. Candles burn for her in an altar-like mural in El Paso, Texas. Now, as something of a martyr, images of her are generally very sweet. Ramona is noted for having helped write the “Women’s Revolutionary Law,” for the autonomous zones of Chiapas, which, if ever fully implemented, would dramatically change the lives of indigenous women. Some changes have already begun. A commemorative postcard suggests that we look and listen with our hearts and strive for a Mexico where all people have a dignified place.

“Comandanta Ramona” — name given to a breakfast item. Cafe Lobo Azul menu, Oaxaca. (S. Wood, Nov. 2013)

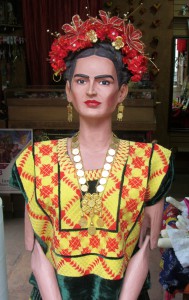

- Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) — Kahlo was a painter who liked to say she was born with the Mexican Revolution of 1910. She was married to the famous muralist, Diego Rivera, but she preferred reflexive, self-portraits over large murals about the Revolution. She did link herself to revolutionary figures and symbols, and some now hold her up as the female counterpart to the quintessential Latin American male revolutionary, Che Guevara. Was she a “feminist” who celebrated the strong women of Tehuantepec? Although she was married, did she have sexual relationships with other women? These are questions that artists have explored in re-creating images of Frida Kahlo. She and Diego loved going to the state of Oaxaca, especially the Isthmus of Tehuantepec where they were fascinated by the strong Zapotec women they got to know there. They influence Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein to make the film Que Viva México! with a segment shot in Tehuantepec, Frida often wore the Tehuana dress, and Diego painted scenes of dances in Juchitán. Oaxacan artists have been recasting Frida as a punk figure in recent times, translating her image into one for a more youthful consumption. They have also made her into a graffiti artist, putting a spray-paint can in her hands.

Screenshot of Frida Kahlo represented as a street artist with an aerosol can. (from Facebook, June 2013)

Frida Kahlo with monkey and cigarette, by Ektas of Zaachila, Oaxaca. (Photo, Itandehui F. Orozco, n.d.)

- María Sabina (1894?–1985) is a Mazatec woman who was a shaman, the most famous shaman from the state of Oaxaca. She has also become something of a national icon in Mexico among youth interested in psychedelic mushrooms and curanderismo (indigenous healing methods). In the 1960s and 70s, she attracted thousands of foreign youth seeking a mushroom experience. She met with music legends John Lennon, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger, and Bob Dylan, among others. For her, mushrooms were “holy children,” and they were primarily meant for curing the sick. She became disillusioned by other uses. Her chants, spoken in Mazatec while in a psychedelic state, were translated and published. Here’s a sample:

Because I can swim in all forms

Because I am the launch woman

Because I am the sacred opposum

Because I am the Lord opposum

I am the woman of the populous town, says

I am the shepherdess who is beneath the water, says

I am the woman who shepherds the immense, says

I am a shepherdess and I come with my shepherd, says

And I come going from place to place from the origin…

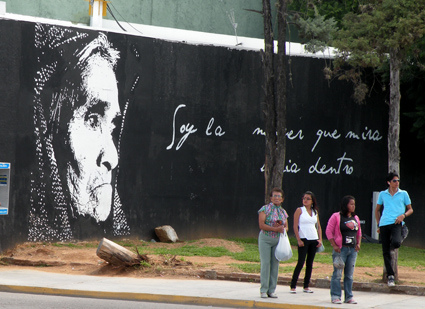

Mural by Ana Santos showing María Sabina. Quote translation (loosely): “I am the woman who looks inside.” (Photo, Itandehui F. Orozco, 2012)

María Sabina by street artists Cer and Vain, in Puebla, Mexico. Arte Jaguar. (Photo, Itandehui F. Orozco, 2007)

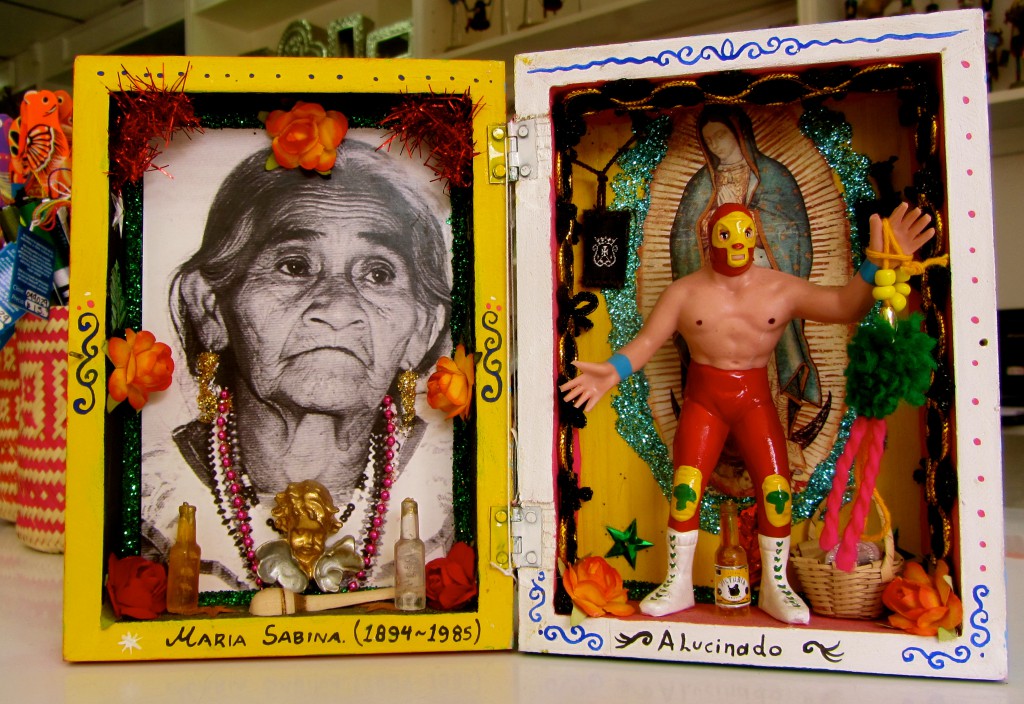

A nicho piece with María Sabina, Lucha Libre, and the Virgin of Guadalupe — three icons rolled into one. (Photo, S. Wood, July 7, 2014, Oaxaca)

Feminist Street Art

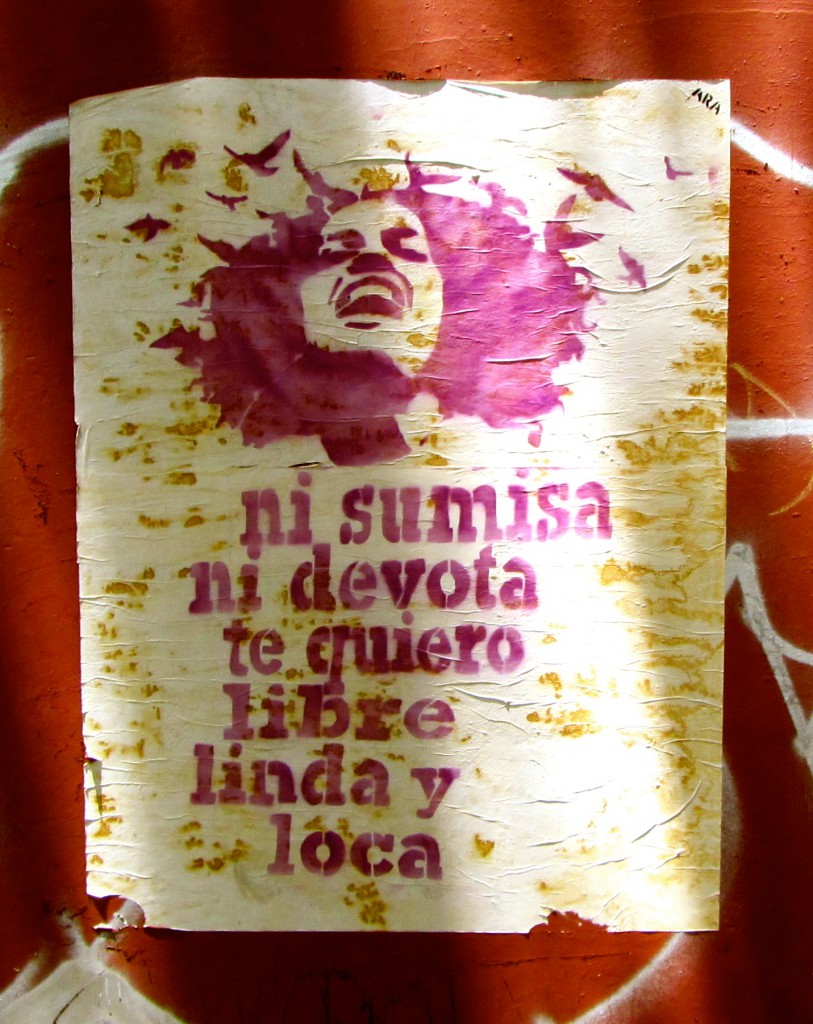

This first example appears to have been authored or created by a male street artist, but one never knows. It could be a message from a woman to a woman.

“Neither submissive, nor devoted; I love/want you free, beautiful, and crazy.” (Oaxaca poster, seen July 2014)

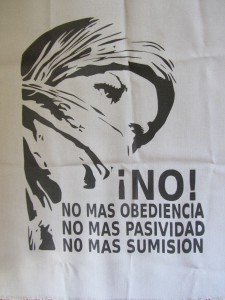

Artist Mojo’s print on cloth. “No! No more obedience. No more passivity. No more submission.” (Photo, S. Wood, Oaxaca, 2014)

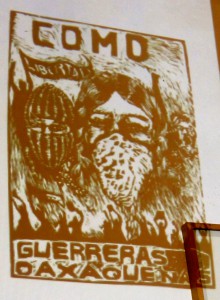

Oaxacan woman warriors. An ASARO piece celebrating the women’s group COMO from 2006 – 2007. (Photo, S. Wood, 2014)

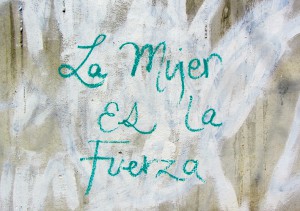

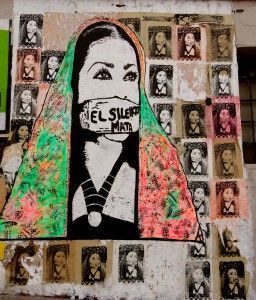

Below, former NEH Summer Scholar Elise Weisenbach provided these two examples of feminist graffiti from the state of Chiapas, Mexico, that she shot while taking part in a Yale-based summer institute. She makes it available for your use in curriculum development.

Street art productivity is dominated by men, but there are a few women, and numbers are growing (slowly). Of course, men also sometimes treat feminist issues.

Feminist piece by Tlakolulokos, Oaxaca street art group (from their website). Screenshot, Jan. 2014.

Note how the women are dressed and are wearing their hair as though they are indigenous women. (This street-art group is from the Zapotec town of Tlacolula, in one of the valleys in the state of Oaxaca.) But, the women have tennis shoes, dark glasses, and face masks. They are purposely placed in the barricades of the 2006 social movement in Oaxaca. The “fuck you” attitude seems to reflect their intended stance. Why is this expression in English? The reason may be that many of these youth have at various points lived and worked in the U.S. Or maybe their message is directed at gringos–?

Femicide/Feminicide

We are seeing increasing attention in art forms across Mexico to the femicide or feminicide that tends to be concentrated in the border region, especially around Ciudad Juárez. Figures of women and the symbol of the cross is very prevalent in these works.

Casa de la Mujer

Oaxaca has many NGOs that work for the advancement of indigenous women. The Grupo de Estudios de la Mujer at the Casa de la Mujer puts emphasis on furthering the education of indigenous girls, who rarely get beyond elementary school because it might mean having to leave their communities — something their parents are reluctant to permit, given the cost, the need for their help at home, and/or the fear of a risk to their daughters’ purity. Currently, the GES-Mujer is providing scholarships to 21 girls, helping them (and their families) financially, making it possible for them to stay in school through middle school and/or high school. Some of the becarias (girls on scholarship and the alumni) are even now getting university educations, such as Reyna, in environmental studies at the UNAM, or Gabriela, studying law.

The Casa provides weekend workshops, when the girls come to learn about feminism, to develop leadership, and have their aspirations raised for their own futures.

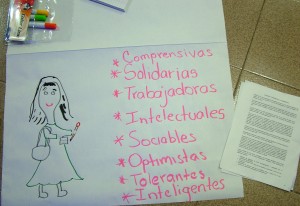

Feminist workshop at the Casa, 2008. Girls were asked to think of women with positive adjectives (such as hardworking, intellectual, intelligent). (Photo, S. Wood, 2008)

Mesolore

Mesolore offers a web page about gender in Mesoamerica with links to a number of audio podcasts of more or less than ten minutes each exploring whether we should even address gender issues, political correctness, and women’s (in)equality. These are leading scholars who have published on these topics, such as Elizabeth M. Brumfiel, Rosemary A. Joyce, and Susan Kellogg. All are in English with the exception of Alfredo López-Austin’s piece about the body.