On this page we are assembling resources of possible use in designing curricula around the theme of dance in Mesoamerica across time. Some of the images can be enlarged (by clicking on them).

Pre-Columbian Dance Forms

Possibly Pre-Classic Nayarit (or West Mexican) house in pottery. Private collection, Oaxaca. (S. Wood, 2010)

Note the group (above) forming a circle in the middle of the onlookers. They put their hands on one another’s shoulders, and they appear to be dancing. Another West Mexican pre-Columbian piece (ca. 300 B.C.E. to 900 C.E.) also shows what are perceived to be dancers and musicians in a circle. Yet another piece, from Nayarit (ca. 100 B.C.E. to 400 C.E.), with a similar circular formation, is said to represent a group of dancers. From late Pre-Classic Colima (ca. 300 B.C.E. to 250 C.E.), another part of West Mexico, we know of a row of dancers, led by a flute player. Ian Mursell also provides an image of what appears to be a circular dance from Colima, asking, in his short study, whether these formations survived the Spanish invasion and colonization. One could make an interesting study of these ceramics from Pre-Classic and early Classic West Mexico, which seem to reveal wonderful details of daily life.

Another source for studying pre-Columbian dance forms is represented by the extensive number of what may be dance figures from late Classic Veracruz (below).

This is said to be a dancer represented in pottery from Classic Period Veracruz. Museo Rufino Tamayo, Oaxaca. (S. Wood, 2010)

Classic-era Veracrus. Women and girls in a “posture” as though dancing (holding their skirts). Museo Rufino Tamayo, Oaxaca. (S. Wood, 2010)

Detail. The lines in this woman’s face may be a suggestion that she is an older woman. (S. Wood, 2010)

As the examples show (above), the Museo Rufino Tamayo would be a good place to look for artifacts of relevance for studying prehispanic Mesoamerican dance. Notice how, on the Gulf Coast from about 600 C.E. to 900 C.E.), the female dancers wore skirts but no tops, just necklaces. The climate in Veracruz is warm, generally, which might explain the lack of blouses. The skirts show geometric patterns reminiscent of textiles still found today in places such as Oaxaca. They might also remind us of the stone mosaics at Mitla. Yet, any connection to Oaxaca may be coincidental (although the two states, today, do share a border).

Also note how the Gulf Coast/Veracruz dancers wore sandals, and they wore something in their hair. They possibly kept their hair short and rectangular in shape. Some may have grown up with cranial deformation (a flattening of the forehead). Skulls in the graves related to this region and period also show this artificial deformation. A tilting of the head backward, as may be the case with some of these figurine, may have increased the effect of the sloping forehead.

In many of these figurines from Late-Classic Veracruz, the dancers appear to have been smiling broadly. Archaeologists refer to these figures as “sonrientes” (Spanish for smiling figures), and there are many theories about the smiles, but none of the conjectures has been proven.

Since these figures in the Rufino Tamayo museum have a weak provenance, they were probably looted. But in the years after this collection was made, new excavations have brought to light many more ceramic pieces linked to specific sites and stratigraphy in Veracruz, especially from the late Classic-Period culture (of which these figures may be a part). Here are some more images of these figures. While some (above) have their hands on their hips, others have their arms extended. See also Richard Diehl’s article at FAMSI that includes information about the smiling figure.

Colonial Indigenous Dance Forms

A painted, folding screen from 1690, has a wonderful dance scene in front of a Spanish colonial church. The wedding of an indigenous couple is taking place in the Nahua community of Santa Anita Iztacalco. Outside the church we see indigenous dancers performing a dance that memorializes the time of Moctezuma, who appears in the group wearing a large, green, feathered headdress and carrying a macana (obsidian-blade studded club).

Folding screen detail, showing a dance. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (Photo, R. Haskett, 2010.)

Note the harp and the stringed instrument on the left. The dancers also carry bundles of feathers.

Music and dance forms in New Spain (colonial Mexico) frequently preserved — and sometimes reinterpreted — indigenous themes. In the image above, from Joaquín Antonio de Basarás y Garaygorta, Origen, costumbres, y estado presente de mexicanos y philipinos (1763), lam. 3, 118, we see the Dance of the Emperor Moctezuma. Note the band playing on both the right and left, and the use of headdresses and feather adornments.

Music and dance regularly accompanied theatrical performances, which is the subject of a wonderful online essay by Diana Taylor, “Scenes of Cognition: Performance and Conquest,” with wonderful illustrations.

The late-colonial dance below, from a painting ca. 1780 (Museo de América, Madrid), is said to be a “danza de los indios (mitote)” (a dance of the indigenous people, called a mitote). Mitotli was the Nahuatl word for dance, and the replacement of the ending -tli with -te was typical of the Hispanization of Nahuatl. Still, what is called the mitote dance today is believed to be an indigenous dance from communities in the Sierra Madre mountain range. It is remarkable that these dances lived on as long as they have (still to the present). Does the fact that a dance such as this was painted suggest that the painter held a special appreciation for it? Could this memorializing be an early example in the development of “folklore” or even an indigenous cultural revivalism?

The feather headdresses vaguely recall indigenous culture, but the clothing of the dancers is very much influenced by European styles. The king or emperor wears a crown that is very much in the European style. Can we make anything of the heavy embroidery of the women’s blouses and skirts? Wealth is suggested by the pearl necklaces. Were the colonial elite embracing dances of indigenous peoples?

Mitote dance representation from 1780, Los Angeles County Museum exhibition. (Photo, R. Haskett, 2010)

Early Twentieth-Century Music and Dance

Below we see dancers wearing the feathered headdresses which may pertain to the Danza de la Pluma (Feather Dance) of Teotitlán del Valle. This is a slide shot in the 1930s or 1940s in the state of Oaxaca by a late University of Oregon Spanish professor. His slides are now in the Wired Humanities Projects collections.

Danza de la Pluma? Teotitlán del Valle? ca. 1930s or 40s. Photographer unknown. Slide in WHP collections.

Danza de la Pluma? One could share these images with people in Teotitlán del Valle to inquire if they recognize the dance and the dancers.

Dance in Contemporary Oaxaca

The Guelaguetza dance festival is another natural resource for studying more current dance forms in the state of Oaxaca. Notice how the women hold their skirts, reminiscent of the pre-Columbian figures from Veracruz (and perhaps dancers in many parts of the world, at many points in time?).

In the scene below, from the Guelaguetza street parade, we see a detail of the way women from Juchitán, a Zapotec community in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, adorn their hair, wear coin necklaces, and carry colored candle-lanterns. At night, the lanterns are lighted. The blouses of women from Tehuantepec are elaborately embroidered in a rectangular pattern that becomes easily recognizable; it has a deep history, too. Mexican muralist Diego Rivera memorialized the Zapotec Tehuana (female from Tehuantepec), as did Frida Kahlo, who liked to wear the Tehuana dress.

In the detail below, we can see how some of the dancers in the Guelaguetza weave colored ribbons into their braids. Braids themselves are now a type of hairstyle largely confined to indigenous women, and the peasant blouses, too.

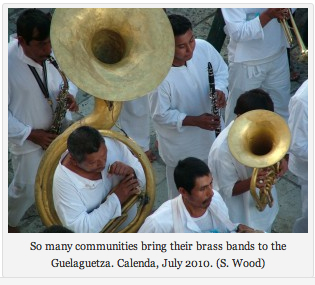

Brass bands are very common in indigenous communities across the state of Oaxaca today. They became prevalent in the nineteenth century.

Mexicolore Curricular Materials

- “Did Precolumbian Dances Survive the Conquest?” (Ian Mursell)

YouTube Videos about the Guelaguetza Dances

- Guelaguetza Calenda (Parade) by Gabriela Martínez: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5EnFiuzmD14

- Huajuapan dance festival, 2007, in slides (introduction in Mixteco), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ipQEwI_UO0

- Járabe Mixteco (from Huajuapan) (5 min.) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Pzyt4CnyNI

- Guelaguetza Dance show at Quinta Real Hotel by Vinny Civarelli Jr.: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLmuGyKH0OCew_RYh-JzalZQRCo2yx204y

- there are many more; you can Google these

Curricula from Former NEH Summer Scholars in Oaxaca

Lindsay Mitchell – High School Spanish 4 & 5 – “Los mitos y leyendas del mundo mesoamericano” — the Donají component relates to the Guelaguetza dance festival, where the legend is regularly performed

- Unit Information (DOC)

- Mitos escritos (DOC)

- Short myth handout (DOC)

- Donají leyenda (DOC)

- Donají handout (DOC)

- Myths and Legends sorting activity for smartboard (DOC)

- Los mitos y leyendas del mundo mesoamericano (PPT)

- Chatino interview – Video (WMV)

See also our pages about the Guelaguetza and Ethnomusicology.