The pre-Columbian Nahuatl (Aztec) word for paper was amatl, which became amate in Spanish. By extension, amatl also served as the word in Nahuatl for letter and document. The closest word for book was amoxtli. We might translate amoxtli as codex. A codex was often screen-folded, like an accordion, in pre-Columbian times and some early colonial examples also have this design.

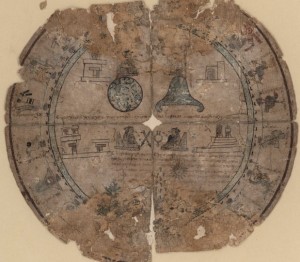

Indigenous-authored manuscripts from Spanish colonial days show various influences from European traditions, while they also retain Native ways. Here is a codex on amatl, called in English the Boban Calendar Wheel:

This manuscript is not screenfolded, but it is largely pictographic. You can also see alphabetic texts (in Nahuatl), authored after contact with Europeans. The Spanish clergy taught the indigenous elite males to write in their own languages (but primarily in Nahuatl) with the Roman alphabet. Besides amatl, indigenous-authored manuscripts from colonial times were painted, for example, on hide, other natural plant fibers, and European paper.

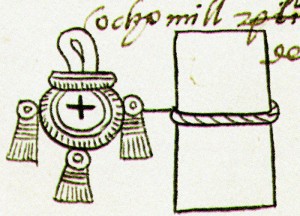

Codex Mendoza detail showing that 8,000 pages of bark paper were a tribute item. (from Mexicolore)

Europeans and indigenous communities in pre-contact Mesoamerica both had paper, upon which they wrote and painted. The Codex Mendoza shows paper as an item that was probably required to be provided to the Aztec emperor prior to contact and, more certainly, was an item required to be paid to Spanish colonial overlords. The number 8,000 comes from the glyph for the “xiquipilli,” which was a ceremonial bag that perhaps once contained 8,000 (or, a large number of) cocoa beans. We have also seen xiquipilli (bags) with incense in them.

The Nahuas both prior to contact with Europeans — and still today in some communities — included specially-cut papers in their religious ceremonies. A Wikipedia article about amatl tells of the modern paintings on amatl that you will see for sale on the streets of Oaxaca (brought by amateros from the state of Guerrero). See also our special page on amate paintings.

Cut amatl from an Otomí community, more akin to pre-Columbian patterns than the amate paintings sold on the streets of Oaxaca today. (From Wikipedia, amatl site.)

Below are some modern lamp shades made with amatl.

Dried flower imbedded in amatl. Exhibition at the Centro de las Artes San Agustín (Etla), November 2013. (Photo, S. Wood)

Modern Mexican paper arts that seem to stem from these traditions include colorful tissue-paper streamers connected by string and hung from the ceiling on special occasions. This is called papel picado in Spanish.

The paper-making workshop in San Agustín Etla is a must-stop for those interested in studying paper in Mesoamerica. Below, one of the workers explains the ingredients that are used for making paper.

For more images from the paper-making workshop, please see our page on the excursion to San Agustín Etla.