The purpose of this section of the website is to assemble resources for building curricular units around indigenous-authored pictorial and textual documents. We will divide some of the sub-topics into their own pages.

In English, the term “codex” (códice, in Spanish) refers to a pre-Columbian or sixteenth-century post-contact, indigenous-authored book or manuscript. They are typically both pictorial and textual. Over the three hundred years of the Spanish colonial period, indigenous authors/painters continued to produce manuscripts, some of which are called codices (plural/English, or códices, plural/Spanish), and some of which are called “mapas,” “lienzos,” and by other labels. These are usually both pictorial and textual, too, although sometimes somewhat more textual or somewhat more pictorial.

Oldest American Book

Some scholars refer to the Dresden Codex, from the 11th or 12th century, as the oldest existing American book. One of three indisputable pre-Columbian Mayan manuscripts, the Dresden may be a copy of something that was three or four hundred years older. The screenfold manuscript, currently held in the Saxon State Library in Dresden, Germany, treats Yucatec Maya calendrical-astronomical cycles, rituals, and ceremonies. It is associated with Chichen Itza. The FAMSI website offers links for downloading different versions of the manuscript.

Copies of additional codices for downloading can also be found on the World Digital Library (search, for example, codex Mexico, to retrieve a long list), Amoxcalli, and elsewhere on line. The Mapas Project offers commentary on details of indigenous-authored pictorial manscripts from the Spanish colonial period in Mesoamerica, plus transcriptions and translations of texts.

Early Post-Contact Codex

Below, we see a page from the Codex Mendoza (also called the Códice Mendocino in Spanish), which is a sixteenth-century Nahua codex that retains much from pre-Columbian traditions, having absorbed few European influences. It was made only about two decades after Spanish colonization. It was sent by ship to the King of Spain, but French pirates attached the fleet, and it ended up in France. Finally, it ended up at Oxford University. On this scene, below, we see the story of a vision or prophecy of an eagle on a cactus, a clue that would let migrants from Aztlan know that they were about to find their fated destination, Tenochtitlan, the name for what is now Mexico City. We also see symbols of Aztecs conquering neighboring communities as they built their own empire, prior to the Spanish invasion.

Prehispanic Codices Represented

In this section you will see how Maya writers/painters are depicted in pre-Columbian ceramics. These scenes are a wonderful window onto early writing and painting methods of the specialist-scribes. We see their postures and how they were dressed (headdresses, loincloths sometimes of animal skins, etc.). The fact that painting and writing was memorialized in scenes painted on pottery helps us understand the importance of such an activity.

Classic-Period Maya vase, showing Hero Twins of the Popol Vuh origin story writing in codices. K1523. (Justin Kerr, Mayavase Database, with permission)

Vase showing scribes holding codices with paint pots. K5352. (Justin Kerr, Mayavase Database, with permission)

Vase showing old scribes holding codices. Classic Maya. K760. (Justin Kerr, Mayavase Database, with permission)

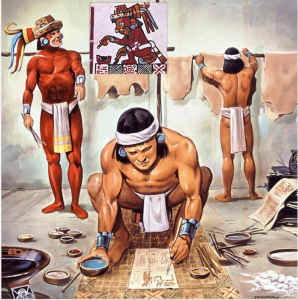

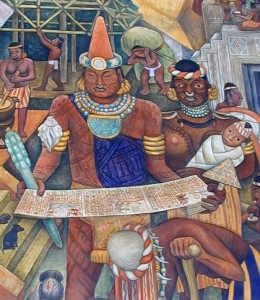

Below, we see how contemporary artists have imagined pre-Columbian codex-making activities:

Arqueología Mexicana, June 11, 2014, Facebook post. Imagining how codices were painted in pre-Hispanic times. Hides are also being prepared in the background.

Prehispanic screenfold codex as imagined by Diego Rivera in a twentieth-century mural in the National Palace, Mexico City. (S. Wood, 2003)

For a brief discussion of some prehispanic Mesoamerican screenfolds, see this Mesolore page.

Municipal Palace Mural

In another twentieth-century mural, below, from the municipal palace in Oaxaca, artist Arturo García Bustos inserted details with design elements reminiscent of prehispanic codices.

García Bustos also includes what may signify an indigenous town-founding couple. Founding “mothers and fathers” were much more the norm in Mesoamerican communities than our “founding fathers” (which omits the female principle). See our Gender page for further discussion of the theory of Mesoamerican complementarity.

Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca, Santo Domingo

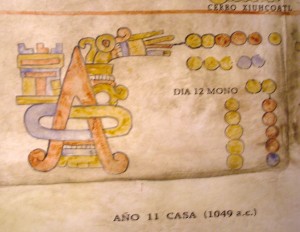

The museum upstairs in the Santo Domingo cultural center has some reproductions and studies of codices, such as the Códice Alfonso Caso (or, in English, Alfonso Caso Codex), which has as its focus the caciques who vied for power in the Mixteca in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

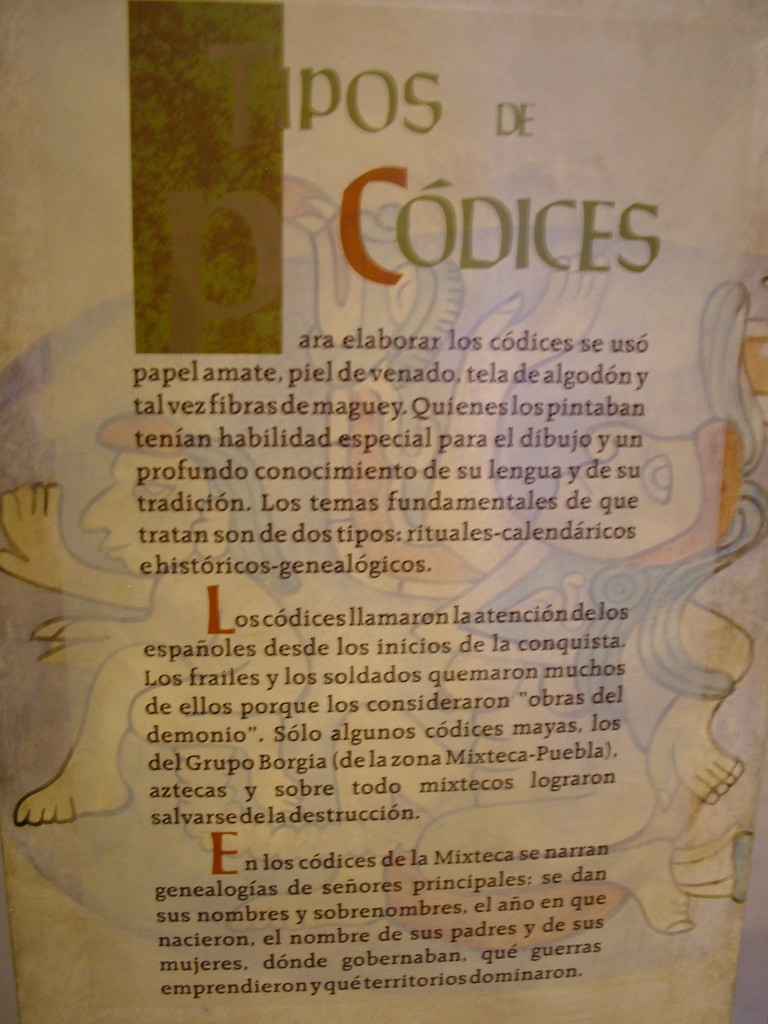

Codices could be made on amatl, on paper made from maguey, on hide, cloth, and other materials. Very few (perhaps 20) pre-Columbian codices escaped being burned by zealous Christian friars who were a part of the Spanish invasion and colonization of Mexico in the early sixteenth-century. Mixtec codices, according to the museum sign above, narrate the genealogies of the principal lords, their names and titles, the dates of their births, the names of their parents and their wives, where they governed, what wars they started, and what territories they dominated.

Colonial Changes and Continuities

One of the greatest concerns that arose with the Spanish invasion was the burning of codices by some zealous friars. (Fortunately, for history and posterity, other friars supported the preservation and creation of indigenous-authored manuscripts in order to study the pre-Columbian cultures.) Below is a work of art by Laura Elenes (d. 2005) that addresses the burning of codices. Sylvia Elenes, the daughter, has given us permission to use this image in curricular materials.

Another image of burning codices, “Auto de fe de Maní,” a work of art by Carlos Andújar Domingo. See his webpage and this site where he explains his work, including another scene of the encounter.

Above is another work of art that treats the theme of the burning of codices. This bonfire takes place in front of the Maní church in the Yucatan, where Diego de Landa burned manuscripts on July 12, 1562, according to his own accounts. It was an act that greatly upset the Maya. Twenty-seven rolled manuscripts (i.e. screenfolds?) burned on that day.

Here is a link to another work of art, by Leonardo Paz, which also treats the Landa act.

Some zealous Spanish invaders, especially some of the friars, were nervous about what the pre-Columbian codices might have contained, worrying that their creation was the work of the “devil.” As a consequence, they burned many manuscripts, as depicted in a mural you might see in Patzcuaro, Michoacán, showing codices going up in flames. Other friars, however, actually helped indigenous elders get their stories told and recorded, even if the ecclesiastics had the goal or rooting out older beliefs and substituting them with Christianity.

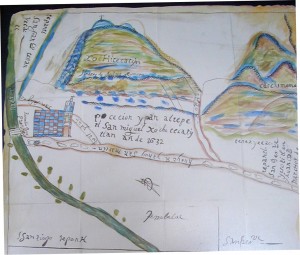

Detail of a map of Xochitecatzin, state of Tlaxcala, made in 1632. Reproduction in the Xochitecatl museum. (S. Wood, 2003)

Above, we see a pictorial manuscript or map, where we still see writing in Nahuatl and footprints on the roads (a prehispanic iconographic detail), although many other details show European influences. As the European presence increased and land-grabbing picked up pace in the seventeenth century, indigenous-authored pictorial manuscripts and maps increased in number again and tended to emphasize Native community antiquity, sound leadership, and the extensions of their territories, essential for their defense.

Explanation in Spanish about the various colonial manuscripts (called códices, mapas, and lienzos, among other names) painted in indigenous communities in defense of their antiquity and their territories. Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca, Santo Domingo Cultural Center. (S. Wood, 2009)

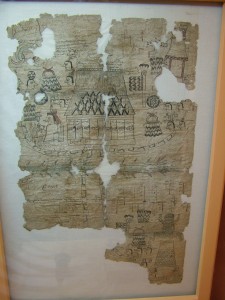

Possible Sixteenth-Century Pictorial

The Rufino Tamayo museum has on its walls what it calls a sixteenth-century plano (map). No further information is given as to its origin or its interpretation. To our knowledge, it is not published. None of the local scholars we have asked know anything about it. Click here to see an introductory analysis of some of its elements, by Stephanie Wood.

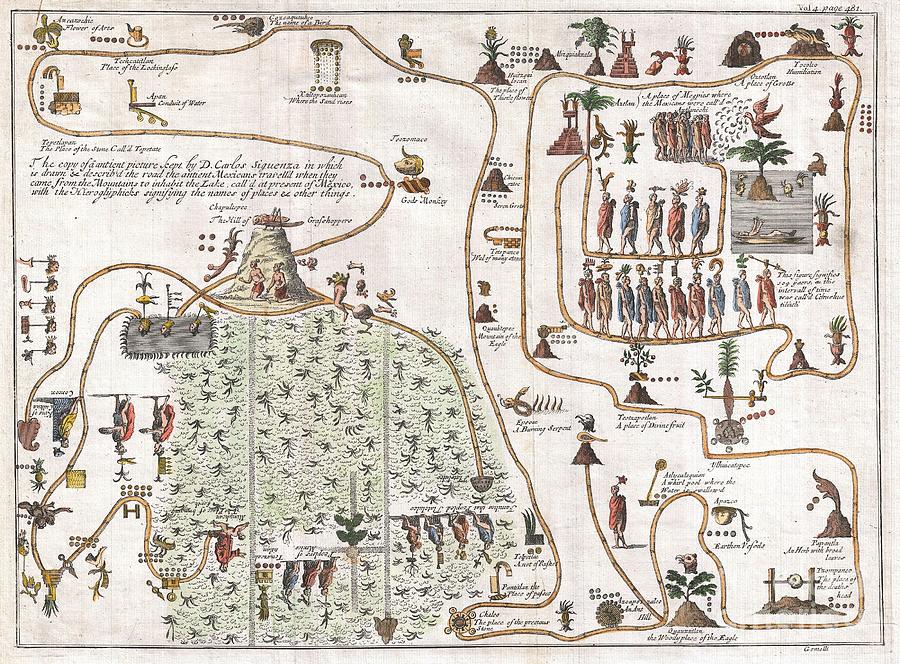

Legendary Migration from Aztlan

A number of pictorial manuscripts depict the legendary migration from Aztlan (a mythical origin site). One is this map drawn by Giuvanni Francesco Gemeli Careri in 1704, tracing the migration from Aztlan to Chapultepec (“Grasshopper Hill”), which is the site of a major park in Mexico City today:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gemelli_Careri_Aztec_Map.jpg

Gemelli map of the migration from the legendary Aztlan to what became Mexico City. 1704. Public domain image.

This map, while created by an Italian, is said to have been based upon an indigenous-authored manuscript in the possession of don Carlos Sigüenza (which is called the Mapa de Sigüenza). Gemelli tried to preserve glyphs, as much as possible, and reproduces corresponding glosses in Nahuatl, with English translations. Note the grasshopper on top of the hill just left of center.

For a discussion of some of the details of both the Gemelli and Sigüenza maps see: “Imagining the Conquest of Mexico,” a lecture by Professor Kevin Terraciano of UCLA, speaking at the Getty Research Institute (97-minute video on YouTube), from March 12, 2014, given in conjunction with an exhibition, “Connecting Seas: A Visual History of Discoveries and Encounters,” which examines sixteenth-century New Spain (early Mexico) and the nineteenth-century Belgian Congo. Terraciano also discusses other migration manuscripts, such as the Codex Boturini.

Analytical Studies of Codices/Pictorials and their Details

- Mesolore is an outstanding research website created by Liza Bakewell and Byron Hamann that aims to make codices accessible for teaching. It features interactive manuscripts from central Mexico and Oaxaca.

- Check out this wonderful geographical locator for the details of the conquests of the Codex Mendoza.

- Content from the Florentine Codex has been made into a children’s book, De lo que contaron al fraile, by Krystyna Libura, Claudia Burr, and Ma. Cristina Urrutia (Mexico City, 1994). We have made an adaptation of this book in English and with different images (some from the Codex Mendoza), available in a PowerPoint that can be downloaded and modified, expanding it or putting it into Spanish).

- The Mapas Project offers additional interactive representations of pictorial Mesoamerican manuscripts.

- Barbara Mundy, an expert in analyzing maps of New Spain, has developed an interactive, open-source, version of the Map of Zempoala of 1577, which was authored by an indigenous painter.

- More digital reproductions of Aztec codices from German scholars, hosted at FAMSI (some with commentaries in German, French, and Italian).

- The World Digital Library has a facsimile copy of the sixteenth-century Nahua codex, the Matrícula de Tributos (“Tribute Roll“), with zoomability.

- The Codex Mendoza (with includes the Matrícula and more) can be accessed through an English or a Spanish interface.

- The British Museum offers the Codex Aubin in full color images, and allows reproduction for use in teaching (although not for publication without permission).

- Tulane’s library, in addition to contributing incunabula to Primeros Libros, also hosts a digital collection of 17 Mesoamerican Painted Manuscripts (ca. 1500 to 1700 C.E.) that includes works on amatl, linen, and European paper, and representing Oaxacan genealogies (Mixtec) and central Mexican historical accounts, migrations, land disputes, land grants, censuses, and tributes. Images are in color and can be downloaded for independent study.

- Maya codices with notes by Randa Marhenke, hosted by FAMSI.

- Mixtec group and Borgia group codices with introduction by John Pohl, hosted by FAMSI.

- Edgar Anderson and John Jay Finan, “Maize in the Yanhuitlan Codex,” Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 32:3 (1945), 361–368.

- Bas van Doesburg: free, full-text article in Spanish about the sixteenth century in the lienzos of Coixtlahuaca, published in 2003

IAGO Free Library

The Instituto de Artes Gráficos de Oaxaca offers a free library where you can consult many facsimiles of codices. There are many shelves full of them.

YouTube Videos about Codices and Pictorials

- The Mapa de Santa María Guelacé, a 15-minute documentary produced by Stephanie Wood and Gabriela Martínez and edited by Shuo Xo, about a seventeenth-century pictorial map from a community in the Valley of Oaxaca struggling to defend its territory. 2015.

- Trailer for what will be a longer documentary about manuscript rescue and archives, by Gabriela Martínez: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E40gtR_XJdc

- Códices (2’50″ Spanish; an overview of mss in the Museo Nacional de Antropología) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9R8cheZAKqQ

- ¿Cómo se leen los Códices? (1’47″ Spanish; a brief overview about the reading order of different types of codices; from INAHTV) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S6DxiYdvz1k

- Códice Mixteco Nuttall: Animales Prehispánicos (3′ 34″ opening text-based slides in Spanish; no narration; drawings are re-created from the codex emphasizing pre-Hispanic animals; not individually identified) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5byr5rGx7vY&feature=related

- Códice Florentino [Book 12, The Conquest] (5’11″ images with text in Spanish) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r64CApew5Zo&feature=related

- Amoxtli “Libro de Anahuac,” “Codices de Anahuac” (3′ 06″ Spanish), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UU61pR3qhDo&feature=fvsr

- INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia) TV, short pieces about códices:

- Full play list: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrCDRHBaJg-SDyoazg5MKTc1phzMGpBA7

- Glimpses of the Códice Santa Cruz Tlamapa (present-day State of Mexico), about indigenous community tributes, 40 seconds (INAH TV)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8FP4tlKFz2Y - Glimpses of the Códice “Chavero” (about Huexotzinco), indigenous community tribute issues, about 40 seconds, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E4-GNrMbmCY

- Glimpses of the Mapa de Sigüenza, about the legendary migration that resulted in the founding of the capital of the Aztecs, about 40 seconds https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CrDhTutpyIs&index=18&list=PLrCDRHBaJg-SDyoazg5MKTc1phzMGpBA7

- “Restaura INAH códice colonial sobre tributos” (Atlapulco, modern State of Mexico, late seventeenth or early eighteenth century)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ge4P9JlZP0U

Curricula

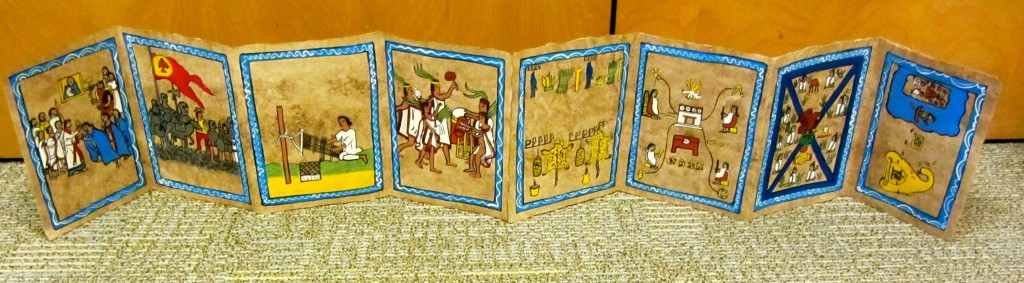

- Stephanie Wood’s screenfold codex exercise, intended for art and history classes (featured in the image above)

- Stephanie Wood’s adaptation of Marc Zender’s exercise for reading Mayan glyphs, with guidelines and answers [PDF].

- Stephanie Wood’s exercise for learning to read Nahuatl syllabic glyphs for placenames [PDF].

- Stephanie Wood’s exercise for learning to read Nahuatl counting symbols [PDF].

- Stephanie Wood’s exercise on Nahuatl that entered Spanish and additional loans that went from Spanish to English [PDF].

- Magliabechiano Codex, excerpts by Stephanie Wood: Nahua Calendrical Day Signs

- Celeste Williams’ My Mayan Codex, a lesson from 2010 [PDFs: 1, 2].

- Emily Ekstrand, a codex history lesson from 2010

- Lesson Plans (DOC; will download automatically)

- Codex Assignment (DOC; will download automatically)

- Mixtec Codex Elements (DOC; will download automatically)

- Student Work Sample (PDF; will open in browser window)

- Esther Jacob, Cómo leer un códice (Mexico: Editorial Trillas, 1999) [PDF].

- EDSITEment! (NEH) offers a lesson plan that could be adapted, adding a focus on the Codex Mendoza’s image of the founding of the capital city, Mexico-Tenochtitlan — Aztecs Find a Home: The Eagle Has Landed, http://edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/aztecs-find-home-eagle-has-landed; see key images of the Codex Mendoza at this University of Arizona library webpage.

- Another site that could benefit from a close look at a codex that shows the migration from Aztlan to what became Mexico City is Mesolore’s video of Davíd Carrasco providing an Introduction to Mesoamerica. The Codex Azcatitlan shows this migration; find images of it at this University of Arizona library webpage.

- We have one social studies and world history curricular unit from 2011, made by Josh Fitzgerald and Greg Gidden, “Introducing Mixtec Propaganda and History: Mesoamerican Pictographic Manuscript Reading and Analysis Curriculum.” This is designed for grades 11 through 12. (2010)

- Unit Information (DOC)

- Sources and Vocabulary (DOC)

- Exercises and Worksheets (DOC)

- Presentation (PPT)

- Michael Guenza, “Modes of Knowing, Means of Showing: Narrative Iconography in Ancient and Modern Times,” a high school art lesson from 2010

- In 2010 we distributed screen-folded amatl and asked art teachers to come up with ideas for students. Art teacher Pearl Lau made a “codex” that told the story of an adventure experience by two teachers who missed the bus on one of our excursion days.

- Maureen Yoder, elementary art lesson, “Maize Codex” (2011)

- Nicole Caracciolo and Angela Guy, “Codices Lesson“

- High school art teacher Angela Guy has shared the result of her students’ codex projects.

- From high school Spanish teacher Lynn Fernández (2010):

- Los jeroglíficos y códices (PPT, PDF)

- Codex Selden pages with questions (PDF)

- A middle school teacher (Stacy Greer), who was not in our program, but who worked with the University of California, Davis, to produce curriculum, has shared her unit, “Aztec Life as Revealed in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis,” c. 1563

- Here’s another teacher (Mike Reed) who was not in our program, but posted on Facebook a project he did with his students relating to the Popol Vuh creation story from the Quiché Maya

- Jessica Klonsky, “Pre-colonial Mesoamerican Writing (Latino and Latin American Literature, 11th grade, 2011)

- Unit Information (DOC)

- Is This Writing? (PPT)

- Pre-colonial Mesoamerican Writing Systems (PPT)

Additional Recommended Readings

- Sources and Methods for the Study of Postcontact Mesoamerican Ethnohistory, ed. James Lockhart, Lisa Sousa, and Stephanie wood (2007, 2010) [PDF];

- Joseph W. Whitecotton, Zapotec Elite Ethnohistory: Pictorial Genealogies from Eastern Oaxaca (1990) (we still need to determine chapters or pages);

- John Chance, “Colonial Ethnohistory of Oaxaca” in Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 4, Ronald Spores, ed. (1986), 165–189;

- remaining chapters of Mesoamerican Voices: Native-Language Writings from Colonial Mexico, Oaxaca, Yucatan, and Guatemala; “Lenguas y Escrituras de Mesoamérica,” Edición Especial, Arqueología Mexicana, 12:70 (2004);

- the remainder of Kevin Terraciano, The Mixtecs of Colonial Oaxaca (2001);

- María Teresa Sepúlveda y Herrera, Códice de Yanhuitlán (1994);

- the remainder of the Códice de Yanhuitlán, Introducción de Wigberto Jiménez Moreno y Salvador Mateos Higuera (1940);

- see this video, “Biblioteca Francisco de Burgoa,” (in Spanish, but worth viewing even if you do not understand the narrative; 10+ minutes);

- Robert T. Jiménez, “Mesoamerican Literacies: Indigenous Writing Systems and Contemporary Possibilities,” Reading Research Quarterly 43:1 (Jan-Mar 2008), 28–46 [PDF].

Additional Recommended Resources

Please see our Readings page for resources that have to be password protected for copyright reasons, as well as our Lienzos Today page, which takes a look at the importance of codices for indigenous communities today, and our Paper page, which takes a brief look at the native paper upon which codices were often made. Our Writing/Language page may be helpful for understanding the development of writing and types of writing. Our Poetry and Prose page offers links to a variety of written production Our page about the excursion to the Burgoa Library is also relevant.