On this page we will be assembling materials that may be useful for the development of curricula relating to Mesoamerican calendars. The study of calendars provides a window onto indigenous conceptualizations of time and relationships between human beings and their surrounding environments, as they tried to manage life in synch with the changing seasons (almanacs are important for agricultural practices). It also intersects with studies of religion (such as beliefs about a possible apocalypse), music (which is also closely linked to religion), medicine (health and curing), mathematics (measurements, cycles, astronomy, geometry, and so on), and genealogy.

Nahua Region

- Xiuhpohualli, 365-day solar calendar explained in Wikipedia; 20 x 18 (+5)

- Tonalpohualli, 260-day lunar/sacred calendar explained in Wikipedia; 20 x 13

- 52-year cycle = when xiuhpohualli and tonalpohualli calendars coincide, and then a new cycle begins

- Mesolore tutorial, “The Calendar Stone“

- Mesolore tutorial, “The Ritual Calendar“

- Mesolore tutorial, “The Solar Calendar“

- Mesolore tutorial, “The 52-Year Cycle“

- Mesolore tutorial, “The Ages of Creation“

- Mesolore tutorial, “Secret Names?“

- Mesolore tutorial, “Numeration“

- Mesolore bibliography relating to the calendars

- Mexicolore offers a good introductory page on “Aztec Calendar(s)“

- Khristiaan Villela, “The Aztec Calendar Stone or Sun Stone” (Mexicolore)

- Gianluca D’Andrea, “Creating a Sunstone Model” (Mexicolore)

- Ian Mursell, “Daysign Destinies!” (Mexicolore) — the idea here is to help young people feel a personal connection with the “Aztec” calendar while also coming to understand how an individual’s destiny might have been connected to the calendar and predictions about given dates

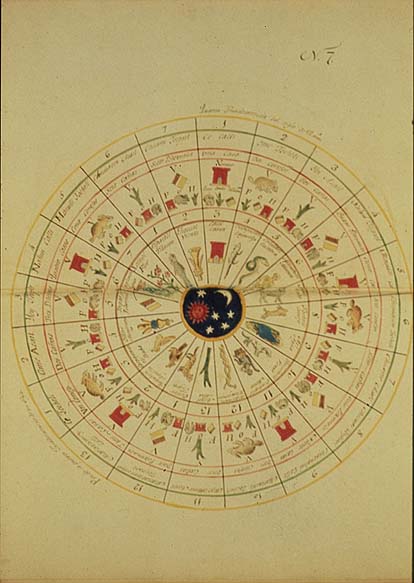

- Tonalpohualli, manuscript at the Library of Congress; “tonalpohualli,” refers to the Nahua sacred calendar, which ruled the life of each Mexica and was consulted on all important occasions. It was made up of 260 days, or 20 months of 13 days. The inner portions of this calendar represent the symbols for the 20 days and the sun, moon, and stars.

A copy of a rendering of the tonalpohualli. Library of Congress. Public domain.

Oaxaca Region

The longevity of indigenous calendars in the Oaxaca region is truly impressive. In the middle of the Spanish colonial period, in 1705 and 1705, some 106 separate calendrical texts and four collections of ritual songs were collected by ecclesiastics who were concerned with continuing pre-Columbian religious and philosophical beliefs. Professor Davíd Tavárez of Vassar College is one of the experts in the study of these manuscripts, many of which have texts in the Sierra Zapotec language.

- Davíd Tavárez and John Justeson, “Eclipse Records in a Corpus of Colonial Zapotec 260-Day Calendars,” originally published in Ancient Mesoamerica (2009), and available for free download through Academia.edu

- John Justeson and Davíd Tavárez, “The Correlation between the Northern Colonial Zapotec and Gregorian Calendars,” and 81-page full text chapter hosted on Professor Tavárez’s website at Vassar College

Zapotec Days Signs (image from Internet; must get permission)

The Borgia manuscript group (Mixtec) emphasizes divinatory calendars. See a sample page below, hosted by FAMSI, and for use in teaching by citing the source.

Page from the Borgia Codex (Mixtec) with information about the tonalpohualli. Hosted by FAMSI. Okay to use in teaching with proper citation of John Pohl’s Mesoamerica and FAMSI.

Maya Region

The year 2012 and the supposed Maya belief in apocalypse received a lot of popular attention. Scholars had to work hard to dispel the sensationalism that the media whipped up around the globe in association with 2012.

- Haab, the Maya equivalent of the Xiuhpohualli, also called the civil calendar, 365-day calendar, and the one that was used with the “Long Count” — explained by Christopher Minster, “The Maya Calendar“

- Tzolk’in, the Maya equivalent of the Tonalpohualli, the 260-day lunar/sacred calendar (Wikipedia)

- Carlos Barrera Atuesta, “How to Predict Astronomical Events Based on the Tzolk’in Calendar” (Academia.edu)

- Audio interview with Professors Matthew Restall and Amara Solari (Penn State), “2012 and the End of the World,” introducing their book about the topic

- Johnathan Reyman, “The End of Time: Maya, Aztec, and Hopi Views of the ‘End of the World‘” (Mexicolore)

- William Morris, “Welcome to a New Maya ‘Long Count’” (Mexicolore)

- “Calendrics,” a general introduction, hosted by FAMSI; see the bottom of the page for links to more resources

- Mark Van Stone, “It’s Not the End of the World: What the Ancient Maya Tell Us About 2012,” hosted by FAMSI

- David Bolles, “The Mayan Calendar, The Solar – Agricultural Year, and Correlation Questions,” hosted by FAMSI, originally published in Mexicon, September 1990; also available in PDF

- Princeton hosts an image of a “brujo” (Spanish for warlock) calendar of K’eq’chi Maya origin, possibly colonial or nineteenth-century; lines of music also appear in association with the “lucky” and “unlucky” days of this calendar

- Princeton also hosts the facsimile of two sacred Yucatec Maya books of Chilam Balam, from Chumayel and Kaua, which have many calendrical elements, divinatory and almanac-type information. We also see information about births and deaths in the Na family (genealogy), and some information about medicine. These copies date from the nineteenth century, probably stemming from older manuscripts. But the longevity of this type of information and the use of Native calendars is impressive.

- FAMSI offers a facsimile of the “Calendario de los indios de Guatemala, 1685, Cakchiquel” — another notable example of the longevity of indigenous calendars.

- Video lecture, “Año 2012 en el calendario maya,” hosted by Universidad Francisco Marroquín, Guatemala, by David Stuart, 1 hour and 15 minutes, 2012

- Video lecture, “El tiempo infinito de los mayas,” hosted by Universidad Francisco Marroquín, Guatemala, by Oswaldo Chinchilla, 13 minutes, 2012