Cacti in Mesoamerican Cultures

Mexicolore’s article “Cactus” (Renee McGarry) illustrates her short article with images of pre-Columbian artifacts and from manuscripts, emphasizing cacti in Nahua culture.

The biznaga cactus (from huitznahuatl, a Nahuatl term) is endemic to Mexico. It can get quite tall, taller than a person, and it is very round and bulbous. Humans and other animals will eat this cactus. It is in danger of extinction.

A number of fascinating cacti can be found in the ethnobotanical garden, including an evolutionary early tree/cactus (peresquia lichindiflora) with both spines and leaves. The cactus later evolved into a leafless plant in order to conserve water and protect itself.

On the maguey agave and the mezcal beverage made from it, please go to our excursion page for Mitla and scroll to the bottom.

Maguey hearts (piñas) being taken to be crushed for making mezcal. Photographer unknown. Somewhere in the state of Oaxaca, ca. 1930s. WHP collections.

Pińas (maguey hearts) left over from the mezcal festival in the Llano park, July 2014. (Photo, S. Wood)

Nopalli as Food

The nopal cactus leaves can be scraped of their thorns, chopped, steamed, and eaten. The cactus fruits, which come in a number of colors, can also be peeled and eaten.

An appliqué piece from San Francisco Tanivet, Oaxaca, showing a woman harvesting the “tunas” (fruits) of the nopal. (Photo, R. Haskett, 2014)

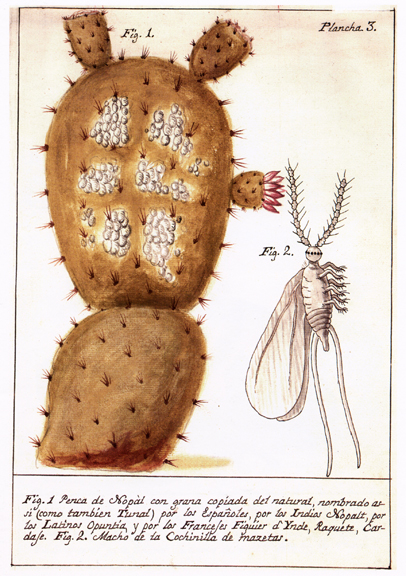

Nopalli & Cochineal

The nopal (Spanish term, from nopalli in Nahuatl), or prickly pear cactus, has been a source of food for indigenous people across Mesoamerica since pre-Columbian times. The tender, newer pencas (branches or leaves) are scraped to remove the thorns, then diced, and cooked. The nopal will also bear edible fruit, called tunas in Spanish, that come in red, green, and white. A nopal with tunas appears on the amate painting that we have animated.

The red dye, cochineal (cochinilla, in Spanish) comes from a beetle that grows on the nopal cactus. It was a dye that was developed in pre-Columbian times and continues to be a product used in dying many products today, including Oaxacan textiles.

Rancho La Nopalera, home of Tlapanochestli products made from cochineal, is a site we will visit. Below are some photos taken at the ranch.

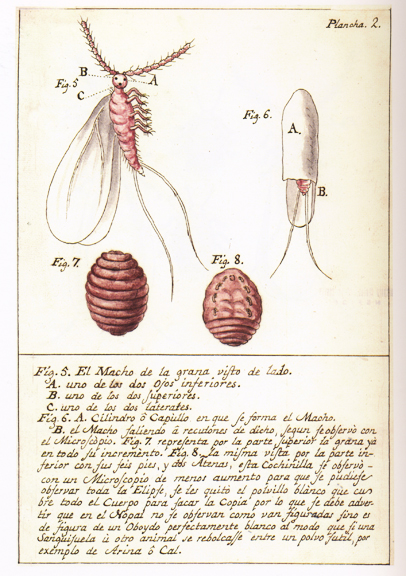

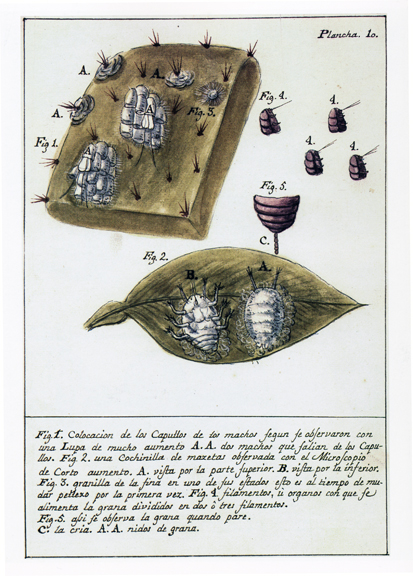

Eighteenth-Century Study of Cochineal

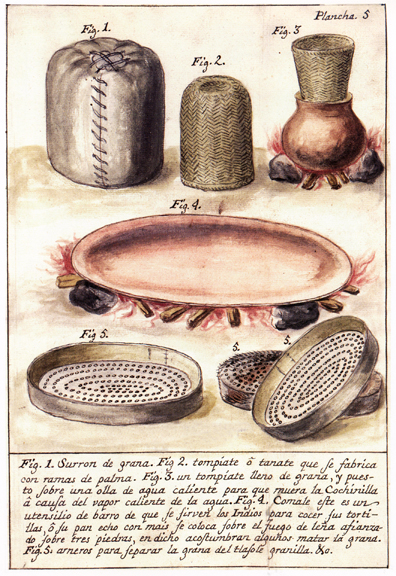

Don Joseph Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez created a manuscript volume about the dye, “grana cochinilla,” in Mexico City in 1777. A facsimile has been published by Carlos Sánchez Silva and Alejandro de Avila Blomberg, La grana y el nopal en los textos de Alzate (Mexico: CONACULTA, AGN, and Arte Popular de México, 2005). Below are the illustrations that accompanied the long and text in Spanish.

Cochineal insects drying on a petate in the sun, and a jug where insects are placed, inside another jug with hot water, so that the insects will die.

A bundles of cochineal; a basket for killing cochineal over a boiling vessel (tompiatl is a Nahuatl word); a comal, upon which some people kill the insects; and winnowing containers.

An indigenous laborer using a deer’s tail to brush the insects from the nopal into a container (xicalpestle, a Hispanized Nahuatl word).

A steam bath (temazcalli, in Nahuatl) where people would bathe but where some would also kill the cochineal insects.

Cochineal Harvesting, Mural by Arturo García Bustos

In the detail of a scene in the mural in the municipal palace, we see a woman using a brush to remove the cochineal from the nopal. She carries containers for collecting the scrapings.

Cochineal Display in Museum, Santo Domingo

According to the museum sign, the “grana cochinilla” is an animal-based dye used since prehispanic times in indigenous religious activities. Its commercial importance grew at the end of the sixteenth century as industrial textile production expanded in Europe and the demand for dyes (especially red dye) increased dramatically. Oaxaca, at that time, was the world’s dominant producer of cochineal. The dye was sent to other parts of New Spain and to the port of Veracruz for exportation to Europe. Oaxaca lost its monopoly over cochineal in the nineteenth century owing to competition with other countries and because of the discovery of artificial dyes in Germany around 1860.

IAGO Free Library

The Instituto de Artes Gráficos de Oaxaca (IAGO), on Macedonio Alcalá (across and a bit north of Santo Domingo), has a free library that you can use to pursue this topic. Here is one book in their collection about the meaning of colors and how colors are made.

Anne Varichon’s book about the meaning of colors and how they are made. At the IAGO library, where you can consult it freely.

Videos of Possible Interest (YouTube)

- “Museo Grana Cochinilla ‘Santa Lucía del Camino, Oaxaca,’” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RdsVHdDZE7k (n.d., 2:43) — this is a slide show to music and the titles are in Spanish, but it highlights the sustainable cultivation of nocheztli (cochineal) and its uses

- Here’s a short video with a focus on the cochineal farm we will visit (in Spanish): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hdQk6J_tzd8;

- Natural dyes in Oaxacan huipiles: ”Tres Colores: Indigo, Cochineal, Caracol,” (images and music, with fabrics identified by town; no other explanations) (2011, 3:12), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-cWTrNrWM58;

- Video playlist of the Tlapanochestli Cochineal Farm taken by Vinny Civarelli Jr.

Curricula from Past NEH Summer Institutes (extend, revise, or mine ideas for your own unit)

Stephanie Tietz, high school science unit, “Incorporating Mesoamerican Content Into the Biology Curriculum” (2010)

- Lesson Plans (DOC)

- “Cochineal: The Red Gold of the Mixtec” (PPTX)

Nancy Tran Le, high school science unit, “Cochineal Dye Chemistry” (2011)

- Unit Information (DOC)

- Video Demonstration (M4V)

Additional Resources

According to Nestlé Brand Ambassador Jennie Powell, here is a list of Nestlé products that contain Cochineal dye.

Please also see our pages about the excursion to the Rancho La Nopalera and the excursion to Mitla, when we will stop at Rancho Zapata, the mezcal distillery and restaurant.