On this page we are assembling material that might be helpful for developing curricula relating to pre-Columbian religions and how the introduction of Christianity was mediated by indigenous peoples. Since this page is under construction, it might be best not to print it until closer to the start of the Institute.

Mesoamerican Religions

Each Mesoamerican culture had its own unique beliefs and practices, probably even varying from community to community somewhat. But there were also shared characteristics in the religions held by cultures across the vast region. Wikipedia offers a brief introduction to Mesoamerican religions, focusing on cosmology, or the way the world, the underworld, and the heavens (including the stars and planets) were conceived, and the place of deities and humans within those realms. Mesoamerican mythology and religions, in Wikipedia, also indexes related web pages relating to the broader theme.

The plumed or feather serpent, which linked the earth and the heavens by being able to move on land and in the air, is a recurring divinity in Mesoamerica, across the region, and across time, from the Pre-Classic to the Post-Classic periods. Wikipedia gives this deity some individual attention, along with the more specific deity of Quetzalcoatl of the Nahuas. Teotihuacan had a temple devoted to the plumed serpent. Under this temple, dozens of gold-like orbs were discovered recently.

Ritual

The term “ritual” does not exist, per se, in indigenous languages of Mesoamerica. A digital “learning object” hosted by Wesleyan University explores the nature and meaning of rituals, striving to understand indigenous points of view. See “Unaahil B’aak: The Temples of Palenque” three-page section on ritual for interesting findings that explore codices, paintings on pottery, stone carvings, modern-day Lacandón chanting, and more.

Pre-Columbian Sacrifice

The topic of human sacrifice, especially as practiced in prehispanic times, requires sensitivity to avoid sensationalizing and misrepresenting it. But some form of sacrifice was practiced by most Mesoamerican cultures prior to (and after) European colonization. Most sacrificial forms after colonization involved animals. Archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence clearly points to examples of human sacrifice across Mesoamerica. Many scholars believe that sacrifices were connected to a desire for continued fertility (agricultural productivity, human fertility), and that the role of deities was also signifcant. Some believe blood spilled through sacrifices represented a refresher for the earth. Some see it as a thank-you to the deities for the existence of life.

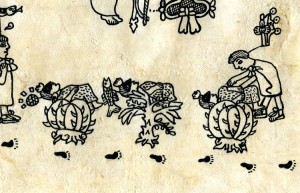

The sacrifice of humans bent backwards over the biznaga (barrel cactus) in the Codex Boturini. From Mexicolore.

Dr. Elizabeth Graham, Senior Lecturer in the Archaeology of Latin America, Institute of Archaeology, University College London, has tried to put “human sacrifice” into a modern perspective, debunking it to some extent. There are proponents of all sides of this history — from a belief in zero sacrifices to exaggerated numbers of sacrifices. Graham’s approach is not without strong reactions from readers, but her effort to put the topic in a perspective that compares it to the loss of life in modern wars is worth considering. See her article in Mexicolore, “There is No Such Thing as ‘Human Sacrifice,'” as well as some of the comments that follow.

Detail of the Codex Laud, representing human sacrifice. Bodleian Library, Oxford. Thanks to Mexicolore.

Another effort to debunk the Western view of the Aztecs as barbarians (connected with sacrifice), also appears in Mexicolore’s answers to the question, “Were the Aztecs as Barbaric as Described by the Spaniards?” This was also the opinion of Jacques Soustelle, “Clearly, it is difficult for us to come to a true understanding of what human sacrifice meant to the sixteenth century Aztec; but it may be observed that every culture possesses its own idea of what is and what is not cruel. At the height of their career the Romans shed more blood in their circuses and for their amusement than ever the Aztecs did before their idols. The Spaniards so sincerely moved by the cruelty of the native priests, nevertheless massacred, burnt, mutilated and tortured with a perfectly clear conscience. We, who shudder at the tales of the bloody rites of ancient Mexico, have seen with our own eyes and in our days civilized nations proceed systematically to the extermination of millions of human beings and to the perfection of weapons capable of annihilating in one second a hundred [times] more victims than the Aztecs ever sacrificed.’ Jacques Soustelle quoted by Gertrude Kurath and Samuel Martí in their book Dances of Anáhuac.

Mexican novelist and cultural commentator, Octavio Paz, had this to say about sacrifice: [The Aztecs were] a “people of soldiers and priests, stargazers and sacrificers. And of poets: that world of brilliant colours and shadowy passions was interspersed with brief, prodigious flashes of poetry. And in all the manifestations of that extraordinary and terrible nation, from astronomical myths to poets’ metaphors, and from daily rituals to priests’ meditations, the obsession, the smell, the stench of blood. Like those torture wheels that feature in the novels of de Sade, the Aztec year was a cycle of 18 months drenched in blood; 18 ceremonies, 18 (different) ways to die: from shooting with arrows to drowning, from strangling to skinning. Dance and penitence….”

From his book Labyrinth of Solitude, Postdata.

Mexicolore also offers an explanation that suggests numbers associated with sacrifice have been exaggerated. See Spanish scholar Juan José Batalla’s bilingual short statement on the topic. This scholar does support the interpretation that Nahuas/Aztecs made sacrifices “in honour of their gods.” Mexican scholar Cecilia Rossell agrees, seeing the spilling of blood as a gift to the gods.

Mexicolore also has a short piece by a renowned scholar who is asked to consider whether human sacrifices ever involved extracting the liver. What happened to the head and heart (the most prized parts extracted during a human sacrifice) is discussed in this Q & A.

It is important to recognize that individuals in multiple Mesoamerican cultures sacrificed their own blood, through blood-letting, often called self-sacrifice or auto-sacrifice, to “refresh and give thanks to the earth.” See “Ritual Self-(Auto)Sacrifice,” in Mexicolore. Take a close look at the images from the codices.

Monte Albán Classic-Period stone carvings of figures whose genitals may have been cut for blood letting or perhaps as part of a sacrifice of war captives. Monte Albán museum. (Photo, R. Haskett, 2011)

Introduction of Christianity

A bibliography on the introduction of Christianity would be very lengthy. Looking for free, full-text treatments of the subject, we find, for example, Garry Sparks’ downloadable syllabus for his course, “Missionaries and Mesoamericans in the 16h Century,” posted by the author to Academia.edu, which might be helpful in our endeavor to design curriculum. One thing to bear in mind, however, is that the term “missionary” as many of us know it in the U.S. — connected with frontier institutions and situations — did not fit the Mesoamerican scene, for the most part. Mesoamericans, in large part, were sedentary peoples with organized religions, priests, temples, and well established practices. The imposition of Christianity was almost layered on top of what existed, with long-term efforts to encourage indigenous people to give up most of their prehispanic beliefs and practices. They might become baptized in large numbers, but true or even partial conversion took a very long time. In remote communities, it could be rather unsuccessful, allowing for unique, indigenous Christian forms to flourish.

The painting of the baptism of the four most important indigenous nobles in Tlaxcala in the sixteenth century, includes Xicotencatl. Standing watch are Cortés and his famous indigenous interpreter, Malintzin. The baptism of these Tlaxcalan figures was recalled for its powerful symbolism — if the leaders accepted the new faith, it was a model for commoners to step up for baptism, too. It is worth remembering that Tlaxcalan allies helped the Spaniards defeat the Aztec empire, and their alliance was rewarded. But, by the late seventeenth century, it may have behooved the church to inject this memory into what was seen as a lagging progress toward full conversion by the indigenous people. “Idolatry” campaigns periodically swept Mesoamerica in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in an effort to wipe out prehispanic beliefs and practices, which nevertheless continued, especially in remote communities.

Even in indigenous-authored manuscripts, such as the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, the memory of alliance with the Spanish and the willing acceptance of the Christian faith is memorialized, as we see below in this reproduction of a page of the manuscript.

The encounter of Spaniards and indigenous nobles in Tlaxcala, according to the Lienzo de Tlaxcala. Note the large Christian cross. Photographed from the facsimile in the library of the Fundación Bustamante, Oaxaca. (R. Haskett, 2009)

Santiago Matamoros

The men on the conquering expeditions came to Mesoamerica with a wealth of experience that was relevant to the way they approached the introduction of Christianity — experience that came from the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslims, from efforts to settle the Atlantic Islands, and from initial conquering efforts in the Caribbean. Their patron saint was still Santiago Matamoros (Moor-Killer). For further examples, see our page on the Spanish Conquest.

Santiago Matamoros relief from New York, on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (R. Haskett, 2011)

Ironically, although St. James symbolized the Spanish conquest of Mesoamerica, indigenous communities embraced the saint as a figure who could protect them against enemies, who could help ensure agricultural fertility, and even as a figure who could help heal people. The horse, which had once existed in this hemisphere, died out, and been reintroduced by the Spaniards, was also an object of great interest. Frightening at first, the horse quickly became coveted by indigenous lords, who applied for licenses to ride. The white horse of Santiago, according to the exhibit curator, was perceived by indigenous people as the embodiment of divine will.

Songs

Pre-Columbian Nahua songs, at least as they survived a century after European contact, retain a distinctly indigenous flavor even as they also refer to the Spanish invasion and seizure of power and incorporate Christian religious influences. For a free, online English translation of Nahuatl-language songs by John Carl, visit FAMSI’s site, “The Flower Songs of Nezahualcoyotl: Ancient Nahuatl (Aztec) Poetry.” This material may or may not have been sung in what is now the state of Oaxaca, but we do know that Nahuas settled in Oaxaca.

The Dominicans

It was the Dominican order of the Catholic faith that played the most prominent role in Christianizing the people of Oaxaca. The Dominicans were just one of three prominent orders who were especially influential in the evangelization of Mesoamerica — the Franciscans and Augustinians were also present and influential early on. The Jesuit order, formed later, arrived on the scene to find that the other orders were already well entrenched.

Above you see a portrait of a Dominican friar made by an indigenous scribe in the manuscript now called the Yanhuitlán Codex. Native scribes often captured portraits of Spaniards seated in chairs and sitting at tables covered with manuscript pages, quills, and ink. They were fascinated with the new technology. They had their own paper and writing methods, but they also quickly took on European forms of painting and writing.

Architectural Innovations

Mockup of monastery and church with capillas abiertas and outdoor ceremonialism. Tlaxcala Memory Museum. (S. Wood, 2003)

Architecture provides a surprisingly fruitful approach to the topic of the introduction of Christianity in Mesoamerica. Many Christian churches were built on sites that were sacred in pre-Columbian communities. See, for example, the way this Catholic church sits in the middle of the ruins in the Zapotec community of Mitla. And see the facade and foundation of the church of the Zapotec community of Teotitlán del Valle, with their pre-Columbian stonework.

Why might the evangelizers have chosen to re-purpose sites of importance in prehispanic faith? Why would they be willing to display carved stones that could have a sacred meaning that fell outside of Christianity?

Example of continuing outdoor ceremonialism into the Spanish colonial period. Scene from a folding screen (biombo) at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art, c. 1690. (Photo, S. Wood, 2010)

In this scene of outdoor ceremonialism in the middle of the Spanish colonial period, we see an example of an indigenous couple’s wedding (with marriage evident of the adoption of a Christian sacrament), possibly in Santa Anita Iztacalco. Part of the celebration includes a “flying pole,” where four men would originally have descended, spinning from the top platform, flying like birds, while a man stayed at the top playing a flute. This ritual originally connected with the four cardinal directions and the center of the Nahua universe. We also see the indigenous dancers doing a dance that was believed to have been practiced in Moctezuma’s time (and therefore probably prehispanic). The fact that it lives on, and is practiced at the time of a Christian wedding, is an example of indigenous Christianity.

Variations in Evangelical Methods

Description of a Burial of an Archbishop, Mexico City, in 1612

Religious “Paintings” in Feathers

An example of practices that allowed for indigenous ways to live on is found in the “paintings” (really mosaics) in feathers that represented a continuity in technique — while employing new religious motifs. Below we see an indigenous-authored work of feathers glued onto copper from seventeenth-century Puebla. It represents St. Francis before the Pope Inocencio III.

Syncretism

To follow the links to items highlighted in blue in the caption for this image, please go to the RMA, Red Mexicana de Arqueología.