Collectors and oni

Unlike foxes and tengu, oni have no intrinsic connection with the history of senjafuda. But the sheer frequency with which they occur as pictorial motifs in senjafuda ensures that at least some of their appearances will be self-referential. And indeed, there are several charming examples of oni interacting with senjafuda pasters or collectors, or with votive slips themselves.

The slips above depict, from left to right:

A set of matching-game cards pairing Oni with the name Ōta Setchō.

A fierce-looking oni biting down on an ema decorated like a senjafuda (with a daimei and a ren logo).

A thunder god on a cloud fishing for senjafuda.

Another example of the thunder god fishing motif. Here he has caught a bag of puffed rice snacks.

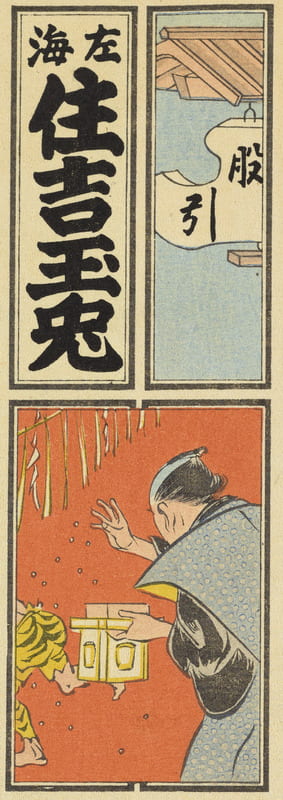

The first slip above represents the traditional spring ritual of scattering toasted beans to chase away demons. Here an actual oni is shown fleeing the beans.

On the second slip, instead of beans the oni is fleeing a shower of senjafuda—a nice contrast to the thunder god trying to catch senjafuda.

The third slip shows an oni fleeing senjafuda thrown by a girl instead of a man.

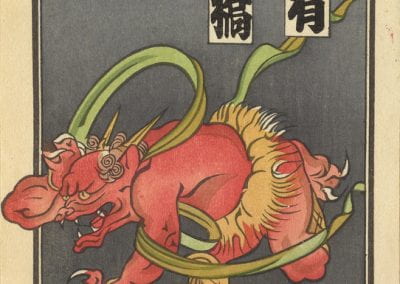

In light of the previous two examples, it seems likely that the oni on the fourth slip above is fleeing the daimei visible in the top right (which read “Starr” and “Maebashi”).

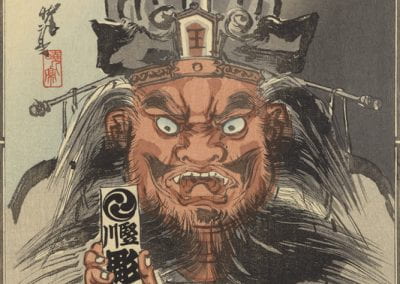

The last slip above is a large (8-chō) depiction of Enma, King of Hell, by famed Meiji-era artist Kawanabe Kyōsai. Instead of his characteristic flat scepter, Enma holds a senjafuda.

Pasting on Enma

Two types of oni interaction with senjafuda practitioners deserve special mention. One is how statues of oni—almost always Enma the King of Hell, actually—are depicted within senjafuda as targets of pasting activity. The act of pasting a slip on a statue would have been particularly appealing to some aficionados because of the daring and irreverence it required; celebrating (or imagining) it in a senjafuda was therefore a celebration of the peculiarly iconoclastic nature of senjafuda devotion.

The first slip above shows a statue of Enma with four senjafuda pasted to his chest. The composition emphasizes both the monumental size of the statue and the comical impudence of the pasters’ achievement.

The second slip represents a statue of Enma with a senjafuda pasted onto his nose. The miniature senjafuda pasted onto Enma’s nose is actually a separate piece of thin paper pasted onto the larger slip.

The third slip is a gargantuan 32-chō image of a statue of Enma festooned with senjafuda.

Oni In Hell

The other special type of oni interaction with senjafuda has to do with the oni’s role as tormentors in the Buddhist conception of hell. As we have seen, senjafuda were originally a form of worship, and therefore a tool of devotion. But since temples and shrines (and sometimes governmental authorities) frowned on them, they were also a form of transgressive play. This means that senjafuda practitioners were always conscious of being in an ambiguous relationship to organized religion, an ambiguity captured in the image of the tengu as well as in the depictions of King Enma defaced (literally in some cases) by senjafuda. Perhaps the ultimate expression of senjafuda self-consciousness comes in images of pasters being punished in hell for their activities. At least three versions of this theme may be found in the UO’s collection of senjafuda.

The most straightforward is this one, a scene of Enma judging sinners newly arrived in hell. In the top left corner the newly dead are relieved of their clothes by Datsueba (the Clothes-Stripping Crone) on the banks of the Sanzu River, which they must cross to enter the afterworld. In the middle of the image is Enma at his desk, reading from a scroll. At Enma’s shoulder is the grotesque Seeing Eye and Sniffing Nose, which help him discern people’s misdeeds. Assorted sinners and oni crowd the space in front of Enma’s desk, but the key to the image is the mirror on the left. Enma’s mirror displays to sinners the sins in life that they’ll be punished for in death. In this mirror we see senjafuda practitioners: one holding a pole-mounted brush, and another writing on a temple gate. The message is clear: these men are being punished for defacing temple property. But another message is equally clear: the people who commissioned this image are endlessly entertained by the prospect. This image’s combination of faith and irreverence perfectly encapsulates senjafuda culture.

A more elaborate treatment of the same motif can be found in the 24-chō horizontal composition below. It takes the form of a hell scroll, a common motif in medieval Buddhist art. This scroll is mounted on purple fabric. On the far right we can see the outer cover of the scroll, curling toward the viewer, with red cords peeking out from behind it. At far left is the inner section of the scroll, extra paper attached to a wooden rod around which the scroll is wrapped. Scrolls read from right to left, and when we view this one that way we can follow the progress of the newly dead through hell. First we see a milepost that says “Sanzu River,” and then we see sinners surrendering their clothes to Datsueba. After that is a small gap left by a missing panel, but the next panel shows the end of Enma’s desk and the Seeing Eye, allowing us to imagine the figure of Enma that’s missing. From there we follow the dead souls through various gory and horrific punishments at the hands of oni, all rendered in fantastic detail, until at the other end of the scroll we see the bodhisattva Jizō arriving to rescue the sinners. The final image is of the Buddha hovering above lotus blossoms, waiting to welcome the delivered souls of the dead—a happy ending, in other words.

The mirror by Enma’s desk doesn’t show the viewer what these sinners have done, but we can guess, particularly if we read the inscription at the beginning of the scroll. It informs us that this piece was designed as a tribute to three recently-deceased senjafuda practitioners. The composition thus allows the ren to imagine their deceased friends being appropriately punished for their hobby, but ultimately saved for their devotion. The result is a tour de force of senjafuda that’s both playful and deeply moving.

It’s a shame that the Starr collection is missing the slip showing Enma. But the Shōbundō collection contains a later set of senjafuda that reproduce this composition, allowing us to see what Enma would have looked like in this context (below). It also allows us to appreciate some of the differences in workmanship between earlier senjafuda (the Starr series is dated 1930) and later (the Shōbundō series is from circa 1965).