New Acquisition: Victoria Regia

The social structure of Victorian England represented a chasm deep and wide separating the public and private sphere, one that women were forced to straddle uncomfortably and fought to bridge and to bind seamlessly. The private sphere was considered the realm of women, and the public sphere the realm of men. A unification of the two was discouraged, if not entirely avoided and feared. Emerging feminist activists attempted to eradicate the divisive nature of Victorian England society by championing women’s suffrage and the right to education and employment. A particular feminist, Emily Faithfull, keenly and astutely estimated the impact of gainful, fitful employment for women in elevating their status (Frawley, 1998). A close cohort of Emily Faithfull, Emily Davies, denounced the common justification for the oppression of women that asserts women inherently different than men. Davies instead declared “a deep and broad basis of likeness” between men and women, and believed “only good could come of enabling women to take a greater part in the intellectual and public life of men” (Schwartz, 2011, p. 674).

Emily Faithfull’s greatest conquest involved shattering hegemonic expectations of the sexes and breaking women into a sphere of the working world traditionally relegated to men, expertly done so with the novel development of a printing press owned and operated by women. The birth of the historical Victoria Press was closely knit to the pioneering women of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women (SPEW), and to the women of the Langham Place Circle, an activist organization for the employment of women and a constituency of women editors and publishers of women’s periodicals. The women instrumental in the propagation of these activist organizations include Emily Faithfull, Jessie Boucherett, Bessie Rayner Parkes, and Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (Robinson, 1996). In regard to the guiding principles of the activism of SPEW, the Langham Place Circle, and the Victoria Press, founder Emily Faithfull poignantly stated,

Our cry is not for work per se, but for fit work fitly paid. Time will work great changes in our traditional and conventional ideas on these points; and the question has, I believe, to be wrought out, rather than thought out – it must be solved by actual progress, however slow, rather than by written arguments, however specious. (Frawley, 1998, p. 87)

The Victoria Press produced publications that were “Conducted by Women,” an inscription often used by publishers to delineate a publication as produced primarily by women. Bessie Rayner Parkes of the Victoria Press and Langham Place Circle consulted close friend George Eliot about the nature of publishing, especially in reference to women. George Eliot replied, “It is a doctrine of Mr. Lewes’s, which I think recommends itself to one’s reason, that every new or renovated periodical should have a specialité – do something not yet done, fill up a gap, and so give people a motive for taking it . . . ” (Robinson, 1996, p. 159). Emily Faithfull and her cohorts embodied the words of George Eliot deeply, constructing a business and creating a product innovative and that filled a gap – the absence of the voice and presence of women in publishing and in the larger public sphere.

The selection of “Victoria” as the representative name of the printing press, and the use of “Victoria” in the titles of The Victoria Magazine and Victoria Regia, was by far no haphazard, half-baked choice. Emily Faithfull and the Victoria Press held Queen Victoria in high esteem, regarding her as an exemplar in the struggle to maintain domain in both the private and the public spheres (Frawley, 1998). The Victoria Press’ use of Queen Victoria’s namesake and the selection of content in the publications attracted her interest and procured her support. Queen Victoria named Emily Faithfull as “Printer and Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty” (Frawley, 1998, p. 93).

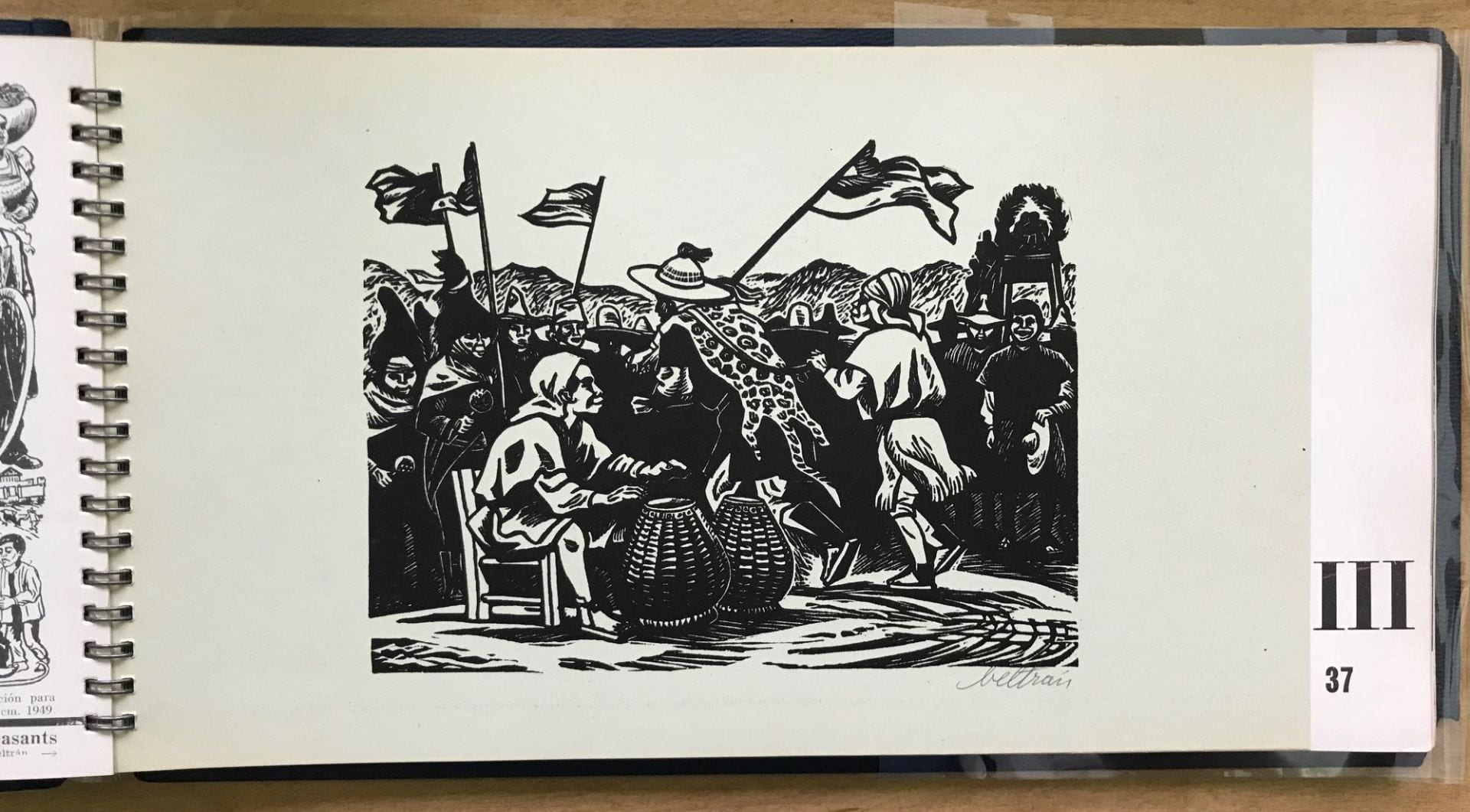

University of Oregon Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA) acquired one of the Victoria Press’s earliest publications, the Victoria Regia. The Victoria Regia: A Volume of Original Contributions in Poetry and Prose was edited by Adelaide A. Proctor, a fellow member of the Langham Place Circle (Tusan, 2000). The volume is a compilation of a variety of literary works in many forms contributed by women and men, arranged with no special or preferential consideration. In truth to the Victoria Press’ mission and values, the Victoria Regia contained a tribute to Queen Victoria in the preface that extolled the Queen and served as a nod of appreciation to her support (Frawley, 1998).

Emily Faithfull and her cohorts created something so pioneering, so magical and transformative. For many women, the Victoria Press helped connect the private and public spheres of their lives, allowing habitation and fulfillment in both realms. The Victoria Press was vastly influential in promoting gainful, fitful employment for women on a grander scale. The Victoria Regia and other early works of the Victoria Press laid brickwork for the continued success of the all-woman printing press.

Sources

Frawley, M. (1998). The editor as advocate: Emily Faithfull and “The Victoria Magazine.” Victorian Periodicals Review, 31(1), 87-104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20083055?seq=1

Robinson, S. C. (1996). “Amazed at our success”: The Langham Place Editors and the emergence of a feminist critical tradition. Victorian Periodicals Review, 29(2), 159-172. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20082917?seq=1

Schwartz, L. (2011). Feminist thinking on education in Victorian England. Oxford Review of Education, 37(5), 669-682. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23119462?seq=1

Tusan, M. E. (2000). ‘Not the ordinary Victorian charity’: The society for promoting the employment of women archive. History Workshop Journal, 49, 220-230. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4289669?seq=1

Written by Alexandra Mueller (Special Projects Archivist)