New Purchase: William Morris’ Kelmscott Press Romance Trilogy

Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA) recently purchased the English Arthurian romance trilogy printed by William Morris, the nineteenth-century British artist who was a central figure in the movement to return to the medieval and early Renaissance artistic ideals he felt had been abandoned by contemporary society. The three works are titled: The Romance of Syr Perecyvelle of Gales (1895), The Romance of Sir Degrevant (1896) and The Romance of Syr Ysambras (1897).

Morris was an ardent socialist and a central figure of the Arts and Crafts movement, which began in England as a reaction against the mechanized production of objects that was a hallmark of the Industrial Revolution and spread throughout much of the Western world. He believed in the ability of beautiful things to improve the human condition and that beautifully crafted objects should be accessible to all people. Morris insisted that all workers should take pride in craftsmanship. The revival of handpress printing using handset type based on fifteenth-century designs, handmade paper, and a lush style informed by medieval illuminated manuscripts was among Morris’s greatest contributions, and his work initiated the 20th-century revival of the book arts.

In 1844, James Orchard Halliwell edited this English medieval manuscript, which is held at the Library of Lincoln Cathedral (Cambridge) and published it as The Thornton Romances: The Early English Romances of Perceval, Isumbras, Eglamour, and Degravant (1844). The medieval manuscript was compiled and copied by the fifteenth-century English scribe and landowner Robert Thornton. The manuscript is notable for containing single versions of important poems such as the alliterative Morte Arthure and Sir Perceval of Galles and gives evidence of the complex literary culture of fifteenth-century England. The manuscript has three main sections: the first one contains mainly narrative poems (romances, for the most part); the second contains mainly religious poems and includes texts by Richard Rolle, giving evidence of works by that author which are now lost; and the third section contains a medical treatise, the Liber de diversis medicinis. Brewer cites The Lincoln Thornton Manuscript’s historical value since it represents a rare contemporary witness to much of its content. The manuscript is also seen as evidence of a change in religiosity taking place during the fifteenth century, when a broader dispersion of religious material allowed the laity through vernacular texts an increasing ability to instruct themselves on religion and other topics.

Morris first came across the trilogy while a student at Oxford University and the works became one of his favorite reads, according to Sydney Cockerell, Morris’ secretary. At Oxford, he also became close friends with Edward Burne-Jones in 1852 and bonded over a shared love of poetry. Their lifelong collaboration resulted in some of the most beautiful books of the nineteenth century, influencing generations of printers and artists to the present day.

Burne-Jones illustrated the frontispiece in all three books. Morris so enjoyed his illustrations that he asked Burne-Jones to paint them on the walls of his home. Burne-Jones moved in radical circles, too. Both men were associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of British artists and writers who sought inspiration from the art created before the painter Raphael (1483–1520) and who glorified medieval and early Renaissance Italian art. The Pre-Raphaelites strove to return to what they saw as the pure ideals of an earlier time. Many of the friends that Morris, Burne-Jones, and the other Pre-Raphaelites met in college became their creative collaborators for life.

All three books were also edited and distributed by Frederick Startridge Ellis (1830–1901), an English bookseller and author. Ellis had a wide circle of literary and artistic friends. He was a publisher, on a small scale, and brought out the works of Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who became close friends. Among other associates were A. C. Swinburne, Burne-Jones and John Ruskin, whose Stray Letters to a London Bibliopole were addressed to Ellis and republished by him (1892). Ruskin referred to him as “Papa Ellis”. In 1864, Morris was introduced to Ellis by Swinburne, and after Morris’ death, Ellis served as one of the poet’s executors.

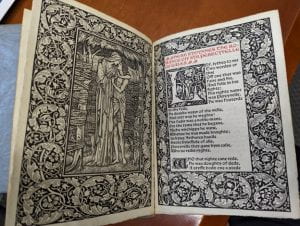

The Romance of Syr Perecyvelle of Gales (1895)

Syr Perecyvelle of Gales opens with the young Percival saying farewell to his mother before he goes off to find his fortune as a knight. The scene is the forest where she raised him in hopes of protecting him from outside influences. Burne-Jones’s image, informed by medieval aesthetics and fifteenth-century woodcuts, shows Percival enveloped by his mother’s embrace, within a thatch-roofed hut made from trees and branches. Set within a floral border designed by Morris and reminiscent of illuminated manuscripts, the scene is both poignant and foreboding. Percival’s mother is unable to protect him forever, and, at the end of this version of the story, he is slain in the Holy Land.

William Morris at the Kelmscott Press., Upper Mall, Hammersmith. Hammersmith, Kelmscott Press., 1895. 8mo. Upper Mall, Hammersmith. Printed by William Morris at the Kelmscott Press. 1895. Limited Edition. Octavo. 98pp. Original quarter linen and blue-gray paper covered boards; a few pencil notations on the front free endpaper, else a fine copy. One of three hundred fifty copies. Printed in black and red from Chaucer types, title-page woodcut border after Burne-Jones, with the first line of text in red, on Batchelor’s handmade paper.

Overseen by F.S. Ellis. 8 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches, One of 350 copies (of a whole edition of 358). Frontispiece by Edward Burne-Jones. Printed in Chaucer type, with titles and shoulder notes in red, and with numerous borders and initials designed by William Morris. Interior fine. Linen backed boards, very good: spine extremities a bit worn, two bottom corners worn, covers a bit faded, edges damp stained. Printed in red and black, wood engraved frontispiece, ornamental woodcut borders and initials. (Peterson A33). Quarter linen and blue-gray paper cover boards.

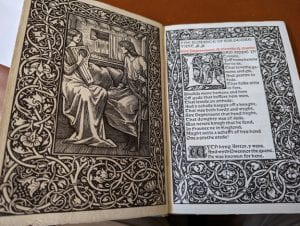

The Romance of Sir Degrevant (1896)

Sir Degrevant is generally classified as a composite romance, that is, a romance that does not fit easily into the standard classification of romances. It is praised for its realism and plot and is notable for its blending of literary material and social reality.

The title character, while a perfect knight in many respects, is initially reluctant to love. His life changes when he seeks redress from his neighbor for the killing of his men and damages done to his property. He falls in love with the neighbor’s daughter, and after she initially denies him her love, she accepts him. They both convince the overbearing and initially violent father to grant Degrevant his daughter’s hand in marriage.

William Morris at Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896 [but issued in 1897]). 215 x 150 mm. (8 1/2 x 6″). 2 p.l., 81, [1] pp. Edited by F. S. Ellis. ONE OF 350 COPIES on paper (and eight on vellum). Original holland-backed blue-gray paper boards, edges untrimmed, in a later (but old) glassine wrapper. Woodcut frontispiece designed by Edward Burne-Jones, elaborate woodcut borders of vines, flowers, and tendrils around frontispiece and first page of text, decorative woodcut initials (mostly three-line) throughout. Printed in red and black in Chaucer type. The wrapper with a few imperfections though extremely well preserved. According to Sparling (op cit), “This book, subjects from which were painted by Burne-Jones on the walls of the Red House, Upton, Bexley Heath many years ago, was always a favourite with Morris.” Because Burne-Jones’ frontispiece was not printed until 18 months after the text was ready, the book was published later (on 12 November 1897) than the date of the colophon (14 March 1896).

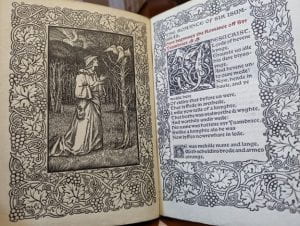

The Romance of Syr Isumbras (1897)

Sir Isumbras is a medieval metrical romance written in Middle English and found in no fewer than nine manuscripts dating to the fifteenth century. This popular romance must have been circulating in England before 1320, because William of Nassyngton, in his work Speculum Vitae, which dates from this time, mentions feats of arms found in Sir Isumbras. Unlike the other romance stories, the Middle English Sir Isumbras is not a translation of an Old French original.

Sir Isumbras is a proud knight who is offered the choice of happiness in his youth or his old age. He chooses the latter and falls from his high estate by the will of Providence. He is severely stricken; his possessions, his children and, lastly, his wife, are taken away; and he himself becomes a wanderer. After much privation he trains as a blacksmith, learning to forge his armor anew, and he rides into battle against a sultan. Later, he arrives at the court of the sultan’s queen, who proves to be his long-lost wife. He attempts to Christianize the Islamic lands over which he now rules, provoking a rebellion which is then defeated when his children miraculously return to turn the tide of battle.

Limited First Edition. First Printing. 8vo (21.1 x 14.3 x .8 cm). Bound in publisher’s original hardcover quarter Holland-backed blue paper boards, with white linen spine and black titles to cover. One of 350 [at twelve shillings] paper copies (plus 8 [at four guineas] on vellum). Printed on fine, hand-made, Batchelor (with the Flower watermark) paper. Uncut, deckled edges. Colophon and the smaller, rectangular printer’s device designed by Morris (no. 1). [vii], [title], [ii], 41, [viii] pp. Printed in black and red throughout in the Chaucer type designed by Morris. Head-title and shoulder-notes in red. Two full-page ornamental borders (4a and 4), with a woodcut frontispiece designed by Sir Edward Collier Burne-Jones. One 10-line and numerous 3-line woodblock initial capitals designed by Morris for his press, engraved by William Harcourt Hooper.

– David de Lorenzo, Giustina Director, SCUA

References

Anderson, Patricia. 1991. British literary publishing houses, 1820-1880. Detroit : Gale Research (UO Libraries, Z326 .B67 1991).

Brewer, Derek S.; Owen, A.E.B. 1977. The Thornton Manuscript (Lincoln Cathedral MS.91). London: The Scolar Press. (UO Libraries, PR1120 .L5 1975).

Connolly, Margaret (editor). 2008. Design and distribution of late medieval manuscripts in England. York, England : York Medieval Press, The University of York ; Woodbridge, UK ; Rochester, NY : In association with Boydell Press. (UO Libraries, Z106.5.G7 D47 2008).

Halliwell, James O. 1844. The Thornton Romances: The Early English Romances of Perceval, Isumbras, Eglamour, and Degravant. London, Printed for the Camden Society, by J.B. Nichols and Son (UO Libraries, DA20 .C17 no. 30).

Hudson, Harriet (Harriet E.). 1996. Four Middle English romances. Kalamazoo, Mich. : Published for TEAMS in association with the University of Rochester by Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. (UO Libraries, PR2064 .F68 1996.)

Morris, William and Sydney Cockerel. 1898. A note by William Morris on his aims in founding the Kelmscott Press: together with a short description of the press. (UO Libraries, Z232.M87 M83 1898).

Peterson, William S. 1991. The Kelmscott Press : a history of William Morris’s typographical adventure. Berkeley, Calif. : University of California Press. (UO Libraries, Z232.M87 P45 1991).

Sparling, H. Halliday (Henry Halliday). 1924 The Kelmscott press and William Morris master-craftsman. London : Macmillan and Co., Limited. (UO Libraries, Z232.M87 S73).

Taraba, Suzy. HISTORICAL ROW: SYR PERECYVELLE OF GALES: A BRILLIANT ASSOCIATION. Wesleyan University Magazine. 2016 ISSUE 1, Historical Row, Short Features, April 6, 2016.