Greetings from the Land of Enchantment and Colorful Colorado!

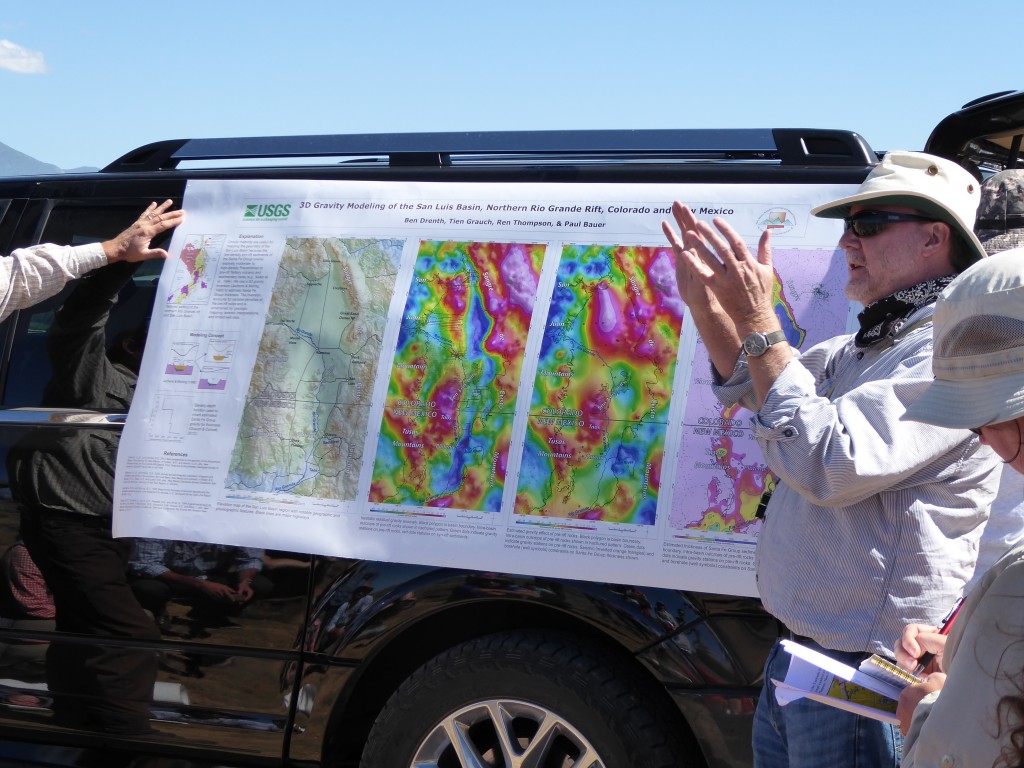

Welcome to the semi-official blog following the adventures of a group of graduate students and professors from the Department of Earth Sciences at University of Oregon (UO). We are also privileged to be in the company of USGS researchers from the “Cenozoic Landscape Evolution of the Southern Rocky Mountains” project, who are highlighting their latest findings which are transforming our understanding of this region of Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado. Our trip leaders are Dr. Mike Dungan (UO) and Dr. Ren Thompson (USGS), who have been working in this unique part of the world for decades, since Ren did his PhD research in the area under Mike Dungan.

This is a Staples’ Field Trip, which is supported by a fund in honor of Dr. Lloyd W. Staples, who spent his career as a Professor of Geological Sciences at UO, and has supported UO excursions to incredible geologic locations near and far. From the mouths of our esteemed trip leaders, the aim of this trip is to provide

a synthesis of accumulated knowledge and our collective contributions to an understanding of the Oligocene‐to‐present‐day evolution of the northern Rio Grande Rift and the voluminous Oligocene calc‐alkaline volcanism that preceded the onset of rifting. The underlying theme of this trip is how volcanism and tectonic setting changed in relation to each other over the last 35 Ma, and this will be explored on the basis of physical volcanology, rift‐basin structure and volcano‐sedimentary stratigraphy, a wealth of new geochronologic and geophysical constraints, landscape evolution, and igneous petrology. This trip will feature the integration of different types of information to develop a regional perspective, and insights gained from iconic examples of geologic phenomena.

Whew – quite a endeavor! Follow this blog to see how our geologic enlightenment turns out!

note: the oldest posts are at the bottom of the page

Visit the rest of our department at: http://earthsciences.uoregon.edu/

Check out the USGS project page on the Southern Rocky Mountain volcanism: http://gec.cr.usgs.gov/projects/srm/volcanism.shtml

![Basal mudstones, lacustrian deposits (or maybe surges?? [probably not]), draping plinian pumice deposit, and base of the massive Fish Canyon Tuff. This site has, and continues to, cause much controversy](https://blogs.uoregon.edu/staples2016/files/2016/09/P1010491-2kug5l0-1024x256.jpg)