World War II and the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council

“I just can’t find sufficient words to describe my gratitude for all that your office has done for me and other Niseis. In our darkest hour you brought forth your loving hands and gave us new hopes and inspiration. Surely Democracy can not and will not die as long as such groups like yours and Colleges that uphold the true ideals of Democracy exist…”

— anonymous words of a Japanese-American student upon receiving clearance to continue university study in 1942

The entry of the United States into World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, had serious impacts on approximately 110,000 Nisei (American citizens of Japanese descent) living in Oregon and throughout the west coast. After the creation of the War Relocation Administration on March 18, 1942, families from California, Washington, Oregon, and Arizona were uprooted to internment camps for the duration of the war. The evacuations and internment disrupted the normal rhythms of life for all 70,000 Japanese-American citizens and the 40,000 resident aliens on American soil. In addition to removing Japanese-Americans from the workforce and shuttering businesses, the evacuation orders also impacted students of Japanese descent at colleges and universities throughout the Pacific region, who were left with uncertainties about the potential for continuing their education.

The entry of the United States into World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, had serious impacts on approximately 110,000 Nisei (American citizens of Japanese descent) living in Oregon and throughout the west coast. After the creation of the War Relocation Administration on March 18, 1942, families from California, Washington, Oregon, and Arizona were uprooted to internment camps for the duration of the war. The evacuations and internment disrupted the normal rhythms of life for all 70,000 Japanese-American citizens and the 40,000 resident aliens on American soil. In addition to removing Japanese-Americans from the workforce and shuttering businesses, the evacuation orders also impacted students of Japanese descent at colleges and universities throughout the Pacific region, who were left with uncertainties about the potential for continuing their education.

The work of men like Karl W. Onthank, who spearheaded the relocation effort at the University of Oregon, helped hundreds of American students of Japanese descent transfer to universities and colleges outside of the evacuation zones to continue their studies. “Most of them are keen, alert young men and women headed toward professional or important business activities. They are, so far as I have talked with them—and I have talked with a good many—surprisingly unresentful of the popular demand to move them back from the coast,” Onthank noted about the Japanese-American students on the UO campus. “If they are thrown out of college and can do nothing but mark time the next few years it would not only be too bad, but would involve a very grave risk of developing antagonisms which do not yet exist.”

Beginning in early 1942, when rumors about the evacuation and internment of Japanese-Americans on the west coast started to circulate, Onthank and other western university administrators worked to find new programs of study for this group of affected students. 22 students of Japanese descent started the 1941-1942 academic year at the University of Oregon; by the end of the school year, when evacuation orders were issued for the west coast, only a dozen still remained on campus. While World War II affected many of the students on campus, it proved to have an outsized impact on Nisei students as well as Japanese-American graduates of the University of Oregon.

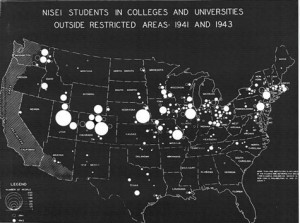

The National Japanese American Student Relocation Council assisted thousands of students on the west coast in finding new universities where they could continue their course of study. At least 10 from the University of Oregon were provided new educational opportunities. Three sophomore students — Samuel Naito, Kenzo Nakagawa, and George Uchiyama — transferred to the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. After graduation, Naito served as CEO of his family’s real-estate corporation in Portland and also served as president of Made in Oregon. Uchiyama continued his education after receiving his undergraduate degree in Utah, later graduating with honors from the St. Louis School of Dentistry before becoming a world-renowned orthodontist.

Chiye Arai moved to the University of Minnesota, while Mary Furusha relocated to Barea, Ohio to study at Baldwin-Wallace College. Another student, Alice Kawasaki, was pulled from campus prior to the end of the term along with other nursing students to work in Portland. She would later move to New York to finish her nursing degree. Others, such as Tadashi Osaki, chose to continue extension work at Oregon via correspondence classes.

But not everyone was able to continue on with their education. Takuo Kawaushi was ordered to report to Army basic training, while Frank Hachiya served in the Pacific theater and was killed in action in December 1944 during engagements in the Philippines. Hachiya would posthumously receive a Silver Star for his service during the war.

The largest exodus of UO students was to the state of Colorado. Makoto Iwashita relocated to the University of Colorado in Boulder before later continuing his studies at New York University, while three others — Grace Ikuko Kumazawa and the siblings Michi and Shu Yasui — moved to the University of Denver. Kumazawa would eventually complete her degree in microbiology at the University of Missouri. Shu Yasui, who initially evaded the evacuation orders, moved on to Philadelphia after a brief period in Denver, changing his first name to Robert and graduating from Temple University Medical School before serving in the Army Medical Corps.

Michi Yasui, who was a senior at Oregon at the time of the relocation orders, was a major topic of debate about the enforced curfew before the evacuation orders had officially been issued. Onthank and other university administrators were in communication with the military and civilian authorities about the possibility of allowing Yasui to attend the commencement ceremony on May 31, 1942 taking place three blocks from her dorm at McArthur Court, however the ceremony began at 8:00PM after the enforced curfew. Although Onthank and others lobbied extensively on her behalf, the Wartime Civil Control Administration denied their request; Yasui was forced to remain in her dormitory and missed her graduation. Although she was unable to attend her graduation, after a clandestine departure from Eugene she successfully joined her brother Shu in Denver. She would have to wait 44 years before finally receiving her UO degree in 1986.

The war relocation projects also affected former UO students. Thomas Hayashi, a 1939 graduate of the psychology department from Astoria, had returned to the university to continue graduate studies in 1941. During the same academic year, his graduate work was interrupted by the forced relocation of Nisei citizens. Hayashi was eventually forced to relocate to Chicago, where he opened a business and remained until his death.

Perhaps the most famous case regarding a former Oregon student is that of Minoru Yasui, the older brother of Michi and Shu. Minoru earned his undergraduate degree from the University of Oregon before becoming the first Japanese-American graduate of the UO Law School in 1939. Yasui was a practicing attorney in Portland when the government implemented Executive Order 9066, which placed a curfew on all citizens of Japanese descent. Yasui, hoping to challenge the Constitutionality of the executive order, spent three hours walking around downtown Portland in defiance of the curfew on the night of March 28, 1942. After three hours walking around downtown Portland, Yasui was arrested and convicted for breaking the curfew — a conviction that would be upheld by the United States Supreme Court in a landmark June 1943 ruling.

The experience guided Yasui’s work for the remainder of his life. After the war Yasui settled in Denver, where he was forced to challenge his criminal record to practice law. His human-rights efforts resulted in several awards from the American Civil Liberties Union, including the E.B. MacNaughton Award from the ACLU of Oregon which he received in November 1983. Yasui was also recognized by the U.S. Department of Justice, the Oregon State Bar Association, and the Japanese American Citizens League. He passed away in November 1986, two years before the efforts of his lifetime yielded the enactment of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which led to a formal apology to victims of the internment policy and restitution of $20,000 for every living survivor of the internment camps.

The legacy of Japanese-American students at the University of Oregon has been recognized several times in recent decades. In 2007, the Oregon legislature passed House Bill 2823, which authorized Oregon’s universities to award honorary degrees to students whose educational opportunities were abridged by World War II. 19 students received honorary degrees from the University of Oregon on April 6, 2008 as a result of the bill’s passage. We honor these courageous individuals who persevered though such adversary and hope that their legacy will continue to be remembered, honored and celebrated.

Information for this article was collected from the following sources:

- Office of the Dean of Personnel Administration. National Japanese American Relocation Council Records, UA 009, Special Collections & University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, Oregon.

- Lauren Kessler, Stubborn Twig: Three Generations in the Life of a Japanese American Family (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2008).

- Peter Monaghan, “U. of Oregon Awards Honorary Degrees to Japanese Americans Who Were Expelled in 1942,” Chronicle of Higher Education, April 10, 2008.

- Photos sourced from the UO Archives Digital Photo Collection and the University of Oregon Yearbooks Archives.

Zach Bigalke

Student Research Assistant

I am Robert Shu Yasui’s daughter. Shu Yasui was a freshman when the war broke out. His father, Masuo, a successful businessman and community leader from Hood River, had been picked up by the FBI as a “potentially dangerous enemy alien” several days after the Pearl Harbor attack. Masuo spent the war in special camps run by the U.S. Justice Department. The family assets were frozen by the government and the family remaining at home, including Shu’s mother, brother, and sister, were eventually interned in camps in California and Montana. Shu’s parents had worked hard to send their children to college, and counseled them that education was the way to counter prejudice and discrimination. Shu knew that the evacuation orders would force him to leave school – which was not what his parents would want – so he left campus at night, seeking safer haven in Denver, beyond the evacuation boundaries. He made it safely and sent word to sister Michi to try it as well. With the help of a minister and Japanese American students, they continued their education while working their way through school. Shu later transferred to the University of Wisconsin, and got a job as an orderly at the University hospital, only to lose it when administrators feared his employ would jeopardize security at their research facilities. He applied to medical schools across the country, and was rejected by all of them, probably due to ethnicity. Temple University in Philadelphia – home to a student relocation program run by local Quakers – accepted him based on his grades. He enrolled during the equivalent of his senior year – never having received his undergraduate degree. After completing medical school at 21, he did his surgical residencies in Pennsylvania, and then was drafted into the U.S. Army, where he served as a major in the medical corps in post-war Germany.

Thank you very much for this additional information. We are always looking to fill in these stories further, and your comments are greatly appreciated.