Untold Stories: Black History at the University of Oregon

In honor of Black History Month, Special Collections and University Archives is highlighting some historic figures and events in the century-long history of African Americans at the University of Oregon. These often untold stories represent the determination and strength of the black community at the university as they fought state and institutional challenges. From the era of Oregon’s exclusion laws to the present, African American students and faculty have persevered under often difficult circumstances. What follows below are the stories of several notable people in the UO campus community as well as those events that have shaped the course of African American history at the University of Oregon.

In honor of Black History Month, Special Collections and University Archives is highlighting some historic figures and events in the century-long history of African Americans at the University of Oregon. These often untold stories represent the determination and strength of the black community at the university as they fought state and institutional challenges. From the era of Oregon’s exclusion laws to the present, African American students and faculty have persevered under often difficult circumstances. What follows below are the stories of several notable people in the UO campus community as well as those events that have shaped the course of African American history at the University of Oregon.

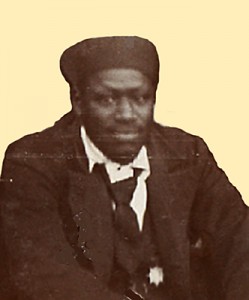

Wiley Griffon

Wiley Griffon (1867–1913) was the first African American employee at the University of Oregon. In the late 1890s he worked as a janitor at the Men’s Dormitory, Friendly Hall. Although he was not the first or the only African American in Eugene, he was the first one mentioned by name as being a resident. Despite the exclusion laws in effect at the time, which forbade the presence of nonwhite American citizens in Oregon, Griffon and other minorities came to live in Eugene.

Wiley Griffon (1867–1913) was the first African American employee at the University of Oregon. In the late 1890s he worked as a janitor at the Men’s Dormitory, Friendly Hall. Although he was not the first or the only African American in Eugene, he was the first one mentioned by name as being a resident. Despite the exclusion laws in effect at the time, which forbade the presence of nonwhite American citizens in Oregon, Griffon and other minorities came to live in Eugene.

Griffon first arrived in the city in 1890. Prior to working at the university he served as the driver of the town’s first streetcar service — a single mule-powered car that ran on narrow-gauge tracks from the Southern Pacific Railway station to the university. According to the Eugene Morning Register, Griffon served numerous roles, including “driver, conductor, dispatcher, and largely the motive power by persistently shoving along the ambling mule.” He took the job at the university when the streetcar eventually shut down. In addition to working at UO, he took on various other jobs, including working for “Grandma Munro at her famous eating house on the O.R. & N. line at Meacham,” serving as “a waiter on a dining car on the railroad,” and working “at many odd jobs in Eugene and at other points in the valley,” said the Eugene Daily Guard. He eventually owned a home overlooking the Millrace on the site of what is now EWEB’s employee parking lot. When he died in 1913 he was working at the Elks Club in Eugene.

Despite living in a time and place that was not welcoming to African Americans, evidence suggests he weathered those times positively and was mostly respected in return. Griffon is buried in the Eugene Masonic Cemetery, but his tombstone went missing at some point. However, when Eugene residents and students realized this unfortunate situation, funds were raised and donated to erect a historic monument and plaques at the Lane Transit District and Eugene Water and Electric Board offices. Major financial supporters and coordinators of this project included the Lane Community College Black Student Union and the “I Too, Am Eugene: A Multicultural History Project.”

Mabel Byrd

While at the University of Oregon, Byrd was the only black resident of Eugene. Because school and state policy prohibited her from living in the campus dormitories because of her race, Byrd lived in the home of history professor Joseph Schafer. There she worked as a domestic for the Schafer family while attending the university.

Born in Cannonsburg, Pennsylvania on July 3, 1895, Byrd moved with her family to Portland as a youth at a time when exclusion laws effectively forbade the presence of nonwhite American citizens in Oregon. Her father, Robert, worked as a bricklayer in the city. In Portland, Byrd was the only African American student in her class at Washington High School, preparing her to face similar circumstances upon arriving in Eugene.

After transferring to the University of Washington, where she obtained a B.A. in Liberal Arts, Byrd was a key activist in the early Civil Rights movement. Collaborating with national leaders like W.E.B. DuBois, Byrd became active with the YWCA, NAACP, the League of Nations, and other national and international organizations promoting greater equality for non-whites. She later worked as a research assistant at Fisk University investigating conditions in segregated schools; supervised the implementation of codes designed to insure equal pay, working conditions, and employment opportunities for African American citizens under the auspices of the National Recovery Administration under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal; and served as the executive director of the People’s Art Center in St. Louis. Byrd passed away at age 92 on May 20, 1988 in St. Louis, Missouri.

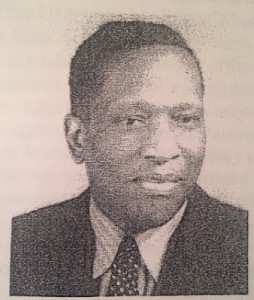

Dr. William Sherman Savage

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Howard University in Washington, DC in 1917, William Sherman Savage came to Eugene in 1924 to continue graduate work in history. Two years later, he was the first African American to graduate with a Master of Arts from the University of Oregon. During his time in Oregon, Savage was forced to deal with the isolation of being the only black person in Eugene, which at the time was a center for Ku Klux Klan activity in the state.

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Howard University in Washington, DC in 1917, William Sherman Savage came to Eugene in 1924 to continue graduate work in history. Two years later, he was the first African American to graduate with a Master of Arts from the University of Oregon. During his time in Oregon, Savage was forced to deal with the isolation of being the only black person in Eugene, which at the time was a center for Ku Klux Klan activity in the state.

Savage chose the University of Oregon to complete his MA after spending time at the University of Kansas during the summers of 1921 and 1923. He decided to attend UO because “the tuition was only six dollars a quarter. All I had to do was find a place to stay.” Unable to live on campus because of school and state policies denying residence in university dormitories due to race, Sherman struggled to find off-campus housing in the city. With Klan members holding strong positions in Eugene and the state, Savage was forced to confront overt discrimination during his time at UO.

Upon completion of his master’s thesis, “Abolitionist Literature in the Mails, 1835-36,” Savage graduated from UO with a Master of Arts with a major in history and a minor in education. He later completed a Ph.D. in history at Ohio State University in 1934, and served as a professor in the history department at Lincoln University in Missouri for nearly four decades until his retirement in 1960. He settled in Hawkins, Texas, where he served as the chairman of the Department of History and Social Sciences at Jarvis Christian College. In 1970, Dr. Savage returned to the classroom as a visiting professor of history at California State College in Los Angeles before concluding his career at the prestigious Huntington Library in San Marino, California

Throughout his career, Dr. Savage was one of the most respected African American historians in the country, focusing on the role of African-Americans in the development of the western United States. In the words of his colleague at Huntington Library, Ray Allen Billington, Dr. Savage “labored alone and selflessly to bring recognition to the blacks who had played such a significant role in the western process.” His seminal work, Blacks in the West, remains one of the key texts detailing black contributions to westward expansion.

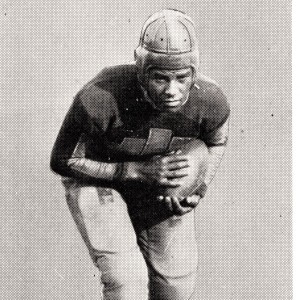

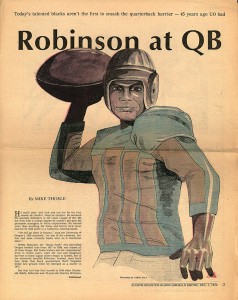

Bobby Robinson and Charles Williams

In the fall of 1926, the same year that Oregon finally repealed its exclusion law that forbade blacks from entering or owning property in Oregon, 19-year-old Bobby Robinson and 22-year-old Charles Williams, two young high school football stars from Portland (at Jefferson High School and Washington High School, respectively), became the first black student-athletes at the University of Oregon.

When Robinson and Williams first arrived at the university in 1926 they encountered a campus not yet ready to embrace them in all aspects of everyday life. According to an article in the Register-Guard Emerald Empire (Dec. 1, 1974), Williams noted that since the university recruited them as full-fledged scholarship athletes and students, neither man anticipated any difficulties. And they were correct, except in one area—university housing.

Apparently concerned over how the black men living in university dorms would be accepted by the larger campus and Eugene citizens, the university instead required that Robinson and Williams live off-campus for their first year. In recalling this situation, Williams reflected, “They were afraid – that’s what I thought. It was a Ku Klux town and they thought there might be trouble from the townspeople. We accepted that.” Thus, they lived in an apartment at 825 E. 13th Street (currently occupied by Espresso Roma), which actually became a popular retreat for the other athletes and students who were weary from fraternity hazing.

The university’s perspective toward allowing the two to live on campus would only change after their white teammates signed a petition demanding they be allowed to live on campus. By their sophomore year in 1927, the university permitted Williams and Robinson to live in the men’s dormitory, Friendly Hall. Rather than being given a room in the main part of the building, however, they were forced to occupy an apartment that was part of the dormitory but which had an outside entrance. As Williams reflected on this situation, “I suppose to the university it wasn’t quite the same as putting us right in the dorm, but it was to everyone else. We had the use of the dorm. We were right with the fellows we knew. We visited back and forth and did everything we wanted.”

Although the living situation initially challenged them, Williams and Robinson went on to have illustrious football careers at the university from 1926 to 1930. Both were moved up to varsity after their freshman year and took turns starting the games—fast becoming favorites of Webfoot fans of the day. The university wasn’t always as willing to stand up for their stars as their teammates, though; Oregon capitulated to Florida’s demands that the two players not participate in the 1929 game in Miami. Eventually Robinson earned his bachelor’s degree in physical education. However, although Williams completed four years of college, he did not earn a degree due to a change in major.

Civil Rights Era

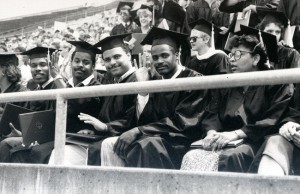

Due to years of restrictive legislation, including the exclusion law, it was not until after World War II that the black population increased in the state and on the UO campus. At the beginning of the Civil Rights era, students and faculty began to address the issues of race and discrimination. In the early 1950s, these issues coalesced when students began to discuss the status of “white and colored races,” as well as reinstituting an inactive chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on campus.

In 1951, a small group of black and white students initially contended that the NAACP was not needed on campus as they felt that the most significant discrimination came directly from individuals and not from the administration. Furthermore, they realized that “no NAACP can erase a mental set or 20 some years of background which says ‘you’re superior to the black and yellow people’.” However, they realized many projects and initiatives could be begun within the NAACP. Consequently, in 1952 the students reinstituted the official chapter of the NAACP on campus which went on to host numerous speakers, discussions, and events addressing discrimination, race relations, and cultural contributions.

Edwin Coleman II

Edwin Coleman II began his career at the University of Oregon in 1966, moving to Eugene from Chico, California to take a position an instructor and technical director for theater studies. Born in 1932 in El Dorado, Arkansas, Coleman had previously worked in the drama departments at San Francisco State University and Chico State University. While working at UO, he earned his Ph.D. from the university in 1971. That year, Coleman was hired as an English professor after the administration sought to introduce more African American literature. His work within the department would serve as the impetus for the development of Ethnic Studies on campus and an increased focus on African American literature.

Edwin Coleman II began his career at the University of Oregon in 1966, moving to Eugene from Chico, California to take a position an instructor and technical director for theater studies. Born in 1932 in El Dorado, Arkansas, Coleman had previously worked in the drama departments at San Francisco State University and Chico State University. While working at UO, he earned his Ph.D. from the university in 1971. That year, Coleman was hired as an English professor after the administration sought to introduce more African American literature. His work within the department would serve as the impetus for the development of Ethnic Studies on campus and an increased focus on African American literature.

Coleman immediately set out to redesign several courses within the permanent English curriculum. Emphasizing the importance of African American and other minority literature, Coleman recognized the value of these underutilized resources to undo racist mindsets and economic disparities within the culture. In an oral interview in 1994, Coleman said of his early career at UO:

“I was delighted that my colleagues and department chair trusted my judgment and my scholarship well enough to allow me to evaluate and expand the courses in the direction that I envisioned. There are very few places where you can go and have that kind of liberty.”

Coleman also sought to reference literature within the context of the times in which it was written. Drawing upon his own experiences during the Civil Rights movement, Coleman incorporated history, politics, sociology, and philosophy into his lessons to help students better understand the motives that underpinned the writings he introduced.

In addition to his academic career, Coleman also performed for decades as a professional bass player. His talent led him to perform with artists such as Peter, Paul and Mary, Cal Tjader, the Kingston Trio, and Mel Torme. “In my heart of hearts I’m a musician,” Coleman said about his musical career. “I didn’t like the rigors of the road. I was also not willing to be away from my family.” Though he no longer toured, Coleman continued to perform in a jazz trio in his time away from campus.

In 1981 Coleman became the associate director of the Folklore and Ethnic Studies Program at the University of Oregon. Four years later, he took over as director of Ethnic Studies, in which capacity he served until his retirement from the university in 1998. The increased emphasis on African-American literature and Ethnic Studies is a testament to his dedication throughout more than three decades serving the UO community.

Creation of the Black Student Union

In 1966, students created the Black Student Union (BSU) to bring awareness to racial discrimination and to serve as a coalescing group for activism regarding these issues. Indeed, in April 1968, the BSU submitted a list of grievances and demands to then President Arthur Flemming. One outcome of these requests included a report proposing funding of a “Task Force on Black Studies.” This report also provided detailed background about the previously created “Committee on Racism,” as the Black Studies initiative grew out of one of the Sub-Committees on Academic Affairs. Accordingly to the report,

In 1966, students created the Black Student Union (BSU) to bring awareness to racial discrimination and to serve as a coalescing group for activism regarding these issues. Indeed, in April 1968, the BSU submitted a list of grievances and demands to then President Arthur Flemming. One outcome of these requests included a report proposing funding of a “Task Force on Black Studies.” This report also provided detailed background about the previously created “Committee on Racism,” as the Black Studies initiative grew out of one of the Sub-Committees on Academic Affairs. Accordingly to the report,

“[T]he proposal for the establishment of a School of Black Studies is a major part, but one part only, of a concentrated and whole-hearted effort at institutional reform in the light of what all sane men agree to be the most pressing current social and academic needs.” (pg. 7)

You can read additional documents regarding this initiative, and the larger civil rights issues occurring on campus, in the digital collection of the Papers of the Presidents: http://oregondigital.org/digcol/uopres/

From the 1970s to the Present

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Black Student Union expanded its efforts in numerous areas, especially concerning awareness surrounding culture, arts, and education. The BSU continued to build strong bonds with other groups across campus, including Student Affairs, the Office of Multicultural Academic Success, and the Council for Minority Education, and remained the go-to place for black students on the UO campus. In addition, due to the initiatives spearheaded and developed by BSU in the 1960s, the enrollment and graduation rates for black students increased.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Black Student Union expanded its efforts in numerous areas, especially concerning awareness surrounding culture, arts, and education. The BSU continued to build strong bonds with other groups across campus, including Student Affairs, the Office of Multicultural Academic Success, and the Council for Minority Education, and remained the go-to place for black students on the UO campus. In addition, due to the initiatives spearheaded and developed by BSU in the 1960s, the enrollment and graduation rates for black students increased.

Today black students remain a driving force behind strong activism regarding issues of race and ethnicity. Students most noticeably took an active stance in addressing diversity concerns in the mid to late 2000s; the Black Student Union was ever present in this endeavor. Sparked by instances of cultural inefficiencies within the College of Education, black students used this as an opportunity to note larger campus climate issues as they pertained to students of color. In a series of meetings with central administration and various actions including the “Zero Awards” given to departments with no faculty or staff of color, black students along with additional students of color moved the campus forward in issues of equity, diversity and inclusion.

This information provided above is only a brief highlight of the major accomplishments and history of African Americans at the University of Oregon. Portions of the information highlighted above stems from a physical exhibit presented last year as part of Black History Month. As part of the Documenting UO History and Diversity Project, we are continuing to research and add to this history by working closely with alumni, students, and community allies. We are also looking for collections or records from alumni or community members that document this important history on campus. If you or someone you know has any documents or information to share as part of this project, please contact us.

Information for this article was collected from the following sources:

- Herman L. Brame, African American Athletes in Oregon: A History From 1804 to 1950 (Portland, Oregon: 2000).

- “Campus Discrimination Topic of NAACP Panel,” Daily Emerald, February 22, 1954, pg. 1.

- “Civil Rights,” Papers of the Office of the President, UO Libraries Digital Collections.

- Edwin Coleman II, interview with Heatherle Himes, March 8, 1994.

- “Does Oregon Need NAACP?,” Daily Emerald, January 10, 1951, pg. 2.

- Herman L. Brame, Dr. William S. Savage: The University of Oregon’s First African American Graduate (Portland, Oregon: 2014).

- Herman L. Brame, A Forgotten Woman of Oregon: Mabel Byrd’s Life of Protest (Portland, Oregon: 2014).

- “Minority Group Topic of NAACP,” Daily Emerald, February 27, 1956, pg. 7.

- Photos sourced from the University Archives Photographs, UO Archives Digital Photo Collection, the Alumni Publications/Old Oregon Archives, and the University of Oregon Yearbooks Archives.

Books, theses, and additional resources related to the subject of African-American history in Oregon include:

- Daniel G. Hill, The Negro in Oregon: A Survey (thesis, University of Oregon, 1932.)

- Kimberley A. Mangun, A Force for Change: Beatrice Morrow Cannady and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Oregon, 1912-1936 (Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2010.)

- Elizabeth McLagan, A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788-1940 (Portland: The Georgian Press, 1980.)

- Perseverance: A History of African Americans in Oregon’s Marion and Polk Counties (Salem, OR: Oregon Northwest Black Pioneers, 2011.)

- John Daniel Rothwell, Rhetoric by Slogan: The “Black Power” Phenomenon (thesis, University of Oregon, 1969.)

- Quintard Taylor Jr., “History of Blacks in the Pacific Northwest, 1788-1970” (doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan, 1977.)

- Quintard Taylor Jr., In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West. 1528-1990 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998.)

- Gwen Trice, Eric Cain, Eve Epstein, Emily Shreefter, Greg Bond, and Nick Fisher, The Logger’s Daughter (Portland: Oregon Public Broadcasting, 2009), DVD.

- Jon Tuttle, John Lindsay, Steve Gosson, Michael Bard, and Glenn Holstrom, Local Color (Portland: Oregon Public Broadcasting, 2008), DVD.

Jennifer O’Neal, University Historian and Archivist

Zach Bigalke, Student Research Assistant

Wow, thanks for posting! I remember this exhibit at the museum when it was there and I greatly appreciate that this history is readily available to read online as well. As UO students we should all know and respect the history of Black students here.