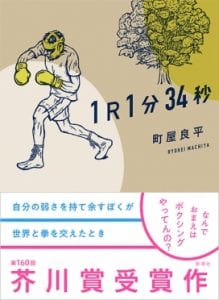

Machiya Ryōhei 町屋良平. 1 raundo 1 pun 34 byō 1R [ラウンド] 1分34秒. Shinchōsha, 2019.

This was the co-winner of the 160th A-Prize, for late 2018. The other co-winner was Ueda Takahiro 上田岳弘’s Nimrod ニムロッド.

It’s a boxing novel.

Ueda was born in 1983 and has been writing for about two years; this is his second time as a finalist for the A-Prize.

The story is narrated by a 22-year-old pro boxer who, as we learn on the first page, won his first bout by a knockout, but has gone for two losses and a tie since. He’s worried that he’s gone as far as he can go. The story follows him as he recovers from his last fight and trains for the next.

Early on in the story there’s a description of the room he lives in: spartan and small, but what’s described most vividly is the big tree outside his one window that keeps the place dim all day long. He likes this, and over the course of the novel this becomes emblematic, both of his life and the book: it’s all inward, sealed with no vista, and dim. At times this inwardness feels like the intense focus we expect from an athlete’s story, and at times it feels cramped and hopeless. The narrator himself spends a fair amount of time ruminating on the meaning of his life and what he’s doing with it, or at least wondering about it; it’s a sports story cut with existential anxiety.

This means that it walks a fine line between the jingoistic hang-tough sports stories that fill popular media (spokon manga) and the literary celebration of stoic manhood of, say, Hemingway. It has elements of each, but manages to avoid committing to either. Partly that’s accomplished by carefully limiting the timeline of the story to the space between bouts. We start in defeat, but not at the moment of defeat; rather we see the narrator reliving through video, memory, and dream his last bout. And we end on the eve of the next fight, with a last line that suggests he’s envisioning winning (by a TKO at 1:34 in the 1st round, thus the title), but we’re not there yet. So we don’t get the thrill of victory or the agony of defeat in the moment, but only in prospect and retrospect.

Instead what we get is process. It’s a highly technical account of a boxer’s training. We follow him in exhaustive detail through his routine: his daily workouts, his diet, his review of video of past matches, his research on his next opponent. Machiya is interested in showing us the physical, mental, and emotional punishment his boxer subjects himself to – not even in pursuit of his dream, because he’s starting to be unable to hope for much beyond the next match, and not even in pursuit of survival, because he contemplates death any number of times. In pursuit of himself? Probably: his next opponent is named, significantly, Shin, written heart 心, suggesting that the boxer is up against his deepest self.

There are three other characters in the book. One is the boxer’s friend, always identified as that: a guy who wants to become a filmmaker. He follows the boxer around filming him on his iPhone; also drags the boxer to art exhibits. Their bond is a curious one, as the boxer doesn’t particularly understand art, but doesn’t mind going to see it either. Doesn’t particularly like being filmed either, but ends up opening up more to the camera than to any real person. The second is a girl (always identified as that) who the boxer picks up at the gym, sleeps with a few times, and then breaks up with. She seems to largely be there to demonstrate the boxer’s commitment to his sport over any relationship, although she’s if anything more casual and unsentimental about the relationship than he is. The third is a slightly older boxer named Umekichi who steps in as his trainer and starts to challenge his approach and his regimen. There’s some old-fashioned martial-arts master-disciple stuff in here, but it’s not overdone; we’re never sure if Umekichi is really accomplished enough to make him worth the boxer totally trusting, or if he’s just the only one who can be bothered to try and help a guy on his way out.

All three of these characters seem meant to be seen as parts of the boxer’s process. He has a friend, i.e. just enough of a social life to keep him going. He has a girlfriend, i.e. just enough sex to keep him going. And he has a trainer, the only one he really pays much attention to, for obvious reasons. Further emphasizing the focus on process is the fact that we never meet any of his opponents: they exist only as memory or as imagination. We’re really focused, in this story, on what happens between fights, between the boxer and himself.

In that sense, it’s quite well realized.