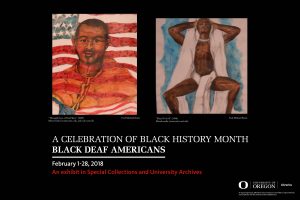

New Exhibit | Black Deaf Americans: History, Culture, and Education

— David de Lorenzo, Giustina Director

Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA) has recently mounted an exhibit focusing on Black Deaf Americans to celebrate Black History Month.

Black Deaf people have one of the most unique cultures in the world. The Black Deaf Community is largely shaped by two cultures and communities: Deaf and African-American. Some Black Deaf individuals view themselves as members of both communities. Since both communities are viewed by the larger, predominately hearing and White society as comprising a minority community, Black Deaf persons often experience an even greater loss of recognition, racial discrimination and communication barriers coming from both communities.

Little has been written about the Black Deaf community. Even though segregated schools existed until the mid-1950s, no historical analysis of that experience, its people, or events has been written. Only a handful of memoirs by Black Deaf individuals have been published. Recent interest in Black Deaf sign language has produced a seminal work on the subject, The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL, but much more research needs to be pursued. This exhibit seeks to highlight the history, experiences, and accomplishments of Black Deaf Americans through six themes: segregated schools for Black Deaf students, memoirs by Black Deaf adults, incarceration of Black Deaf, Black Deaf sign language, Notable Black Deaf, and artwork of Black Deaf. Some of the archival material exhibited is extremely rare and difficult to find. Several publications on exhibit are considered rare books. Even some recent titles on exhibit are difficult to find.

Segregation

Between the 1870s and 1970s, Deaf schools and departments were segregated for Black and White students, and they remained so until after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. These facilities, such as the Virginia School for Colored Deaf and Blind Children built in 1909, were documented by a rare postcard featured in the exhibition, pictured below. The nature of ephemera is unfortunately germane to the history of Black Deaf segregation, since the school buildings were demolished in 2017.

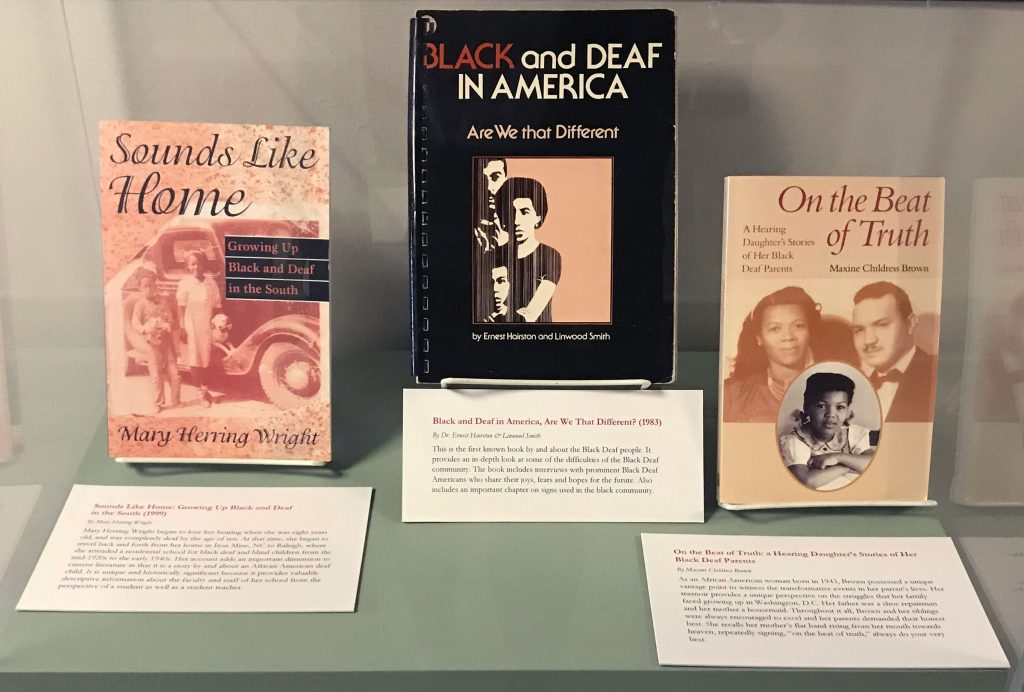

Memoirs

Black Deaf authors have written first-hand accounts of their experiences as individuals and members of the Black Deaf community, the first being Dr. Ernest Hairston and Linwood Smith’s Black and Deaf in America (1983).

Incarceration

Justice and legal professionals often lack Deaf cultural competency, which leads to disproportionate convictions, abuse, and isolation of Deaf Americans in the criminal justice system. This problem is magnified for Black Deaf Americans. This exhibit highlights accounts of institutional traumas experienced by Black Deaf Americans, such as John Doe No. 24 who, Black, Deaf, and Mute, was arrested as a teenager in 1945 and institutionalized in the Illinois mental health care system until his death in 1993.

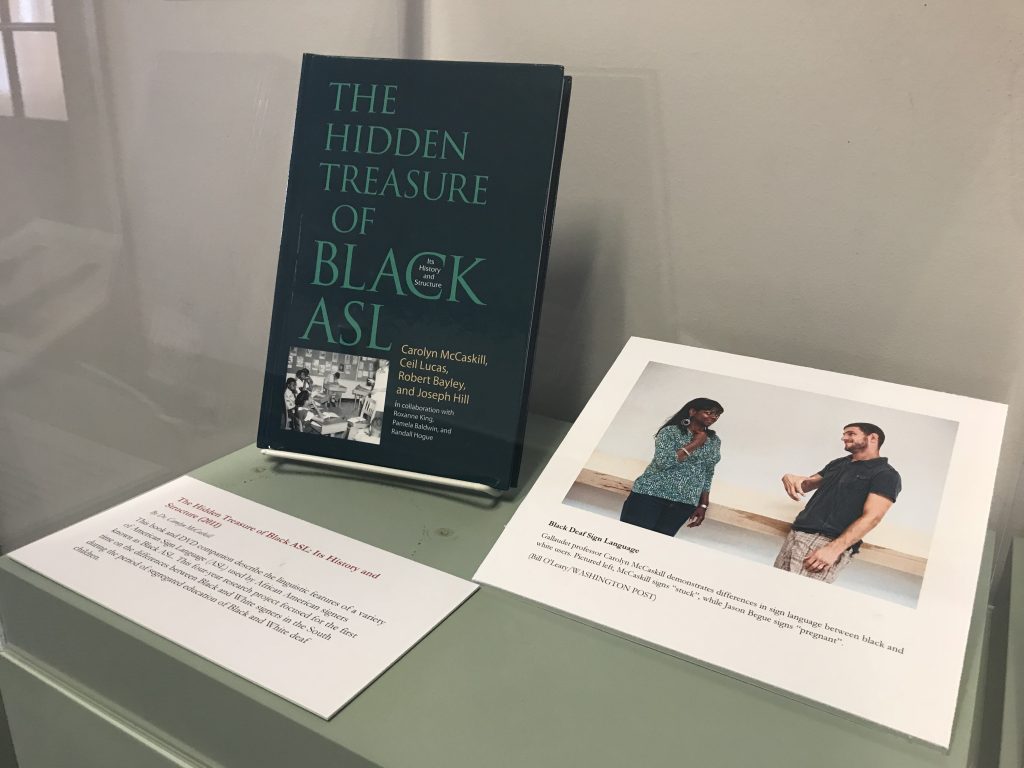

Black ASL

The Black ASL Project carried out by Gallaudet University’s Department of Linguistics and Department of ASL and Deaf Studies includes a team of researchers seeking to describe the linguistic varieties within ASL used by Black Americans. These differences are rich and may include general semantic differences carried over from spoken Black English, such as the sign for “bad” meaning “really good,” but Black ASL also features a larger signing space and use of facial grammar (Sellers, 2012).

We invite you to view this exhibit during February 2018 highlighting one of America’s most unique but underrepresented cultures.

References:

Sellers, F. S. (2012, September 17). Sign language that African Americans use is different from that of whites. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com

— David de Lorenzo, Giustina Director

This is AWESOME! Thank you so much for holding this exhibit! I came across this article and was excited to see that Black Deaf Americans are being recognized. Another book to add is the one Portland Community College in the Black Deaf Cultures Class shared, called “Unspeakable The Story of Junius Wilson”. Thank you!

Black Deaf students DID receive an education at the ASD, NYSD and Mt. Airy (PSD) BEFORE the Civil War.

NYSD (Fanwood) opened in 1818 with Horace Crawford, a Black Deaf student among its very first class. Sally Robinson would join him a year later.

ASD would enroll Charles Hiller in 1825. PSD would entoll its first Black Deaf student in 1839.

By the time the NC School for Colored Deaf and Blind opened in 1869, there were about 25 to 30 Black Deaf who had attended these 3 school.

When looking up information on the Education of Black Deaf on the internet, it is annoying to find repetition of the same information that appears to assume ,Black Deaf History began in the 1950s.

Andrew Foster is not the first Black Deaf person to graduate from Gallaudet. That honor goes to Hume LePrince Battiste from South Catolina who attended PSD.

In fact, the first Black Deaf person (known at this time) to earn a college degree was Thomas Flowers from PSD who earned his BA from Howard University in 1896.

It is true that Black Deaf History was minimized or erased and we see folks talking about Black Deaf people as if our history began in the 1950s.

My 19th Century Black Deaf History (DST403) and 20th Cenury Black Deaf History (DST595) classes at Gallaudet University basically debunks a lot of these myths. The Center for Black Deaf Studies at Gallaudet where I am co- director and research Scholar, continues to work towards setting the record straight.

A search for the first cohort of former Deaf slaves to enroll at the Governor Morehead Schol for Colored Deaf and Blind results in ZERO information. We believe that William A. Caldwell, Amanda Byers and Julius Carrett were among the first to enter in 1869. All 3 went on to become educators although the last 2 apparently had very brief teaching careers at the TBDO (Texas) when it opened.