Throughout history, forgeries have provided a window into the culture of the time. In the Middle Ages, Christians counterfeited relics of saints to substantiate supernatural beliefs. In twelfth century Europe, the forgery of legal documents, such as land grants, became a known practice to advantage the forger’s financial status. In the sixteenth century, it was common to invent one’s genealogy to elevate social status.

Forgeries and their forgers continue to attract interest in modern times and many libraries and museums have mounted comprehensive exhibitions on the subject. In 1990, the British Museum mounted their exhibition, Fake? The Art of Deception, which provided a comprehensive history of forgery beginning in ancient Egypt. Other exhibits have focused on specific issues, such as what is a fake, the art and craft of faking, the scientific detection of forgeries, and collections of known forgeries.

Our continuing fascination focuses more now on the psychology of the forger, and their motivation to forge. We ask why did someone exhaust so much energy and time creating artistic beauty, as in the case of the Spanish Forger, to copy others’ works fraudulently? Was money or fame the motive? Mark Jones (Why Fakes? in Fake? The Art of Deception, 1990), goes perhaps to the truth of the matter: Their value is in the study of our species and especially our weaknesses. They serve as keys to the changing nature of our vision and understanding of the past. Forgeries are catalysts for new scholarly analysis and scientific techniques, if not also as entertaining monuments to the wayward talents of gifted villains.

Thomas James Wise, The Forger

Wise (1859-1937) built a reputation over forty years as one of the most renown bibliographers and collectors of his time. He made a reputation in the activities of the Shelley and Browning societies. He served as the president of the Bibliographical Society, was honorary member of the Master of Arts of Oxford University, and an active member of the prestigious and exclusive Roxburghe Club of book collectors.

Thomas J. Wise. Wikipedia.

He was born in Gravesend, near London, in 1859. His father was at different times, a builder, a tobacconist, a merchant, and died in 1902. Little is known about his education, though he claimed to be educated at the City of London School, there’s no evidence of it. At sixteen, he acquired a clerk position at H. Rubeck & Co., an essential oils distributor, and moved up the ranks to become its most accomplished buyer. In 1906, he co-founded another essential oils company, which became quite successful in WWI, and it made him financially comfortable.

His book buying and selling, during this time, also brought him financial success. He was a keen collector of first editions in original condition. His interests were poetry followed by drama and his collection dating back to Elizabethan publications was an exhaustive representation. His collection was funded by selling duplicates and acting as an agent for wealthy collectors such as the Chicago millionaire, John Henry Wrenn, as well other lesser-known collectors such as the author Richard Curle, and the American collector, William Harris Arnold.

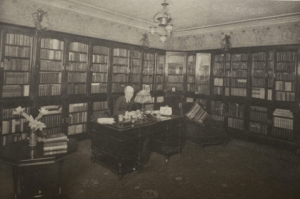

Wise in his “Ashley Library”. The Ashley library: a catalogue of printed books, manuscripts and autograph letters. (London: Printed for private circulation only, 1922-1936).

Wise’s published works included detailed bibliographies of Alfred Tennyson, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Walter Savage Landor, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Ruskin, Elizabeth and Robert Browning, the Brontë sisters, Mary and Percy Shelley and Joseph Conrad. Through his close friendship with Swinburne, he was the copyright owner and co-editor of the Bonchurch edition of Swinburne’s works. By all accounts, he was a rare book man, a collector’s collector. He socialized in the choicest literary circles and in his home library “Ashley Library” he had amassed the finest collection of rare modern books and manuscripts then in private hands in England. He allowed use of his library and built many friendships which added to his credibility as the guru of book collecting.

Carter and Pollard, The Book Detectives

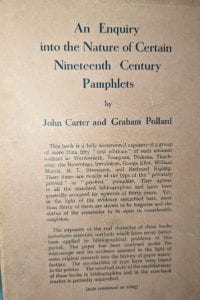

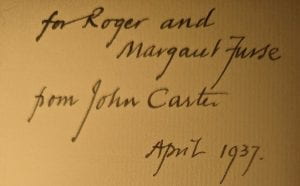

In 1934, an engaging and shocking nonfiction detective story was published with the unpretentious title, An Enquiry Into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth Century Pamphlets. Two young literary scholars, John Carter and Graham Pollard, laid out in great detail that more than fifty pamphlets by fifteen Victorian literary figures were not genuine, namely, the first issuance in print, or the first separate printing, of a particular poem, short piece of prose work, or a dramatic work.

British and American collectors had sought out such pamphlets for their scholarly, aesthetic, sentimental, and monetary value. A desire to collect early editions of the books of popular modern authors who had given their personal attention to the printing and presentation grew rapidly during the last decade of the nineteenth century. Many of these works acquired a monetary value that was higher than that of later editions which contained corrected texts.

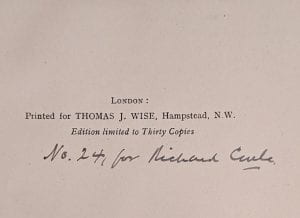

The pamphlets in question were considered rare due to the limited number said to have been produced, usually for the author (for example, Browning, Tennyson, Swinburne, Ruskin, or Rudyard Kipling) to distribute to friends before formal publication. Carter and Pollard found it odd that:

- None of the pamphlets bore any inscription from the author, especially as they were produced as gifts for specific people.

- Every copy was in mint condition showing no wear from normal usage.

- None had the signature of the previous owner.

- Not a single copy was put on sale before the 1890s even though the oldest of the items had supposedly been printed in the 1840s.

- With a claimed limited distribution of twenty-five copies, many more copies survived beyond usual expectations.

- There was no evidence of prior ownerships except that coming from the seller of the items.

- Study of the type face and paper provided reliable evidence that they had not existed before 1880.

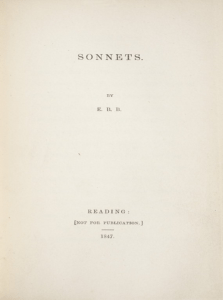

- Many had incorrect or improbable publication information, such as the Reading 1847 Browning pamphlet which had been printed by Richard Clay and Sons, of London, not Reading.

Of those questionable pamphlets, the most prized at the time was “Sonnets by E.B.B.” later to be known as Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese. The title information cites that it had been printed in Reading in 1847, for private circulation. Copies were selling for an incredible amount far above the norm for the time. In their study of this pamphlet, Carter and Pollard developed techniques of bibliographical detection and forensics which formed a new school of critical bibliography used to this day.

Wise forgery of Sonnets by E. B. Browning. The University of Chicago Library. https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/poetic-associations-nineteenth-century-english-poetry-collection-dr-gerald-n-wachs/wise-forgeries/

The owner and seller of these pamphlets was none other than Thomas James Wise. All evidence pointed to him as the forger. Controversy and debate erupted upon the publication of Carter and Pollard’s book. Some likened the reaction to the failure of a nation’s largest bank and the subsequent run by depositors thereafter unsettling the entire banking system. Many came to Wise’s defense, especially at Oxford, with whom he had close friendships. The reason why he ventured down this path of fraud remains a mystery. Some speculate it was caused perhaps by an impoverished childhood, others think it was a means to build his stature, while others saw it as a form of greed to fulfill an insatiable bibliomania. Whatever the motivations may have been, Wise denied any wrong-doing and took the truth of his villainy to the grave.

Wise Forgeries at UO Special Collections

Many collectors had been hoodwinked by Wise. The most famous being the Chicago millionaire, John Henry Wrenn, whose library was donated to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin. Wrenn had built a drama collection and Wise had helped with supplying these volumes, and with later purchases of literary works, like those by the Brownings. The bulk of Wise’s personal papers, consisting of thirty-three containers, were later purposely acquired by the Ransom Center. In her sleuthing, the curator of the Wrenn collection, Fannie Ratchford, also uncovered many items stolen by Wise from the British Library.

The UO Special Collections holds many of Wise’s scholarly publications and at least three suspected forgeries.

Robert Browning. Gold Hair: A Legend of Pornic. (London: Printed by W. Clowes and Sons, Stamford Street and Charing Cross, 1864).

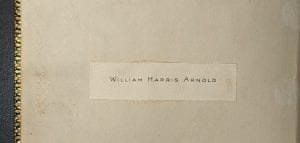

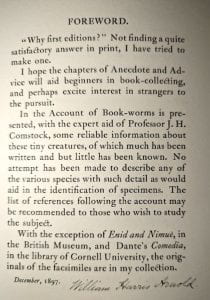

This title is cited by Carter and Pollard in their Enquiry (p. 181-182). William Harris Arnold (1854-1923) was its previous owner. The UO Library purchased the item in 1958. The small pamphlet was bound by Zaehnsdorf, the renowned English bookbinder, in a blue-green Moroccan leather with gold-gilt interior boards and marbled paper. The binder’s “exhibit” seal is embossed on the interior end board.

Little is known about Arnold except for his many publications about collecting first editions and his personal library collection, as well as sales catalogs of his books. In his Ventures of Book Collecting (), he cites his ownership of Gold Hair. He further elaborates on one source of his collecting: “Through the kind offices of my new, but now dear old, friend the distinguished collector and bibliographer, Mr. Thomas J. Wise, I obtained one Tennyson rarity after another, most of which were at that time unknown to American collectors” (ibid, p. 14). Arnold sold a cache of his books before his death and his widow sold the remainder at a New York auction sale in 1924. In Ventures, he bragged about the return on his investments not knowing that he had been suckered by Wise.

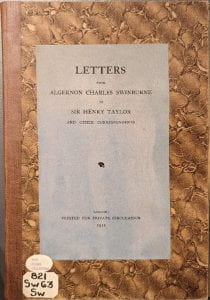

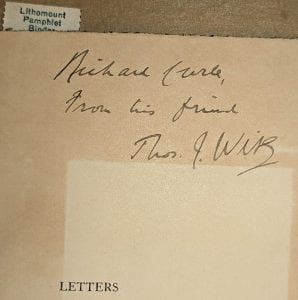

Letters from Algernon Charles Swinburne to Sir Henry Taylor and other Correspondents. (London: Printed for Thomas J. Wise, Hampstead, N.W., Edition limited to Twenty Copies, 1912).

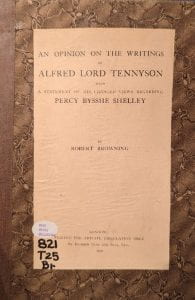

Robert Browning. An opinion of the writings of Alfred Lord Tennyson with a Statement of his views regarding Percy Bysshe Shelley. (London: Printed for Private Circulation Only by Richard Clay and Sons, 1920).

Both titles were acquired from Wise by Richard Curle, who donated them to the University of Oregon Library in March 1948. It is not known why Curle donated his Wise copies to UO Library. Both pamphlets were rebound by the UO Library in library pamphlet binders at which time the original covers were cut and pasted to new boards. It is unknown what other provenance information may have been lost by rebinding but the chain of custody is clear, nonetheless.

Richard Curle (1883-1968) was born in Scotland. After leaving Wellington College in 1901, Curle established himself as a journalist and writer in London. In his early career, he wrote leaders for such newspapers as the Pretoria News (South Africa), The Rangoon Times (Burma), and The Daily Mail (England). He also wrote articles for other newspapers and magazines, short stories, and books of fiction and non-fiction. In 1912, Curle was introduced to Joseph Conrad and, because of their long-standing friendship, much of Curle’s writings and correspondence with colleagues and friends reflects his considerable knowledge of Conrad and his works. He too had a keen interest in first editions as evidenced by his book: Collecting American first editions: its pitfalls and its pleasures (1930). It is most likely through this shared interest in Conrad and first editions that Wise and Curle became friends.

References

Altick, Richard D. The Scholar Adventurers. (NY: The Free Press, 1966).

Arnold, William Harris. Books and Letters. (Jamaica, New York: Marion Press, 1901).

Arnold, William Harris. First Report of a Book Collector. (Jamaica, NY: Marion Press, 1898).

Arnold, William Harris. Ventures in Book Collecting. (New York, London: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1923).

Carter, John and Pollard, Graham. An Enquiry into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth Century Pamphlets. (London: Constable & Co.; NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934).

“Creative Forgeries: Thomas J. Wise and His Fictitious Imprints.” University of Delaware Special Collections & Museums. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/things-arent-what-they-seem/home/creative-forgeries-thomas-j-wise-and-his-fictitious-imprints/

Curle, Richard. Collecting American First Editions: Its Pitfalls and Its Pleasures. (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1930).

MacDonald, Dwight. “Annals of Crime: The First Editions of T.J. Wise”, New Yorker Magazine, November 10, 1962.

“The Nineteenth-Century English Poetry Collection of Dr. Gerald N. Wachs.” University of Chicago Library. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/poetic-associations-nineteenth-century-english-poetry-collection-dr-gerald-n-wachs/wise-forgeries/

“Thomas James Wise: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center.” Harry Ransom Center. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://norman.hrc.utexas.edu/fasearch/findingAid.cfm?eadid=00914

Voelkle, William M. Holy. Hoaxes: A Beautiful Deception, Celebrating William M. Voelkle’s Collecting. (NY: Les Enluminures, 2022).

Works written by or edited by Thomas J. Wise in the UO Library.

— David de Lorenzo, Giustina Director