Time seems to slow as the soil liquefies, bridges collapse and buildings collapse

The BBC video “The Next Megaquake” dramatizes how devastating the earthquake could be for the Northwest. The segment beginning at the 37-minute mark is especially compelling.Yumei Wang vividly remembers being in a lighting store in California during an earthquake. The ceiling was covered with chandeliers and other lighting fixtures. “The shaking made the whole ceiling sway,” she says.

And though it was only seconds, Wang, who is now the earthquake risk engineer for the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, described the experience as interminable.

A feeling of time slowing, hyper awareness and vivid, detailed memories — sometimes called flashbulb memory — is common for people who experience earthquakes.

Most earthquakes in recent memory on the West Coast have lasted seconds to a few minutes, but the predicted 9.0 Cascadia earthquake event is expected to rock 600 miles from California to Canada for three to five minutes. Wang says that, like rings from a pebble thrown in a pond, the seismic waves from an earthquake emanate outward three-dimensionally, and scientists estimate that very strong shaking and damage from the Cascadia quake will reach 100 miles inland, essentially to the Cascade Range.

Survivor Memories

Here’s what survivor memories might capture during those initial minutes.

It may not immediately appear to be an earthquake. People on the coast nearer the epicenter may feel like they were in a building just hit by a truck and will have a hard time just standing upright. People who are farther away from the coast may find themselves walking like they’re drunk. Water-saturated, sandy soil may liquefy during the shaking and temporarily become quicksand.

“It’s not like the Tarzan movie. Things won’t disappear, but they will sink a few feet,” Wang says.

Depending on how close they are to the coast, people who are driving and already in motion may not notice the shaking ground. Violently swaying power lines may be their first clue. Roads and bridges will be damaged. Many bridges across the state will collapse.

Earthquakes don’t necessarily make noise, but buildings will creak and groan with the shaking. Household items such as refrigerators and desks may move across the room, shelves may topple, dishes and wall hangings may fall. Windows, chimneys and architectural decorations could topple off buildings.

“That’s why it’s important to not run out of buildings, but duck, cover and hold,” Wang says, adding that you should orient your face away from windows, which can fall and break into the building.

Infrastructure that communities rely on will also be affected, and most basic services will be severely disrupted. “Waste water and water systems always get hammered in earthquakes,” Wang says. Water pipes can burst or crack; plumbing and wiring for electricity and gas will likely be down too.

Small, wood-frame buildings and homes have enough flexibility that most of them will survive the quake. But houses not anchored to their foundations may slide off, breaking water, sewer and gas connections. One of the bigger worries with wood homes is fire. Firefighters may not be able to reach the home in time, and even if they come, the water may not.

Old masonry buildings, like many historic government buildings and schools, often weren’t built or updated with adequate reinforcement. These can collapse within seconds of the shaking, Wang says.

“I’ve been to many earthquakes. It’s stressful and sad when basic services are out,” Wang says. “But it’s worse when there have been mass casualties of students in a school.”

Months, even years later basic systems could still be down.

Months, even years later basic systems could still be down.

Those first months afterwards will be a challenging time for the Northwest, says Wang.

“The shaking will probably be something people never forget, but water and warmth will be major concerns afterwards,” she says. Often, earthquake survivors feel like the ones who died were lucky.

If an earthquake were to hit our region tomorrow, next month or even next year, Oregonians’ basic services would be down for a long time.

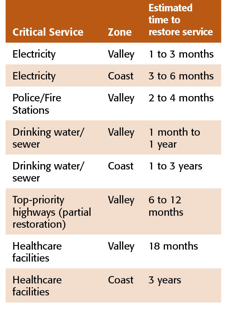

Estimates range from one month to a year, and up to three years along the coast, for water systems to regain functionality, according to The Oregon Resilience Plan. Electricity could be down for one to three months in the valley, but on the coast, it could take up to six months to get back to normal. Healthcare facilities at the coast could take as long as three years to restore.

“The good news is that most people won’t die, and the other part of the good news is that we haven’t been hit yet. So preparing is a smart option,” Wang says.

Earthquake experts like Wang are beginning to see politicians and the public take notice of their research and warnings. Things are starting to happen: The Governor’s Oregon Resilience Task Force is looking at The Oregon Resilience Plan to determine which preparations should happen and in what order.

Private citizens can help, too, by having emergency supplies and plans in place for their own families, and by demanding their public utilities are prepared.

Oregon can leverage this threat into a culture of readiness. “We can do a lot to reduce the damage … it can be like saving for retirement,” Wang says. “Planning for these kinds of things that are eventualities is especially important sooner rather than later.”

Article reprinted with permission from Community Vitality Publication, Spring 2014, © 2014 The Ford Family Foundation. For the full Community Vitality edition of ”The Time to Prepare”, visit http://www.community-vitality.org/Spring2014TimeToPrepare.html