by Riki Saltzman, Folklore Specialist, OFN and Folklorist, High Desert Museum

During this pandemic year, I’ve had the privilege of doing folklife fieldwork for two projects—OFN’s statewide folklife survey, taking place this year on Oregon’s southern coast, and the High Desert Museum’s central and eastern Oregon folklife documentation project. It’s been rather amazing to flit back and forth across two mountain ranges and travel along the coast, through the high desert, on ranchland, and on the sovereign lands of four federally recognized Tribes—particularly since it’s all been virtual, taking place on the phone, and over Zoom.

Normally, ethnographic fieldwork involves driving—lots of driving—to meet up with culture keepers around the state who so graciously and generously share their cultural traditions with me. With my camera and my audio recorder, I’d spend several hours documenting and asking questions—lots of questions—before saying my goodbyes and heading off to the next scheduled interview. Back home or in my hotel room, I’d identify photos, create audio logs, and write up fieldnotes to record the day’s observations—all of which becomes metadata for OFN’s archives in the University of Oregon Libraries Special Collections.

But this year, so much is different. While I’ve started out with emails and phone calls to those I know in both regions, I’m restricted to Zoom for interviews—and in some cases recorded phone calls for those without sufficient internet access. While Zooming has brought its share of glitches, fits and starts, and technical challenges, the platform does make it possible to meet new people, find out about their cultural traditions and artistry, and get to know them better. A pre-interview phone call with the folk artist helps us figure out together what aspects of their cultural traditions to focus on. I’ve found that asking people to describe the processes of how they do what they do, especially when I’m not there in person to observe and document for myself, enables me (and future researchers) to “see” their process. For food preparation, that might include the steps involved in cooking, preserving, or baking. For traditional crafts, we’d explore the gathering and preparation of materials as well as how to make a traditional item like a Klamath Tribes’ tule duck decoy. For storytelling or cowboy poetry, we might discuss what makes a good story or poem, who taught the artists, when and why they tell certain stories, and to whom they tell them.

Oregon’s Southern Coast

For OFN’s south coast survey, I started out looking at the County and Tribal Community Cultural Plans for Coos and Curry counties, the Coquille Indian Tribe, and the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians. A press release announced the start of the project, detailed the kinds of traditions we were wanting to document, and enabled me to find contacts for culture keepers from the region. I also wrote many emails—to those I already knew in the region and to those others had recommended. While work in the region will continue through June 2021, we now have some brief snapshots from culture keepers who have shared their traditions:

Don Ivy, Chief, Coquille Tribe, is a fisherman’s fisherman and the possessor of a wealth of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) that he shares generously. Ivy grew up fishing in the waters of Coos Bay, along the estuaries, and in the Pacific. “My relation to the natural world is always in the context of water—where is it and what’s in it,” he said.

But Ivy didn’t know that what he and his cousins were doing as children was traditional. “I cannot remember a time in my growing up days when I didn’t have a fishing pole—a stick…plunking around in a crick or lake or off the dock in Charleston. I never was not around people who fished.” His mother and her sisters, who grew up in Charleston, worked on the dock and picked crab and shrimp; her father and brothers were fishermen. He recalls, “Everyone fished—catching crabs or digging clams. It was part of the routine of life. If you didn’t fish, someone who’d been fishing came by and shared food.”

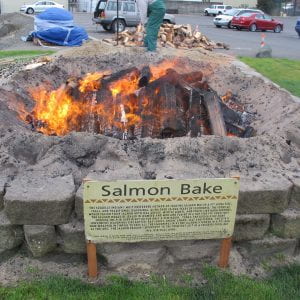

The turning point for Ivy came when his mother told him to come home from Portland, where he was working, to prepare the salmon bake for the Coquille Indian Tribe’s first Restoration Day powwow in 1989. The event involved not just eating but cultural sustenance, the very essence of potlatch, as Ivy and others wove the traditional knowledge from ancestors—the year’s round of fishing, different fishing techniques for different fish, cooking technologies, and then serving the traditional food (first to elders)—to honor the day and federal recognition of the Coquille Tribe’s sovereignty. Ivy recalled how he met many cousins and others from this large extended family as his elders guided him in preparing traditional foods in traditional ways.

Reflecting upon his childhood, Ivy explained that he could recognize parts of traditional culture that weren’t identified as Indian at the time. For instance, “the places we went for picnics were important places in the history of the Coquille people: Whisky Run, South Slough…we went back to places important to previous generations.”

Ivy, who has done extensive archeological research over the years, has partnered with Oregon’s Department of Fish and Wildlife and others both to restore traditional knowledge and use it to restore balance to Oregon’s waterways and wetlands, in particular the Coos and Coquille river systems. Traditional foods and lifeways—including lamprey habitat, basket making (gathering, processing, weaving), and, as Don Ivy puts it, “the fundamentals of safety, shelter, sustenance”—are key aspects of that knowledge. The trick, he said, is to combine the archeological record with the storytelling that is part of every family’s tradition—”those family experiences, the little glimpses from some elder that resonated and got retold.”

Stacy Rose, South Coast Folk Society, is a traditional Jewish cook and baker, Israeli folk dance teacher, and musician based in North Bend. Rose, who grew up in Philadelphia, is the child of first-generation American parents raised in Eastern European Orthodox Jewish families. She came to Oregon to visit her sister in the early 1980s and stayed. Her Jewishness is part and parcel of her ethos, and she joyously shares her knowledge of traditional dance with her congregation and the greater south coast community. A traditional and innovative cook, she is known for her bagel brigade and matzah ball soup, which she delivers to those who need their comfort and sustenance.

Sharing is at the center of who Stacy Rose is and what she does. When she first came to Oregon, she and friends started the South Coast Folk Society. “Out of that we started doing community dance, including Israeli folk dancing. From there, it was easy to make the transition of sharing that passion for Israeli folk dancing with Congregation Mayim Shalom…We always have live music and dancing, and it’s just a part of who we are…It’s great to join hands in a circle with your friends and feel that energy and share that connection. When we get out there and people hear the music and some of them have this ‘oh, I remember when we used to do this’ and it brings back and they join the circle. It touches an old place and…it just triggers something.”

Jewish food traditions also touch people in a deep way. Rose, whose maternal grandmother emigrated from Lithuania, recalls that her first memory of Jewish food goes back to her childhood in the Philadelphia area. “[M]y bubbe [grandmother] would come from Chicago…with a suitcase filled with ingredients…. And I remember walking home from elementary school and opening the door just a crack and smelling the cooking. Smelling her food…meant she was there.”

Rose especially remembers her grandmother’s borscht (beet soup) and matzah brei (fried matzah and eggs). “The only time we ever had borscht was when bubbe came. One thing that she always made for breakfast was fried matzah…And I like to make fried matzah for my grandsons. I never make it for myself, but I always make it for them. And they have been a part of that, making it, too, so that the two older ones know how to make it now.”

“I [also] like to make matzah ball soup. I find comfort in that. I tell people it really does heal, it’s a healing bowl, a bowl of health.” But not everyone understood the particularities of this traditional Jewish remedy, and Rose was surprised to find that the first time she made the soup for an ill friend, that the person (not Jewish) assumed that the soup contained only plain broth and matzah balls because “she doesn’t have money to put anything in the soup, you know, to buy ingredients…So that was an interesting eye opening experience…other people in other traditions are not expecting [such a plain soup, but] …That’s soup. So, I do like to share matzah ball soup because I believe in it.”

She also likes to make bagels, partly because “people love bagels. And it’s hard to find a good bagel.” Living where she does, Rose explains, “my bagels are good, just like my playing music is good because I live in a small town. So, you know, being a big fish in a small pond has its advantages. But I do like to make bagels for people because it makes people happy.”

These are just two of several people who’ve been generous enough to respond to my emails and messages during this leg of the survey. Both Don Ivy and Stacy Rose also referred me to other culture keepers in the region, which is the way that fieldwork works. I’m in the process of doing interviews with those folks and lining up more. Look for updates about Oregon’s coast in future newsletters!

Folklife fieldwork at OFN is funded with grants from the National Endowment for the Arts Folk & Traditional Arts Program.