MOCCA identifies students who are and are not comprehending well. When students are not comprehending well, MOCCA offers diagnostic information that can inform instruction. MOCCA categorizes comprehenders into four types, and for college students also offers information regarding comprehension efficiency. This guide helps you understand the scores that MOCCA provides, as well as their implications for instruction. The topics covered are:

- MOCCA Scaled Scores

- Percentile Ranks

- MOCCA Comprehender Types

- Comprehension Efficiency (applies to College MOCCA only)

MOCCA Scaled Scores

The MOCCA Scale Score reports a student’s reading comprehension performance on a scale from 50 to 950, where 500 is the average score and 150 is the standard deviation. This scale looks similar for all grades and college students, but their interpretation is slightly different depending on whether a student is in Grades 3 to 6 or in college.

Grade 3 to 6 Scaled Scores

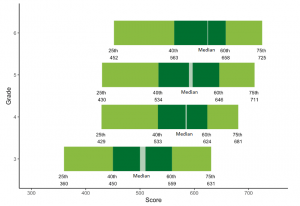

The MOCCA Scaled Score can be used in Grades 3 to 6 to track student improvement in reading comprehension from the beginning of Grade 3 through the end of Grade 6. Students who are making progress in reading comprehension should have scores that increase across Grades 3 to 6 because the range of typical performance increases across these grades. In the figure below, you can see how the range of typical scores changes from grade to grade. The median, or average, performance is depicted with a very light green band, while the scores for the the next 10% of students in either direction is in dark green and an additional 15% are in light green. The full length of each bar represents how the middle 50% of students perform at a given grade level. As the figure makes clear, scores shift up on the MOCCA scale across Grades 3 to 6. The shift is larger between third and fourth grade, than across the subsequent grades.

MOCCA Scaled Score Ranges by Grade

College Scaled Scores

College Scaled Scores work much the same way as in Grades 3 to 6, but the comparison group is different. The comparison group for College MOCCA is college students. Because the comparison group does not change, the College scale median, or average, is always at 500.

Percentile Ranks

Percentile ranks convey the percentage of students that a student performed as well as, or better than. This score can be used to understand how a student is performing relative to similar students in the same grade. A percentile rank of 50 means a student scored as well as or better than 50% of students at their grade level (see figure below).

Students at the 50th Percentile Rank Performs as well as or better than 50% of Their Peers

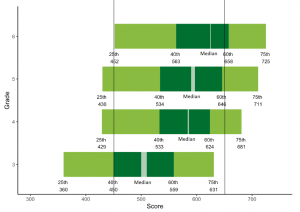

Because MOCCA scaled scores are on a continuous scale across Grades 3 to 6 and percentile ranks are based on grade level, the same scaled score will result in different percentile ranks depending on a student’s grade (i.e., the grade level to which they are compared). For example, a scaled score of 650 is the 81st percentile rank in Grade 3, the 68th in Grade 4, the 61st in Grade 5, and the 58th in Grade 6. Similarly, a scaled score of 450 is the 40th percentile rank in Grade 3, the 27th in Grades 4, the 26th in Grade 5, and the 24th in Grade 6. This effect is also visible in the figure below.

Percentiles by Grade for MOCCA Scaled Scores of 450 and 650

Percentile ranks are not always as meaningful as they appear. In particular, teachers should pay attention to the grade level of the form of MOCCA a specific student has taken and whether a student has finished the full assessment.

Percentiles are only meaningful when students take MOCCA for the same grade level in which they are enrolled. If a student takes MOCCA off-grade, the percentile rank compares that student to students in their grade who took a same-grade form, which is not a valid comparison.

If a student does not complete MOCCA, percentile ranks need to be interpreted with great caution. The fewer items a student has completed, the less reliable their score. You can confirm that a student completed the full assessment by checking their status on the MOCCA roster screen, where their status will read “Not started,” “Incomplete,” or “Complete.” Unless a student’s status reads Complete, the percentile rank should be interpreted with caution.

MOCCA Comprehender Types

To understand MOCCA Comprehender Classifications, you need to understand causal inferences. If you already know what a causal inference is, you can skip to the Comprehender Type you’re interested in. Otherwise, read on!

What is a causal inference?

Causal inferences are inferences that are required for a text to make sense. They are sometimes called necessary inferences. The following very short story serves as a great example.

Tyrese decided to bake a pumpkin pie for dessert. He looked in the pantry. Tyrese was disappointed.

In this story, one can infer that Tyrese did not find all the needed ingredients in the pantry. Most proficient readers will immediately and effortlessly infer that. In fact, they also infer that Tyrese must think the ingredients will be in the pantry.

Proficient readers may be entirely unaware that they have made those two necessary inferences. What makes them necessary is that the three sentences become non sequiturs without those two inferences.

There are other “unnecessary” inferences that readers can make as well. One might infer what Tyrese’s gender, what Tyrese looked like, and even what specific ingredients were missing or the type of dish the pie might be baked in. While all of these inferences elaborate and enrich, or flesh out, the story, making it more interesting and complete, they are not necessary to understanding the central core of the text. Thus, they would not be considered causal inferences.

Where did the comprehender types come from?

The MOCCA comprehender types are based on reading research conducted with a method called a “think aloud.” Think alouds have been used in instruction for many years now, but before that, they were primarily a means of understanding what readers were thinking while they read. The method has also been used in many kinds of psychology studies, in marketing research, and many other kinds of studies. In reading, researchers ask readers to stop now and then — for example, after every sentence, paragraph, or page — while reading to say what they are thinking aloud.

Think aloud research in reading has taught us much of what we know about reading comprehension. It is how we first identified the cognitive strategies that proficient readers use to understand what they read and the source of the comprehension strategies we teach our students. Although the list of strategies we teach may vary based on the curriculum we use, two of the most common strategies are paraphrasing and making inferences, especially elaborative inferences. It turns out that readers who are struggling specifically with comprehension (but not word reading) tend to rely on one or the other of these strategies a lot. MOCCA helps to identify whether a reader is “stuck” on using one of these two strategies, which gives teachers the information they need to get them “unstuck” and making progress in comprehension.

Read on to learn more about each comprehender types and the instruction that helps them best. Or jump to the comprehender type you’re most interested: Causal Comprehender, Elaborating Comprehender, Paraphrasing Comprehender, and Inconclusive Comprehender.

Causal Comprehenders

Causal Comprehenders regularly make the causal inferences necessary for comprehension. Causal Comprehenders do not require help making these inferences.

They will benefit from continuing to read texts they enjoy and find challenging. Like all readers, they also benefit from talking to others and writing about what they have read. These practices will help them maintain and grow their comprehension of and engagement with texts.

Paraphrasing Comprehenders

Paraphrasing Comprehenders do not regularly make the causal inferences necessary for comprehension. Instead, Paraphrasing Comprehenders tend to paraphrase or repeat what they have read, sticking to a relatively literal interpretation of texts.

To improve their comprehension, these readers will benefit from being prompted to make various kinds of inferences. These inferences can connect ideas from different places in a text (often called bridging, connecting, or text-to-text inferences). They can also use a reader’s background knowledge (often called elaborative, text-to-self, or gap-filling inferences). All inferences require a reader to supply information that is not explicitly stated in a text, which is what helps deepen comprehension.

We recommend explicit instruction in making inferences, where the teacher models inferences and engages students in group and individual practice at making inferences. Here is an example of defining and modeling a bridging (also known as connecting or text-to-text) inference:

We know [state an event or fact from the text] happened, and we know [state another event or fact from the text] happened. When we connect these ideas, we can infer [a detail that is not explicitly statement].

You can also use questioning to prompt Paraphrasing Comprehenders to make inferences when reading. These questions work in whole class, small group, and individual settings. Here are two questions that specifically prompt connecting inferences:

How does what we just read connect to what we read earlier?

How does what we just read connect to [state an earlier important idea from the text]?

Here are two questions that specifically prompt elaborative inferences (including a predictive inference):

What do we already know about [state main topic from the text]? How does that connect to what we just read?

What do you think will happen next? What clues in the text make you think that?

Elaborating Comprehenders

Elaborating Comprehenders do not regularly make the causal inferences necessary for comprehension. Elaborating Comprehenders do make inferences about information not explicitly stated in a text, but that information is not strictly needed to comprehend a text. These inferences are nice to make and may enrich the reading experience, but they do not provide information that is necessary for comprehension.

To improve their comprehension, these readers will benefit from being prompted to make causal (i.e., necessary) inferences. These inferences use a reader’s background knowledge to fill in important information that is not explicitly stated in a text. Causal inferences tend to focus on why events occur as they do or characters behave as they do.

We recommend explicit instruction in making causal inferences, where the teacher models inferences and engages students in group and individual practice at making causal inferences. Here is an example of defining and modeling a causal inference:

We know [state a goal or problem from the text], and we know [state an event or behavior from the text] happened. When we connect these ideas, we can infer that [the event/behavior] happened because [restate the goal or problem].

You can also use questioning to prompt Elaborating Comprehenders to make causal inferences when reading. These questions work in whole class, small group, and individual settings. Here are some questions that specifically prompt causal inferences:

Why do you think that just happened? What clues in the text make you think that?

Why do you think that character did that? What clues in the text make you think that?

Why do you think that character said that? What clues in the text make you think that?

Why do you think that character wants that? What clues in the text make you think that?

Inconclusive Comprehenders

Inconclusive Comprehenders do not regularly make the causal inferences necessary for comprehension. Inconclusive Comprehenders do not demonstrate a reliable pattern in what they do when they do not make causal inferences. There are a number of reasons a reader may end up classified as inconclusive.

Some Inconclusive Comprehenders may be struggling with lower level reading skills, such as reading words and fluency. If you have data from other assessments that suggests a reader is struggling with lower level skills, we recommend focusing intervention on those skills. In the meantime, it may help to offer the student easier to read texts that allow them to practice and enjoy reading for comprehension. Audio books at grade level can also be an important way to give the student access to rich, grade-level content while they work on their skills.

Inconclusive Comprehenders who demonstrate strong lower level reading skills on other assessments may be struggling with literal comprehension, especially if other assessments also indicate a comprehension problem. In some cases, the student may not be prioritizing reading for meaning, which can occur when instruction is overly focused on lower level reading skills. Difficulties with literal comprehension are best addressed through engaging students in active reading practices. Having the student read aloud and stop to discuss what they are reading. Occasionally asking literal (i.e., Who? What? When? Where?) and inferential questions about a text will help the reader focus on meaning while reading. See the suggestions under Paraphrasing and Elaborating Readers for information on how to encourage inference making.

Other Inconclusive Comprehenders may be guessing when they take MOCCA. If you feel a student may have been guessing or otherwise disengaged while taking MOCCA, you may wish to reassess after encouraging the student to take their time and do their best work.

Otherwise, these readers will benefit from continuing to read texts they enjoy and find challenging. Like all readers, they also benefit from talking to others and writing about what they have read. These practices will help them maintain and grow their comprehension of and engagement with texts.

Comprehension Efficiency

Comprehension efficiency information is only offered for the College version of MOCCA. Indicators of comprehension efficiency should not be taken to mean that faster is always better. The main goal is for all students to be accurate in their comprehension. A fast indication is only good insofar as a student is comprehending (i.e., is fast and accurate). Note that accuracy here relates not to decoding, but to a student’s ability to resolve causal gaps in a narrative by making a causally coherent inference.

Students who are fast and inaccurate likely need to slow down. They may be students who rushed through the test either without really reading or without really trying to do well. However, they may also be students who when they read are prioritizing speed over accuracy in decoding or prioritizing fluency over meaning. Other data is necessary to determine their needs.

Students who are slow and accurate comprehend well. They may need to work on fluency in order to improve their reading pace. They may also need to work on decoding if they perform better on measures of word list reading than passage reading. Other data is necessary to determine their needs. However, for students with IEPs or receiving English language services where additional time is a recommended accommodation, this designation may be reiterating the need for that accommodation.

Students who are slow and inaccurate do not comprehend well and proceed at a slow pace. Depending on their comprehension rate (also found on MOCCA reports), they may just be a bit slow or very slow. A number of issues may be underlying their performance, including but not limited to poor decoding and/or fluency. Other data is necessary to determine their needs.

Always be sure to coordinate MOCCA results with other data sources. Only students who get at least one item correct receive a comprehension efficiency indicator.