Digital Maps and Relative Elevations

A Relative Elevation Map (REM) of Shaver’s Fork, WV

I have spent many years on mapping projects starting from my early days back in 1992 working on maps for The Nature Conservancy. I started at the National Zoological Park’s research labs in Front Royal Virginia. Back then, I was just a grunt digitizing maps of the Smoke Hole Region of West Virginia, an area full of rare flora and fauna. I was such a grunt that I would drive 100 miles each way to spend a day being a grunt to just learn how to map. Doug Muchoney was my mentor and he was willing to teach. Flashing ahead two decades, I am still quite involved in mapping projects even to the point of teaching classes in the Earth Science Department for a field methods class.

Our Geography Department teaches basic GIS classes but not ones fully geared toward geologists and the folks in the Earth Sciences Department wanted something a bit more focused on geologic mapping. We also focused on using the opensource QGIS program and not esri’s ArGIS. QGIS is often considered to be more friendly for people working in the field and not always connected to the Internet. However, most municipal, state and federal agencies use esri’s products.

Our field methods class was still quite traditional. I taught students how to create and edit points, lines, and polygons, how to fill and edit attribute tables, how to align photographs, how to import digital elevation maps and LIDAR imagery, create slope, aspect, topographic maps and in particular interest, how to create relative elevation maps (REMs).

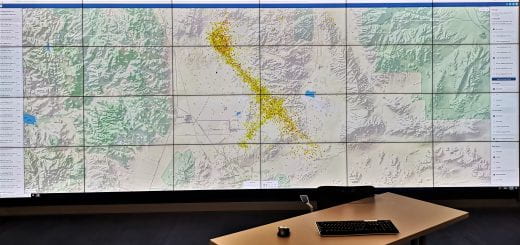

Daniel Coe, of the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, devised a nice methods of making these maps. A relative elevation map is one where a stream running through a mathematical landscape is tilted such that the high of the stream at one end of the map is the same at the height/elevation as the other end. This might happen more frequently on impounded waterway that are now reservoirs. However, in the natural world, water still flows downstream from one point to the next. In the REM, we are mathematically leveling the stream. This is mainly to look at how alluvial deposits appear on the landscape, and to infer their age, and the expected energy needed to influence terrace formation. If we stick to a traditional digital elevation map, two terraces of equal height but widely spaced along a map would likely be missed, because the starting ground level and therefore their final elevation of each would be different even if both were two meters tall. These maps are also great ways to look at the meanderings of stream across a valley floor. Dan Coe, has made his name making these maps. Here is my try, an example of REM for the Shavers Fork Area in Randolph County, West Virginia. This is where I first saw a hellbender, North America’s largest salamander, and near that original Smoke Hole area where I made my first digital maps.